It’s no secret that the Take Magazine staff loves the folks at BreakfastxLunchxDinner and all the work they do for Hartford. Below is a post that appeared on their website back in January 2016. We’re pretty jealous that they got to chat with Arien Wilkerson before we did, so we’ve decided to share their interview on our new website. Be sure to follow BreakfastxLunchxDinner for all their posts and events, and be on the look-out for their upcoming Friendship City Dance Carnival Part II, September 10 at Eight Sixty Custom.

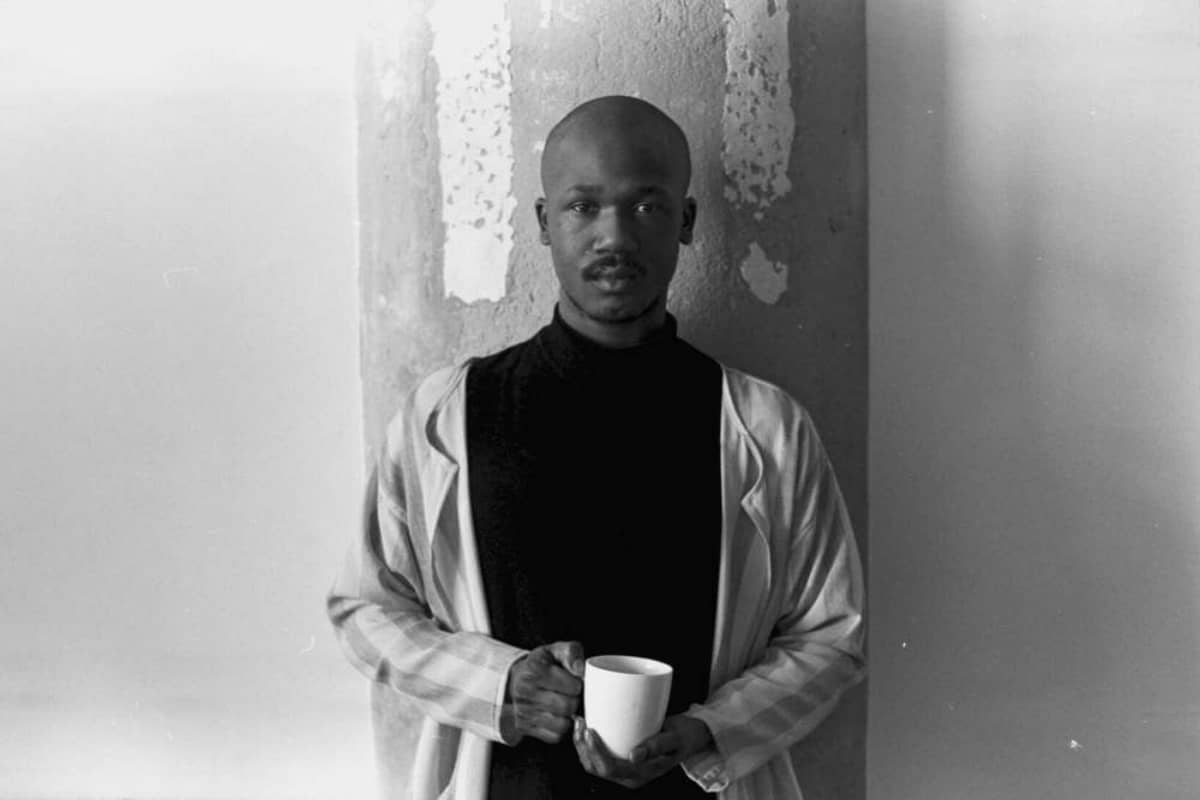

He’s too black, too vocal and too flagrant. He’s also one of the few indispensable figures in Hartford’s ever-continuous push to art and cultural prominence. Say hello to the city’s new brash monarch.

INTERVIEW BY: ONYEKA OBIOCHA & AUNDREA MURRAY

PHOTOGRAPHY: JOSHUA JENKINS

Onyeka Obiocha: Thank you for coming out today, man.

