Roberto Lugo’s pottery will blow your damn mind, mixing classic Royal Worcester forms, graffiti and some Ghostface Killah.

Here’s what I love in art: made things, and mash-ups of high and low culture, and things that make me think. Sacred/profane, everyday/elevated. I’m a poetry professor, best job in the world. When I’m teaching poetic meter I like to point out that “kaPOW” is an iamb, as in iambic pentameter. And “MOtherFUCKer” is two trochees, like in trochaic trimeter. Big words students don’t know yet and little words they didn’t know they were allowed to use in art. My job is awesome because I get to be the one to give them permission. KaPOW!

So I was 80 percent in love with Roberto Lugo just from looking at his website. There are images of Lugo himself, beautiful self-portraits, his body big and legible in its baseball caps and musing open mouths. There are pandas that loom like his spirit animal, pandas that look like him. One patchwork panda is aiming two guns, an Eats Shoots and Leaves joke. His paintings are beautiful, detailed, accomplished, and look like graffiti—the drip marks, the defiant fonts. My favorite says “TO THAT ONE GUY WHO SAID I SUCK YOU LOSE.” (Five iambs, by the way; iambic pentameter. This line is part of a sonnet I want to read. Can I write it? Can I write it and give it to Roberto Lugo as an artist-crush mash note?) When he talks about the difference between teaching little kids at summer camp and teaching college students, he says, “Kids at camp feel limitless and have to be taught very little, as their imaginations are boundless. College students often have to be taught to be as fearless as their childhood selves.” He’s giving them permission!

Photo by Kenek Photography, courtesy of the Wexler Gallery

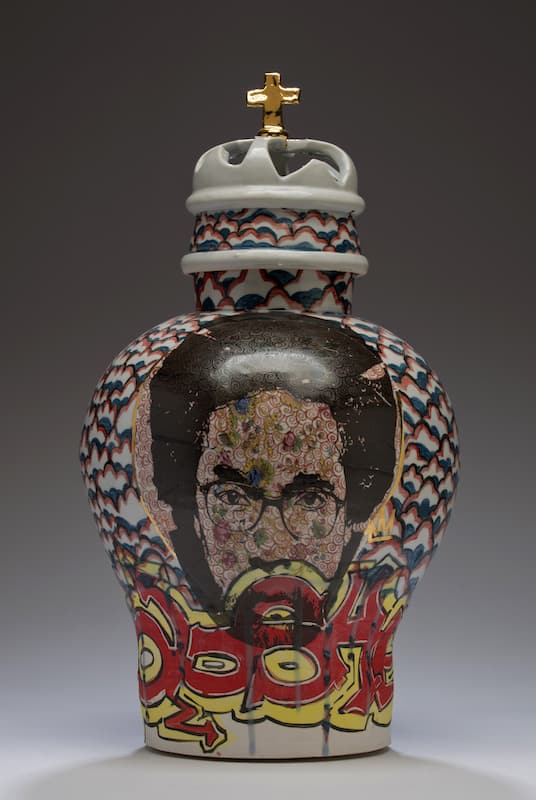

Roberto Lugo’s email address is thismachinekillshate@gmail.com. There’s a kind of earnest tenderness there, and it translates to his work—affectionate portraits of real faces with sideways glances, on jars and teapots loaded up with color, pattern, ornament, crowns, touches of gold. They glorify, deify everything they feature: Bernie Sanders, Trayvon Martin, chubby sparrows breathing puffs of visible vapor, Abe Lincoln, Ghostface Killah, Frida Kahlo, Bert of Bert and Ernie, Biggie Smalls.

Lugo refers to himself as “a ghetto potter,” adding, “The word ‘ghetto’ can be seen as a negative, but I equate ‘ghetto’ with the word ‘resourceful.'” His dad used to take old washing machine engines, MacGyver them into massive food processors with tin can lids, make a shit-ton of masa, and sell it for cash money. One recent show included a video, “Ghetto is Re-Source-Ful,” that shows Roberto Lugo walking around garbage-strewn streets in Philadelphia, finding a shovel in a trash heap. We see him use it to dig up some soil to sieve to make clay, see him tagging a wall with a chunk of broken brick as a marker, drawing one of his signature crowns. The video shows him making a potter’s wheel out of a trashed tire hub, a Goya can, a tree trunk someone has tagged “SPIC,” and a lot of duct tape and rope. Then he uses it, makes a new pot on the spot.

