Jedediah Berry reinvents storytelling with the dark tale of The Family Arcana

It was the middle of the night when writer Jedediah Berry first heard the voices. “A chorus really,” he says, speaking in the rambling house he shares with his partner, Emily Houk, and a host of other Amherst, Massachusetts, artists and musicians. “It feels lucky when something comes out of nowhere like that.”

So lucky, in fact, that Berry forced himself to get out of bed and start writing. He didn’t reach for his computer, or even a notebook, but instead grabbed a stack of index cards. “I think I wrote five or six of them that night,” he recalls. Each card contained its own small story, told by a different voice.

Berry is well tuned to the reception of midnight voices. The protagonist of his first novel, The Manual of Detection (The Penguin Press, 2009), is a detective to whom clues appear in dreams. The book, which won the 2009 Hammett Prize for crime fiction, was hailed by the New Yorker as “the kind of mannered fantasy that might result if Wes Anderson were to adapt Kafka.” Berry had once envisioned The Manual of Detection as a type of Choose Your Own Adventure story, although he ultimately wrote it with only one ending. But after the novel’s completion, Berry’s interest in multiple versions of a story remained, which might explain his attention to those voices and their sometimes-contradictory tales.

The Family Arcana is → composed of 52 stark prose-poem narratives that tell a shifting story.

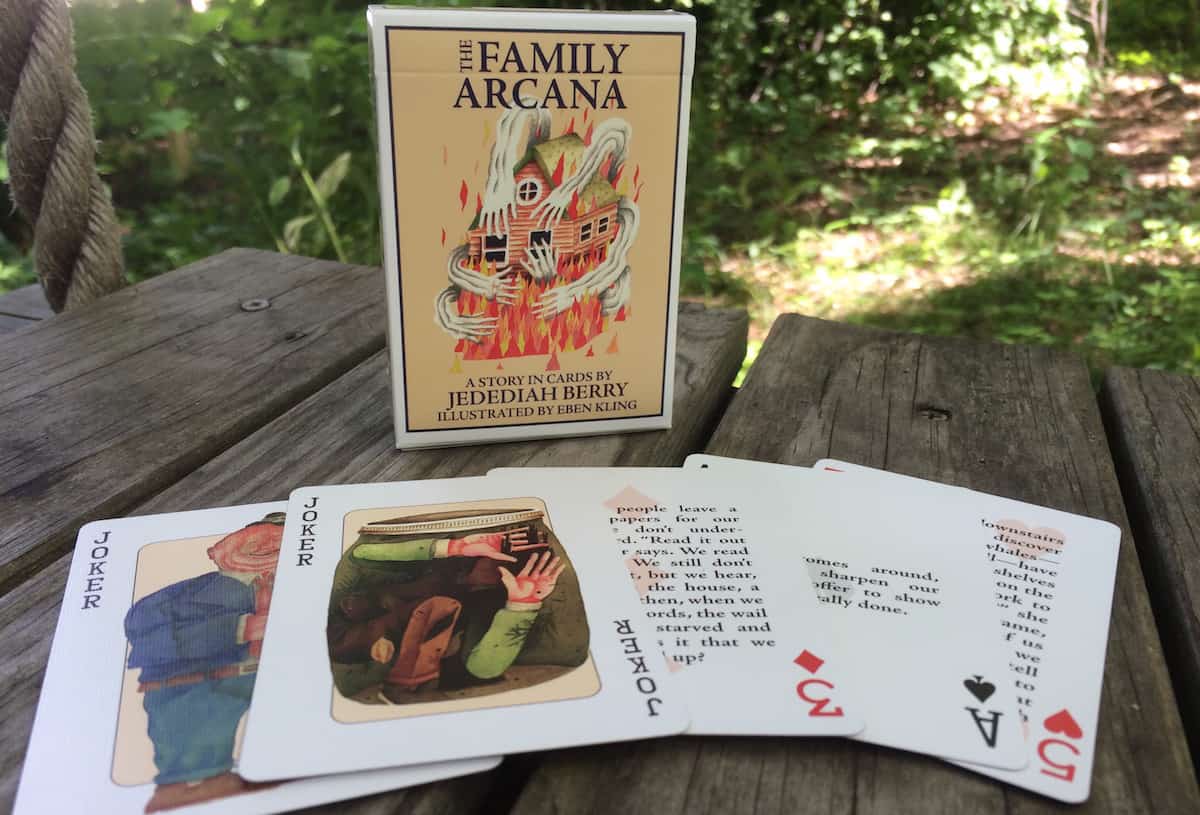

Those voices, Berry quickly surmised, were a pack of siblings with some dark tales to tell. Think disappearing and reappearing children; think bankers hidden under floorboards. Berry crafted these dictations into The Family Arcana, a haunting narrative of a family’s fight to keep their decrepit farmhouse from foreclosure and their buried secrets from the light of day. But here’s where it gets (more) interesting: The Family Arcana, in keeping with its index card origins, is not a book. It’s a deck of playing cards that can be shuffled, cut, and read in any order, creating a nearly infinite number of possible outcomes. Printed by the United States Playing Card Company, The Family Arcana is composed of 52 stark prose-poem narratives, any one of which can be the story’s first line or its last. “Taken as a whole, it tells a story,” Berry explains. “It’s just a shifting one.”