Arien Wilkerson: Thank you for inviting me. I like interviews. I never get a chance to talk as much, so it’s cool.

OO: I mean, we have conversations like this all of the time.

AW: Right.

OO: Which is interesting to me because I can tell you – I have learned a lot about community art in terms of what art can do for the community through a lot of things and a lot of initiatives that you’ve propelled or that you’ve been apart of. Whether it’s Tnmot-Aztro, whether it’s Hartford Denim Company [or] even helping out with The Brother’s Crisp in some ways, even helping out with Breakfast Lunch & Dinner and de Muerte, you know what I mean?

AW: I threw the Saint Colt birthday bash. That was fun.

OO: Why Hartford? And what drives you to push the art community as you’ve done so far?

AW: Well, the only reason why it’s Hartford is because I’m born here. It’s as simple as “rep where you from”. I also believe that if you can’t make it where you’re from, then you can’t make it anywhere. I feel like it’s the opposite of people who are like, “Oh! I left Michigan or I left Indianapolis because there’s nothing there for me.” And that’s fine because sometimes there isn’t. But if you can’t make it there, then why are you leaving to try to make it somewhere else?

OO: Fair point.

AW: I felt like that was huge to me. Do I want to go out there and shuck and jive and sell myself for a place that could eat me alive if I don’t know it? So I think that’s kind of what it was: being comfortable and being uncomfortable at the same time. Being comfortable to be here and then being uncomfortable to know that, ‘OK I want to go, but I can always come back.’

OO: So for the Hartford arts community, how do feel you’ve been doing? What are some areas you wish you could improve on personally? And then as Hartford artists, how can we all get together and improve on that to push it so that we can all make it where we are?

AW: To be honest, I’ve never looked at what I’ve done. [laughs] Just because I haven’t looked at it. I think it’s a little bit of both. Predominantly, one big help was Hartford Denim Co. That was a huge help from coming back from Tel Aviv. Being able to have a platform to be young as fuck, and to be working right next to Kristina Newman Scott and Andres [Chaparro] and Lauren [Varjabedian] – whose last name is impossible to say. It was interesting because I was very young. No one knew the concept of just see things for what they are and do what you can. Not try to get everything done because you feel like it has to be done. Do what you can do without asking for help and then the rest will come.

OO: Got it.

AW: So I think it was a lot of that. That Hartford Denim “Do It Yourself” mentality – kind of like surviving in the wilderness that I approached in a sense of surviving in this urban wilderness. People and politics are just as crazy as fucking animals in the fucking wild. [laughs] They’re the same thing. So approaching it like that, just being very animalistic and aggressive. I think from now to then I’ve been less aggressive than I was before because now I feel like the much more important I’ve [gotten], the less aggressive I have to be with people who won’t listen to me. But when I first started, I was just aggressive as fuck you know? I think that was something that’s interesting. And I still [am aggressive] in a sense of being able to approach anything with an open approach.

OO: I personally like the aggression because I think it’s on both sides of the coin.

AW: Right.

AUNDREA MURRAY: Describe more of that aggression. What’s that like?

AW: I think that aggression is just being able to approach someone right in their face, look them in their eye and say, “Hey, what do you do? How does it help me? How does it help this city?” and them being like, “What? Haha. Hi, I don’t know what I do.” or “I don’t know how I approach the city.” Or some people being like, “Hi, I’m so and so. This is what I do. This is how I approach the city.” You know what I mean? It’s being flat as fuck. There is no bush. There’s just you and I and this Goddamned desert.

OO: You’ve been a real art advocate especially for the North End.

AW: Yeah. That’s kind of how I started, too. I think it was predominantly from being in Tel Aviv and that was the last place that shook me up with realizing the difference between a refugee and a citizen and really understanding what that was like.

OO: What do you mean by that?

AW: Just seeing how you can be in the same place and still be very separate from someone. OK, so we’ve kind of “deleted” racism, so what? We’ve kind of “deleted” the idea of bigotry.

OO: In Tel Aviv?

