In December, we profiled Angus McCullough as an artist to watch in 2016. He’s made the most of this year – so far.

What has multidisciplinary artist Angus McCullough been up to since initially impressing Take Magazine staff and MASS MoCA curator Denise Markonish in 2015? The answer – an impressive amount. The artist published a pithy book of photos, curated a show lending a complex historical context to a 700-acre farm once owned by his family, and rode a train over 2,700 miles to the desert where he staged an intellectual stand-off with the social construction of time and industrialization. Clearly, Angus McCullough is some kind of meta-human and we feel justified in having him on our list of artists to watch in 2016.

Connected Through the Land & Corn Crib

These two intermingling projects exist on a 700-acre farm once owned by McCullough’s family, and strive to educate the community about the history of this now publicly-owned and accessible land. Yet, the two installations address the complex history of the location in different ways, “…it’s been a way to look into agricultural structures and how to reconstruct lifetime farms in a very specific frame. The projects are also an act of looking into land issues. Can humans own land? Or are we stewards of the land? How is it used? How is it perceived? How can we understand ourselves better through understanding the land we worked?”

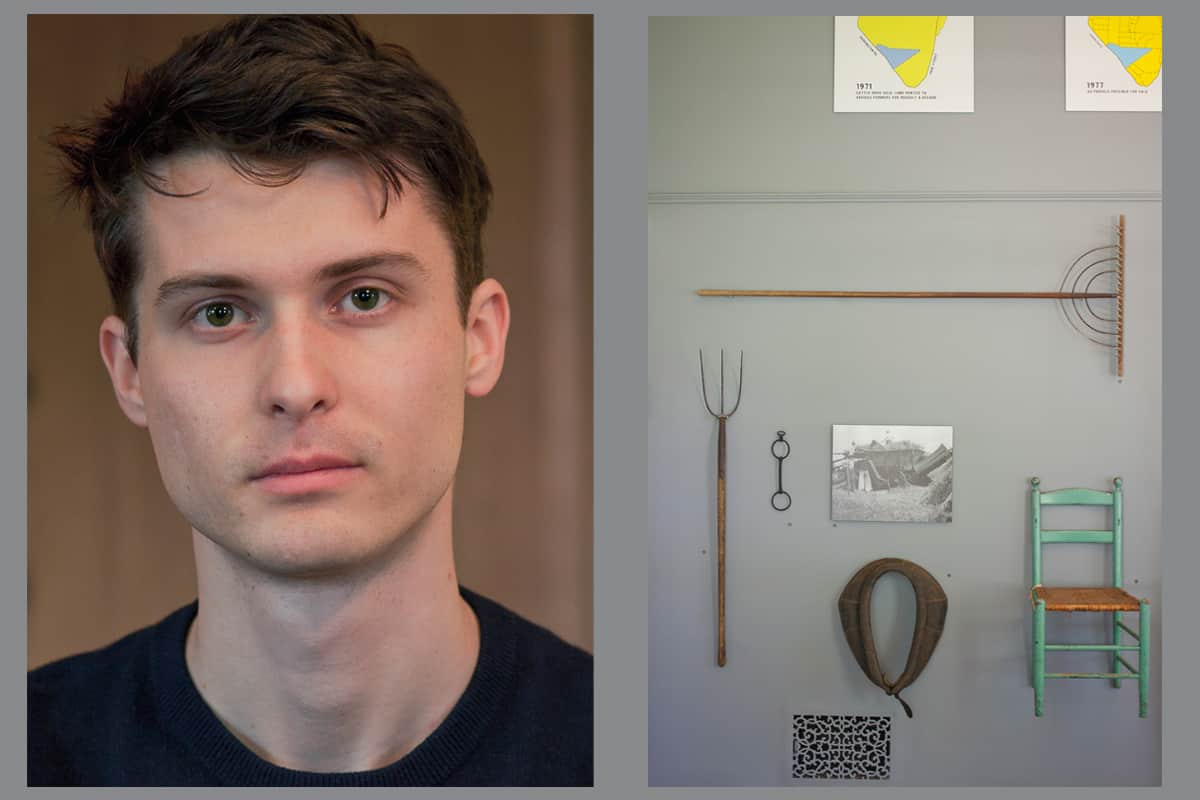

Angus McCullough and an image from ‘Connected to the Land’

