In her search for the perfect line, Susan Schwalb has brought the Renaissance art form of metalpoint into the 21st century.

Metalpoint artist Susan Schwalb uses a fork a bit differently from most people. While you or I use it to pick up a floret of broccoli or stab a piece of beef, Schwalb uses it to draw. She also uses steel wool; flat bars of silver or gold; and special styluses that hold fine pieces of silver, copper, or other metals. Basically, if it’s metal, chances are she’s tried drawing with it.

While this might sound like a strange new idea, drawing with metal—aka metalpoint—actually has a long history. In the Renaissance, long before graphite or red chalk existed, Leonardo da Vinci, Albrecht Dürer, and other Renaissance masters used metal to sketch out their ideas. The works were often unfinished, really more a means to an end than a product in itself.

Schwalb’s work, however, is anything but unfinished. This is work that is absolute and final, her intricate lines meticulously drawn, each with its own place in the abstract story she’s creating. Schwalb has taken an ancient technique and made it boldly contemporary by experimenting with different metals and evolving it from its figurative beginnings into the abstract. Her innovation and vision are recognized far and wide in the art world—her drawings and paintings can be found in the collections of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts, and London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, among many others.

Not bad for a technique Schwalb discovered by happenstance. “I was doing very precise ink drawings with a Rapidograph pen,” she recalls. “I kept looking for finer and finer lines. And then I was in the Hamptons with a few other artists for a few weeks. I looked at this artist working; it was silverpoint. Here’s a tool to make a line on my painting! I went back to the city, bought paper and tools, and started. Within a year it was my primary medium. “It’s the precise line I love. I never looked back.”

Intermezzo XXI, 2015, tin, silver, and goldpoint on black gesso, 12 × 12 × 2.125 in. Photo by Jacklyn Boylan

And yet, of course, she did look back, at least initially. Because looking back at the Renaissance is really the only way to learn how to do metalpoint. The drawings themselves are the only points of reference.

“I’m not that interested in all Renaissance drawings,” Schwalb says, “but I’m always interested in Renaissance silverpoint.” Apparently . . . how else to explain her spending not one, not two, but four days looking at the metalpoint retrospective Drawing in Silver and Gold: Leonardo to Jasper Johns at the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC in 2015? “By day two, my husband was looking at other parts of the museum, but I wasn’t. There are things in these drawings.

“I’m not looking at the whole image,” Schwalb continues. “Sometimes it’s just a little section.” She cites Rogier van der Weyden’s Portrait of an Unknown Young Woman as an example. The woman wears a traditional Dutch headdress with a flowing scarf. “I was really looking at how he got the darks and the lights,” Schwalb explains. “Right below her neck is a really thin line. I kept looking, looking, and looking.

“I found this medium, and it doesn’t seem to let me go.”

At her airy Watertown, Massachusetts, studio, Schwalb stands by her drawing table to illustrate various metals’ versatility. She picks up a piece of paper and grabs the aforementioned silver fork, pulling it across the paper to leave a line. She trades the fork for a piece of steel wool and creates a different set of lines. “You can draw with jewelry,” she says, scraping her ring against the wall to make a smudge. “It’s not complicated. What’s hard is the drawing. It is a direct medium. You have to be able to draw.”

Susan Schwalb lines up at her Watertown studio. Photo by Izzy Berdan

Each metal has its own properties, too. Understanding which one tarnishes and how much, for instance, is something Schwalb considers before she begins a piece. Silver, copper, and brass all change color differently. Tarnishing is also affected by the surface and time of year. In humid summer months, a piece can tarnish overnight. In the winter, it can take months. “I try to anticipate it, but I don’t always know,” she says. “Even after 40 years, the medium can surprise me. That’s the fun.”

Schwalb prefers to create series of drawings or paintings rather than individual works, exploring variations on a visual theme. “I do it because I want to try something else—different colors, different metals,” she explains. “One piece leads me to another.”