AW: Just everywhere. We’ve so-called “deleted” it. Racism so-called doesn’t exist anymore, bigotry so-called doesn’t exist anymore, but it does. Racism still exists, bigotry still exists – you know what I mean? Seeing that idea and seeing a real refugee next to a Jew and though he’s Black and that person’s Jewish, or that person’s tan and Palestinian, they’re all citizens but people still [place them separately].

The Matrix of Denomination. That’s what someone said to me. “Things that separate you,” and that got me thinking about when you take your SATs [and it asks], “Are you male? Female? Black? White? Asian?” Shit like that. When you apply for your food stamps – just everything. Census Bureau, you know? “How many people live in your home?” Those things didn’t make sense when I was younger. Or it just didn’t make sense because I wasn’t looking at it like that until then.

OO: I feel like you translate some of that into your work, too.

AW: Yeah. I guess. I feel like there’s always a sense of identity in my work. Everything trickles. There is a path that you walk down. It’s never a journey. It’s an ‘immersive experience’, which I think is cool. You’re immersing yourself into something and then getting out of it.

AM: How old are you?

AW: I’m 24!

AM: So you’re 24, you sound like this razor-edge of a person. How did growing up hone that? How did you sharpen yourself to get to this point?

AW: Just from not having anything. Just from the ability to live with not having anything. Then you start to know what you want, you know? And start to know what you need and not only what you want. Like, “What do I need?”

AM: What do you need?

AW: What do I need? That’s interesting because it’s a difference. It’s like, do I need stability or do I not need stability? Do I need money or do I not need money? Now as I get older, it’s hard for me not only to define what I need but to say what I need because everyone needs the same shit! I’m kind of like, “I need that. But that person needs ‘that’ too.” I’m starting to realize that everyone’s really the same in that kind of context of everyone needs money, everyone needs stability, everyone needs consistency, [and] being able to go back to the same thing or to do something new and still have the same basis.

I was talking to my friend George who is a volunteer at the Boar’s Head Festival and he is apart of the Hartford Symphonies Orchestra. He was like, “No matter what, we always have 400 people in our shows a night. We know the starting base of any amount of money that comes to see Hartford Symphony Orchestra is 400 people. It can go more than that, it can go less than that. But we know we always do a range of 400 people in the audience,” or some shit like that.

The point he was trying to make is the idea that they have something consistent. So no matter what, they know that they have 400 people that are always going to see a show or 300 people that are always going to see a show at Hartford Symphony Orchestra. It’s that kind of idea of being able to maintain that and that’s what I feel like every artist needs: that consistent thing that you can go to. When Rihanna drops an album, she has an album, a video, a tour, then vacation, then she does it again. Every artist needs that.

OO: Can you talk in general about Black Boy Jungle and The Projector Series and if someone were to come see the show at Real Art Ways, what they should expect from The Projector Series?

AW: Well, Black Boy Jungle is completely different from The Projector Series because Black Boy Jungle was interesting in a sense that I just feel like The Projector Series and Black Boy Jungle are climate pieces because I choreographed them at weird times. Every time I think about The Projector Series, it’s always done in the winter and we’ve always done it in November, December, January. We’ve always done this piece when it’s cold. [laughs] I’ve always found that to be very weird.

And with Black Boy Jungle, we made it in the summer. I feel like Black Boy Jungle is the story of American identity told through reggae music, which was fun because I’ve always wanted to use reggae music. I’ve always wanted to use Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry and King Tubby and I’ve always wanted to indulge in that type of, still, very political way of thinking. Reggae music wasso political back then. In the 60’s and 70’s, it was more political than what it is now. And they said more than what you can probably say now.