His artistic attempt to make sense of this intricate history began many years ago when he decided to reject the normative compulsion to frame the history of the farm in the narrative of uncomplicated, glowing American Exceptionalism. According to the artist, “…this show is displayed in a historic mansion. These shows are usually about wealth, material legacy, and opulence. At this point, the show focuses more on the working-class, day-to-day history primarily because these are the people who were really looking at and working with the land at the time.” McCullough hand-picked old photographs with small employee bios, tools actually used on the land, and other dusty documents to foster a more honest depiction of the day-to-day events on the farm. “It’s like reaching into a deeper historical awareness through these artifacts. All of these things touched the soil and were held by the people. They’re about as close as you can get to a direct source of literally feeling time.” Angus plans to continue the historical and artistic exploration of the farm through Corn Crib, an architectural building on the property from the 1940s. Once the building is restored, it will house a set of artifacts and images that address how the farm and its successes are, at least partly, a complicated byproduct of the active and indirect displacement of the region’s native peoples.

Bushes of Bennington

If you spotted Angus in your hometown, crouched down and intensely examining a lumpy and scraggly arrangement of shrubberies at the corner of the street, this is why. The collection of photographs titled Bushes of Bennington County is exactly what it sounds like – a comprehensive examination of, according to the artist, almost all the bushes in Bennington County, “I did take over 3,000 photos, so I probably got about a third of all the bushes in Bennington. At first, I took photos of bushes I hated or ones that were interesting to me and I sent them to some people as a joke, but then one of my friends said, Well…are you gonna do all of them?”

Bushes of Bennington | Angus McCullough

The project may seem inconsequential, and perhaps a bit too irreverent by mean-spiritedly poking fun at how non-art-makers deal with aesthetics in public places. However, McCullough’s love of his subject and curiosity about how these bushes reflect cultural overtones is genuine, “Ultimately, this project is about engaging with where you’re living. It started as a joke, and the humor never left the project, but I would like to give these bushes dignity. I try to see the context, the shape, and the rules about what they’re allowed to do and what they’re not allowed to do.”

Boxo Residency

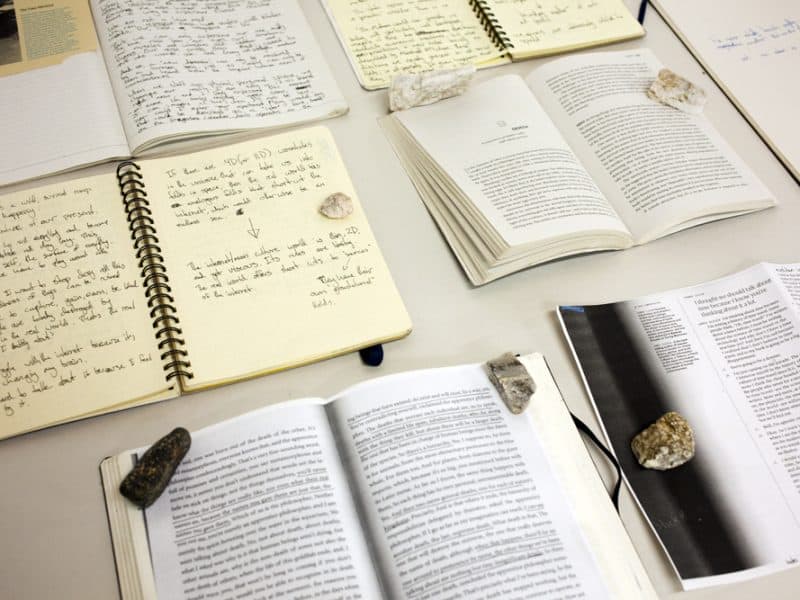

One of the most artistically relevant experiences Angus had since we last caught up was his artist residency in Joshua Tree, California. The artist set out across the country to steep in several subjects that have been common themes amongst his work and his life for a very long time, “…it was a way for me to get into a project that I had been thinking about for a long time and had always been trying to do. I’ve been looking into the standardization of time, times zones, my own intense experiences of déjà vu, really lucid dreams, and this awareness of cyclical time that has always bothered me. For a long time, I was like ‘Time doesn’t exist! This is bullshit! This is just some awful conceptual trick that we’ve all fallen into!‘”

“The work out in the desert started with going there. I took the train to California on Dec 29, 2015, so I could celebrate New Year’s Eve on the train while we’re [sic] moving. We celebrated New Year’s four times, once with this person from Paris, at 2 PM we counted down and popped a bottle of champagne. It was this absurd trip through the new year to get to the residency.”