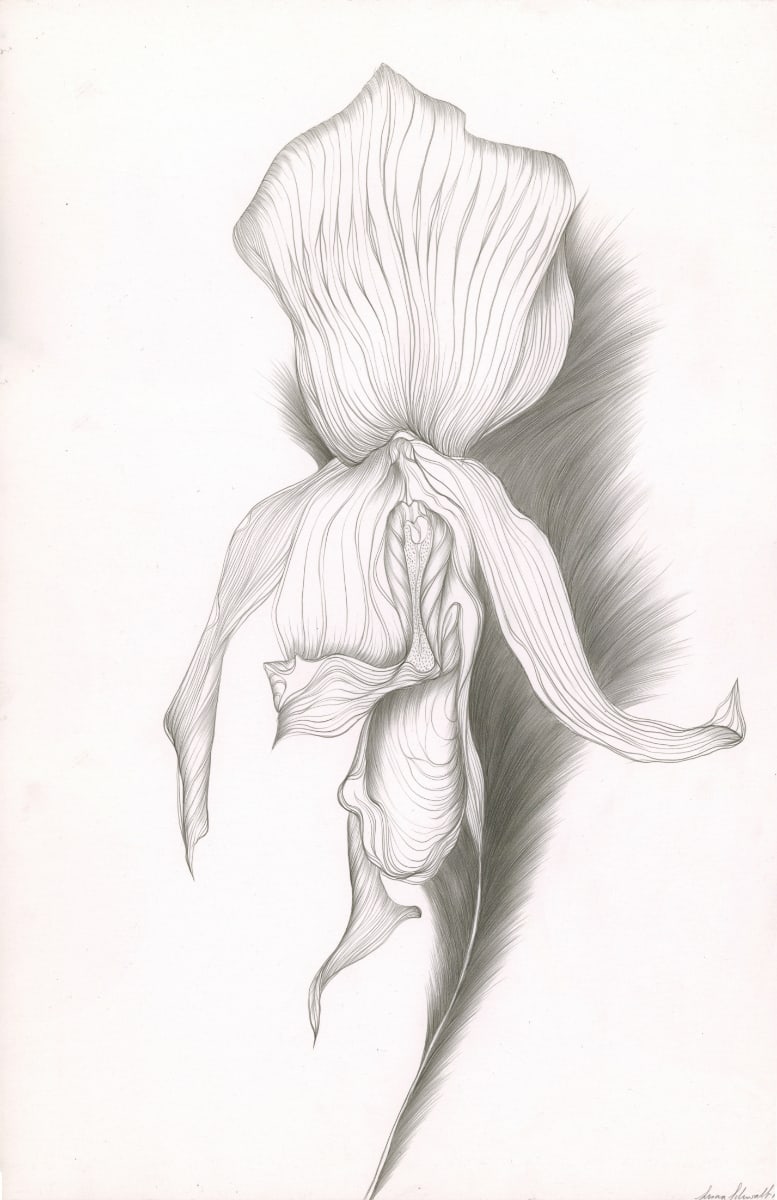

Her Orchid series, which began as a figurative study, gradually morphed into abstraction as Schwalb created lines around the orchid. “I took the image out. I was drawing what was behind it.” Then she began to tear the paper, eventually burning its edges. “I used a match, then a candle. I finally had to give up burning; if you put your finger on it, there’s a fingerprint,” she says, noting she used burning from 1978 to the early ’80s.

Through it all, she was always searching for the perfect exact line. “I have combined everything—gold leaf, tempera, burning the edges of the paper,” she says, recalling various phases. “It was that I was looking for a very fine line.”

While the colors, textures, and metals vary in her series, the linearity unites her work. Sometimes the lines are straight as arrows—she uses a T-square to ensure that. Other times they waver slightly. Sometimes she mixes the metals. Other times it’s one metal against a solid color.

Schwalb gives her series fairly generic titles—Strata, Music of Silence—deliberately. Individual paintings simply receive a number, as in Strata #246. She often uses musical references. “I don’t want a title that makes you read an image in it,” she says.