His 2015 show at Ferrin Gallery, “Ghetto Garniture: Wu Tang Worcester,” isn’t talking about Worcester, Massachusetts, but Royal Worcester, maybe the oldest English porcelain brand that’s still making stuff. By creating a Royal Worcester style of decorative vessel with street graffiti looks, pairing traditional Turkish patterns with the colors and symbols of Puerto Rico, he highlights “beauty in integration and tolerance.” He also makes some crazy pots. Like “Food Stamp Ware:” a blue and white vase with images from a food stamp. Lincoln’s on the five dollar food stamp, so there he is: the reverse side is a landscape from the same bill.

“When I grow up, I want to be a ceramics professor” doesn’t occur to most of us—not Lugo, either. When he was a kid in Philadelphia, playing in the abandoned cars and tagging the neighborhood with his brother, he got work at a Christmas wreath factory. He worked there every year from the time he was 13 until he was 19. He also worked as a doorman, a security guard, a death claims specialist, a call center receptionist, a shop clerk, and a bus boy. The first thing he ever made in clay was a fire hydrant soap dispenser, “to commemorate my father and I showering in the fire hydrant.”

Photo by Kenek Photography, courtesy of the Wexler Gallery – “Ol’ Dirty Bastard (ODB) and Dr. Cornel West,” 2015

Now he’s got a sweet job teaching ceramics at Marlboro College in Vermont, a wife and baby, and a solo show up at Wexler Gallery in Philadelphia through June 11. The video diary entries he posts on Facebook are short raps about whatever’s going on. The one about getting to go back to Philadelphia, his hometown, includes: “They used to hate me, but now they pay me … I tell them what I do and people be like, ‘Really, dog?'”

This kind of generosity and transparency comes through in Lugo’s teaching, too. He still remembers the first person who told him he was a good artist: Professor Jay Spalding at Seminole State College. Lugo is finding fresh ways to honor that memory. One of his videos is a sort -of how-to for his students, after Biggie Smalls’ “Ten Crack Commandments”—“Ten Pot Commandments.” Number Nine: “No, that glaze is not fine. You need to sieve that shit twice so it come out nice.” He shakes a finger at the screen. Who doesn’t want to take a ceramics course with this guy? “Follow these rules you’ll have mad fun making stuff, less time breaking stuff.”

His life, his voice, his body, is at the center of these beautiful, surprising pieces. I kept thinking about his body, why it is important to me—how he dresses, his face, big human-loving eyes. So often they’re featured on the pots themselves—these fancy urns with a portrait not of a duke or the queen of England, but some guy who looks like he lives in my neighborhood, and we smile when we run into each other at the bodega.

That fixation I had with seeing this real guy on these fine things made me ask myself why I was so surprised and delighted by it, what that meant. What ideas was I carrying around about what ceramic artists look like, or whose faces deserve to be on a pretty teapot? Do I just figure they’re all white? All dead?

Photo by Kenek Photography, courtesy of the Wexler Gallery – “All about the Benjamins Century Vase,” 2016

I realized I had some ideas about the hands that make simpler pottery, the coffee cups I use every day—my dad is a potter, after all. But this kind of high-end, decorative, gilded porcelain, things that belong in vitrines in museums, they seem to me unworldly, sui generis, untouched by human hands. Not something I deserve access to, something anyone is allowed to touch. They come out of a fancy factory in The Europe, and rich people get them for getting married.

But there he is, a guy from Philly with a backward baseball cap and a Puerto Rican-flag bandanna, humanizing these beautiful objects. They are delicate and real, claiming status and fame for their maker, giving us access to their kind of perfection. Roberto Lugo makes dirt into delicate machines that are very busy exalting us all.