There were songs like “Straight to the Capitalist’s Head”, as titles. Just sharp edge, you know? They’re not missing anything and that to me was important as fuck. Let’s just take the essence of being able to be next to your fucking father on the island in the God damned truck, driving down the road with your hair in the wind meets who am I? How am I going to define myself?Where is it that I come from? What is the idea of an American, the perfect American? How do we make up an American? How am I an American but still have ancestors that link me to a place that is not here? Am I essentially American or am I not? How does that define everyone? Especially in my company. [Black Boy Jungle] was about them. It truly was about the members of the company that I have. I have six beautiful dancers and they’re all different. Literally. One’s Greek, one’s Buddhist – he is Malaysian – one’s Mexican, one’s German and Polish and half-Black, one is West Indian.

OO: What’s The Projector Series?

AW: Now The Projector Series was cool because like I said to you before, it’s a work of iteration. It was a one man solo done in a room [at about] 17 minutes long. A 17-minute solo that was non-stop moving. I kept changing, and everything was happening in front of the audience. When I changed clothes, when I did everything, it happened in front of the audience – it was a one-man show. I liked it because I’ve never done a one-man show before.

Coming from dancing in companies to doing a one-man show was fucking scary, but it was exhilarating as fuck because you start to defy what you want versus what you need. As artists, what do I want to say and what do I need to say? So that was kind of fun too.

AM: You said that it was broken into pieces? The Projector Series?

AW: It was kind of done like that. It was a 17-minute long solo then it became a one-man show that had duets that spurt over time. I had two dancers just to perform in two different sections of the work. Then I kind of stopped and I don’t know. I think that’s weird now that I think about it.

AM: Now that you’re thinking about it, what made you do it that way though?

AW: I think it was more so because of the timeline of it. I was actually apart of the first hip-hop dance company in Connecticut and that was ‘the thing’. I was the Rehearsal Director of the company. We performed everywhere. The Riverfront – everywhere. It was like ‘the thing’ and it was cool because I still have the picture in the brochure and the 2014 featured events of my face and me dancing. It was really cool, it was a really great year.

Before that, it was just weird for me because I left this company and I wasn’t necessarily dancing and Tnmot-Aztro wasn’t necessarily about “dance”. I felt like I could get dance from somewhere else [while] Tnmot-Aztro was about being able to say things that I couldn’t say through not dancing. It was fashion, photography and film. A lot of films we just did a lot of impromptu films on cellphones and fucking bullshit-ass cameras and it was just about being on the block and really not having [anything] and not having [anything] to do and really being bored. When you’re really bored and really have nothing to do, you really start to figure out what it is that you want to do and what it is that you need to do.

OO: How did you get the name Tnmot-Aztro?

AW: That’s so funny because I found the ‘Tnmot’ and my boy found the ‘Aztro’. The Aztro came from Quasimoto. That’s really cool just because we fucking love Quasimoto and we love Madlib. That’s just a mutual thing. I’m a hip hop kid, so before ballet and before modern dance and African and West African styles, there was hip-hop. I would never have known dance if it wasn’t for that so that has always been first and foremost to me within the company. It has to stay connected to ‘the root’ of the street.

‘Aztro’ came from Astral Black and Astral traveling and the whole Quasimoto vibe of getting high and motherfucking making art, you know? We love to smoke weed and we fucking love to make art. The ‘Tnmot’ – I didn’t want something that was Spanish, I didn’t want something that was Greek, I didn’t want something that was French. I wanted to find something that was really interesting to me. So I looked up Macedonian language and it’s a really hard ass language. There was talk about it being Russian or it being Turkish. It’s the south Slovak language. It’s Middle Eastern enough. It’s hidden [and] people have to look it up which is kind of fun. I wanted something that was just hard. ‘Tnmot’ means “team”, so it’s just ‘Team Aztro’. And ‘Tnmot’ can mean “team” or it can mean a “hard substance”. So the idea is that rocks are built together in one big clump.

OO: You’re a very energetic guy. You have a lot of energy and you talk fast. I have never understood you as a human being until I saw you teach dance, and when you were in your element, I understood for the first time who Arien was. How did you get introduced to dance and in what ways do you feel like that represents who you are?