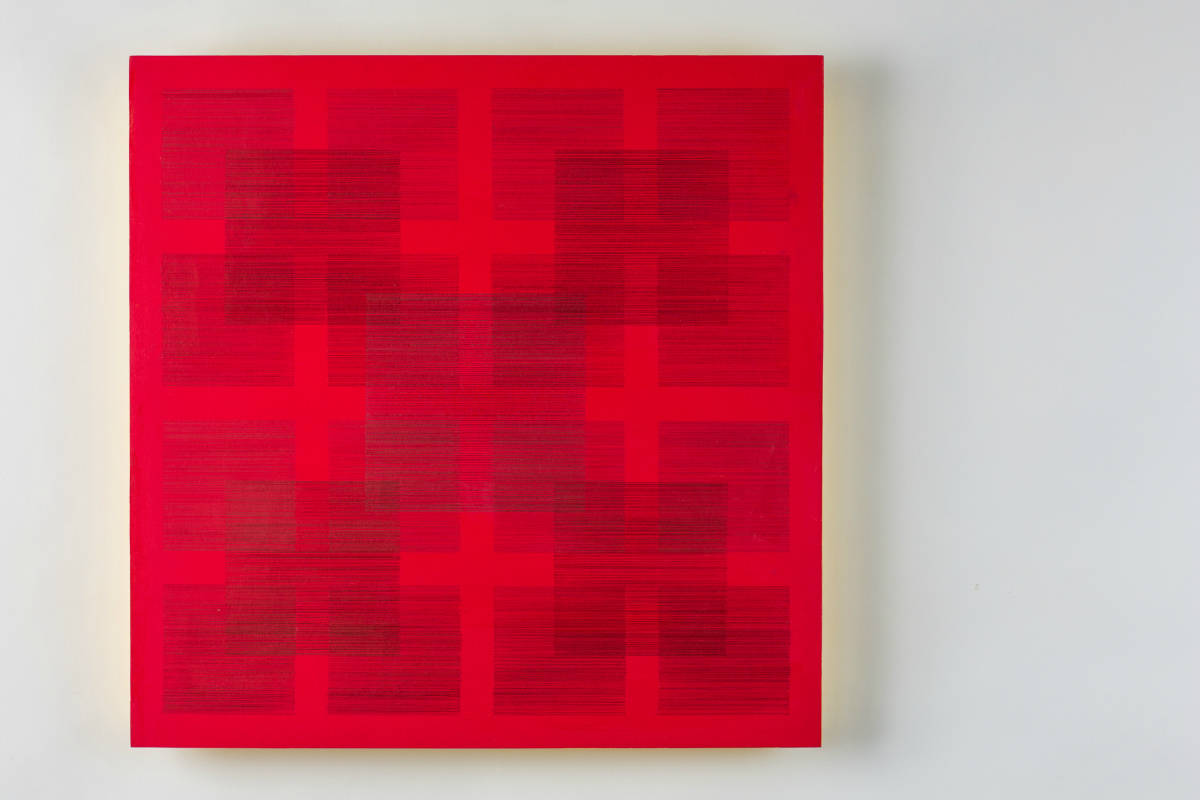

Harmonizations is a divergence from her signature line-and-band work. A series of squares with intricate lines, each one is slightly different, yet all meld to create a shimmering design. Each painting looks one way as you look at it straight on; if you look from the side, its depth and intricacies change entirely.

Orchid, photo courtesy of Susan Schwalb

“The creative process is peculiar,” Schwalb says. “Most work doesn’t have the clear narrative everyone would like. There is a narrative; it’s just not as obvious.”

Today, Schwalb draws primarily with styluses. In her earlier years, she often used wider, heavier bars of silver to make her marks, which was hard on her hands. For the same reason, she only shakes hands with her left. “I have to save my right hand for my work,” she explains.

Part of that work involves spreading the news about metalpoint as an art form. While Schwalb would prefer to answer questions about the intent of her art at her shows, she often carries a piece of paper and a silverpoint tool in her pocket. “In the end, I surrender,” she says. “They want to know. It looks like a pencil, but it isn’t. It’s shiny, more fine. People are curious. What is this?” And so, she tells them.

For more images of Schwalb’s work, plus a look around her studio, visit our subscriber-only gallery.