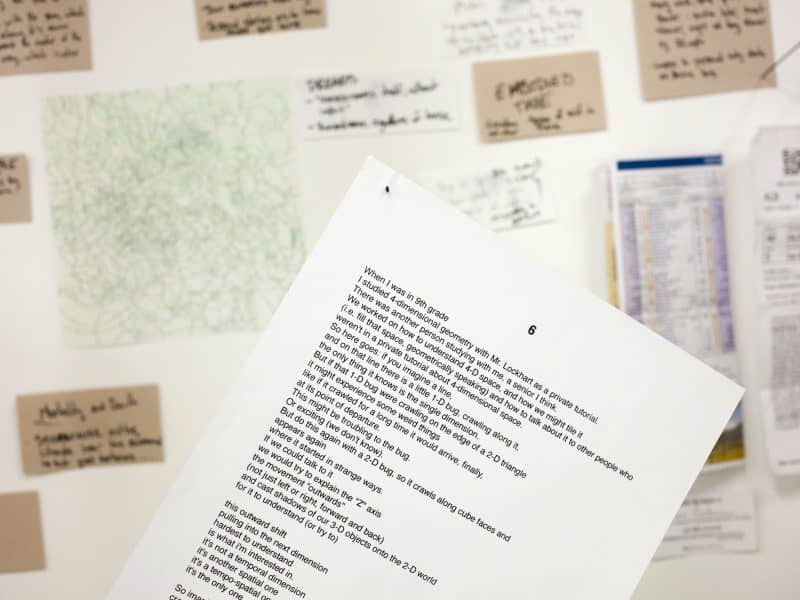

The products of the residency were many and varied. Angus’s capstone installation featured a massive wall of notes, live music, video, recorded sound and several other mediums. Angus felt that installation would be the only suitable way to relay to audiences the complex and, admittedly, slightly convoluted nature of the artistic and scientific questions he was addressed, “[the installation] presents a very particular possibility in that it asks us to be alive in real space with media, with work that someone else has done. When you can harness that power, and I’m not saying I can yet but I feel like I’m beginning to understand how, it allows you to speak in seven ways at once.”

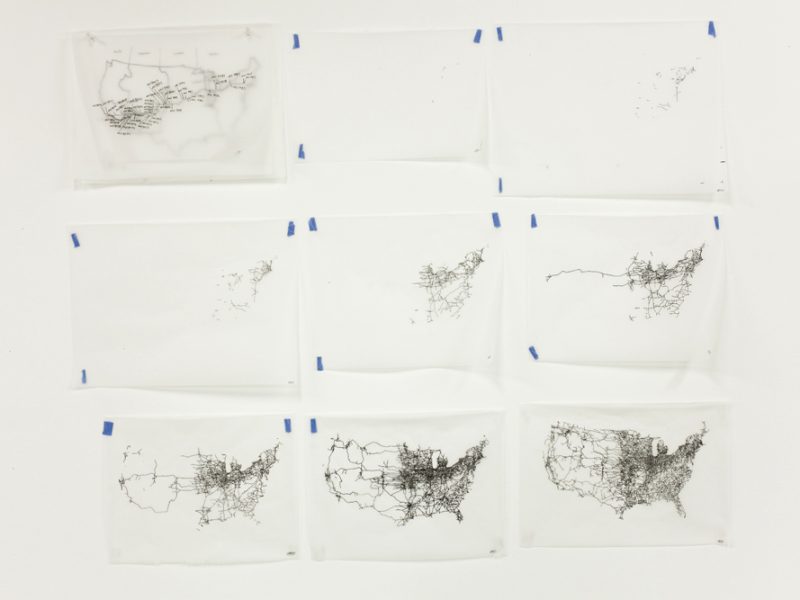

What’s most fascinating about McCullough and the work he’s done since late 2015 is the diversity. Whether Angus is intensely photographing a row of boxwood, sifting through old photographs of early 20th-century farm employees, or hand-rendering a map of all the railroad track laid in 1918, he’s working to lend dignity to the seemingly banal. The artist taps you on the shoulder and demands you reckon with the bushes awkwardly arranged in your hometown’s public park, while simultaneously asking how the act of observing that object affects space-time. McCullough’s work draws attention to the overlaps in our separate day-to-day circumstances and asks us not to acquiesce, but to thoughtfully digest our version of reality.

Angus McCullough is an artist living in Bennington, Vermont. You can see Connected to the Land at the Park-McCullough Historic House until October 10, 2016. Be sure to follow the Corn Crib blog, and follow Angus on Tumblr and Twitter.