AW: Well, dance and language is like any other language. I’m not fluent in a lot of other languages as I should have been, so I feel like dance makes me bilingual. Before you watch out for sounds you watch out for movements. It’s a language. I didn’t see it until I was a lot older, but I started dancing because I was just bad as fuck growing up. Nothing else [would stick], you know? I loved Gene Kelly. I knew, also, that I liked men from the time I was five, so I knew I was a homosexual. I knew all of these things about myself, so I was just like I need to figure out how to defend myself. It was more about me figuring out masculinity as opposed to the language of moving. So when I discovered hip-hop, I was always dancing. [When I was younger], they would always be like, “Arien, dance. Dance. Dance. Dance. Dance.” And it was sloppy and it was horrible, but it was filled with a lot of energy and a lot of passion and a lot of just raw ability. But it didn’t become a conversation until I started b-boying.

OO: So you learned masculinity through dance?

AW: I learned masculinity through dance and through watching male dancers growing up. I actually watched more male dancers growing up than I watched female dancers. My parents were like, ‘OK. He likes to dance, so let’s try to put on males who dance’. What Black home did not like Michael Jackson at that time? So you were always able to watch shit like that and that was easy. I guess getting older and my mom realizing that I was different, [and me] realizing that I was different than everyone else, she brought me to Artist Collective. It just kind of happened like that.

I met a woman by the name of Jolette Creary. She’s the owner of Studio 860 and she asked me, ‘What are you doing on Saturday? Come back.’ And that was that. It was like boom! Started dancing. And I stopped for like a year to go play baseball because I guess I still wasn’t even convinced that I going to dance. I was going to play sports or do something masculine. Baseball sucked and my mom was like, ‘Fuck it. You wanna go back to dancing? Because apparently, that’s what you’re good at.’ My parents – thank God – are smart with not forcing you to do what you’re not good at. It was more of ‘Stick to what you’re good at’, which helped.

OO: What’s next?

AW: I mean, that’s the thing: I don’t even know. With this piece, it’s funny as fuck. It’s my decadence. Everybody has that one work, or has those three works. Sylvester Stallone has ‘Rocky’. Everyone has the best thing that they made. It’s that idea that I’m talking about. It’s kind of scary to have something that you know is good and will always live forever, even after you die.

AM: What’s your ultimate trademark project look like to you?

AW: This.. Is.. Not it. But at the same time, I don’t think that I know what my trademark project is because I haven’t had the ability yet to hit it on the nail. The only reason why this is possible is because we know how to do it again. It’s the resource of how to do it again. I don’t know how to do Punching Bag again. It was created in a space that was sourced from an individual that I might not be able to use those resources again.

OO: Just to be clear: Punching Bag was the work you showed at Open to Anything.

AW: Yeah. We can maybe do Black Boy Jungle again, but how do I get 30 vintage trunks from all over the world? That’s what the theme was. Black Boy Jungle was a reggae piece set in Ellis Island and Ellis Island happened way before the psychedelic reggae movement happened. How do you even do that? [laughs]

Once I understand how to source the things and do the things again, then you can start to obtain my work. You really can’t obtain my work because it’s not a painting, it’s an installation. That’s why I say that it’s an installation because it’s not like The Nutcracker. You can do The Nutcracker during any season just because you wanted to. Everyone knows it. It’s something you can source out of anywhere because it’s an easy story to source. It’s my resources. Getting the city on my side would be fun but that’s interesting within itself because I don’t think [Hartford] is ready to support someone who thinks more than they probably think. Everything has to exist in order for things to be done. The city needs to already see that I can fill a place with 200 fucking people every fucking time before anyone reaches out. They don’t give a fuck about what’s new. They don’t give a fuck about the idea of ‘small’.

AM: So how did you do it without ‘their’ help, so to speak?

AW: Well money, yeah. But once you get the money, it’s just the right planning. Simple as that! It isn’t someone else saying ‘Do or die’, it’s you saying, ‘Do or die’. If you’re not moving forward then you’re just not moving. I feel like that’s a huge factor to how we did it.

OO: I feel like now [Hartford] is in a great position to really help some budding artists.

AW: They are! They absolutely fucking are.

AM: Agreed.