This narrative feat is made possible by Berry’s careful attention to voice and pacing in each card. First lines cast either a wide and suggestive net (“How it goes is this.”) or are compellingly specific (“Father buries himself in his sleep again.”). Each last line contains both closure and possibility, like a flower that blooms or wilts depending on the time of day (“And then we will need more words, and heavier boots, and a song like a lantern to make us brave through the night.”). It takes a reading of only a few cards to realize that Berry is a master of the subtle cues and linguistic evocations necessary to make these individual cards come together as a story.

“The appeal is the mutability,” says Kelly Link, author of Get In Trouble and cofounder of Small Beer Press, where Berry is an editor. “It’s quite a feat to pull off a story that thrives on being rearranged.”

When I first met Berry, I recognized him as the adult version of the clever and quiet friends my brother once brought home—the ones who arrived bearing velvet drawstring bags of 20-sided dice and armfuls of Dungeons & Dragons manuals. Perhaps it’s because Berry’s appearance is rather boyish: he is slight and wears dark glasses and, on the day we met, a scally cap. Or maybe I sensed the resemblance because Berry has created every gamer’s dream: a complex and malleable narrative whose outcome you can determine with your own hands.

Berry and Houk’s centuries-old Amherst house hides behind a thick hedgerow, and when I arrived for our interview, I had trouble finding the front door. The yard is expansive for a house so close to the center of town. Grass and gravel paths lead to overgrown and shadowy edges that suggest Berry didn’t look far for the setting of The Family Arcana.

The couple greeted me in the charmingly cluttered kitchen and led me up a narrow staircase to their second-floor office. The low-ceilinged room was filled with antique furniture and two large desks, a string of Tibetan prayer flags hanging over both of them. Through the open window I heard the faint sounds of guitar music. It was Matt Lorenz of the one-man band The Suitcase Junket, who also lives in the house. Lorenz makes his own musical instruments and, Berry told me, ferments homemade wine in the basement.

Berry offered me a glass of water before we got started, and when I reached to put it down, Houk warned me of a hole in the side table. I ran my hand over it, and sure enough, there was a drinking glass–size hole, invisible under the faded tablecloth. I was beginning to get the sense that things in this house are not exactly as they seem, and that this makes Berry and Houk—and their gargoyle-like chihuahua, Milton—quite content.

Author Jedediah Berry (left) conceived of The Family Arcana in the centuries-old Amherst, Massachusetts, house he shares with his artist partner, Emily Houk | Photo by Joanna Chapman

“This is an area with a lot of ghosts,” Berry says about the New England inspirations for The Family Arcana. “I try to keep their company.” Keeping company with ghosts is something Berry has done for most of his life. He grew up in the Hudson River Valley, where his grandparents owned a rambling and (Berry says) haunted house on a ridge above the town of Catskill, New York. He is rather matter-of-fact about the haunted bit. “There were definitely rooms you didn’t go into alone,” he remembers.

And while that Catskill farmhouse is the original model for The Family Arcana’s farmhouse, Berry was also influenced by Massachusetts farmhouses where he and Houk have lived, including the one they inhabit now.

“I think something that hangs over the history of this entire place is that there’s no way to completely put out of one’s mind the [deaths from] the conflicts with the natives,” he says. “Part of what I liked about writing this family was that their identity was so slippery. I could let their voices speak for the living and the dead, and not just the ancestors of the settlers, but all the ancestors before.”

This sense of history is part of what makes The Family Arcana more than a deck of dark tales. Many of the cards suggest a history of losses and dangers far deeper than the family’s present concerns. One narrator speaks of a spreading black square on the kitchen floor: “When Grandmother sees it, she says, ‘Oh, that old thing. Your grandfather caught it in the war.’ Caught like an animal? Or caught like an illness? Grandmother just shakes her head. We see the square in our dreams sometimes. If we talk about it, it only gets bigger.”

While The Family Arcana began as a solitary endeavor, after a few months of writing, Berry started bringing mocked-up Family Arcana cards to public readings, where he would have an audience member shuffle and cut the deck. “It was a bit of showmanship,” Houk says. “And people loved it.” Not only were the stories well received, but these public readings also allowed Berry to test his cards and discern what elements of the story were missing from that evening’s shuffle.

At one of these readings—held in Berry and Houk’s current residence—artist Eben Kling asked if Berry was looking for an illustrator. Berry knew Kling’s work and was excited at the offer. Kling did the art for the card backs, the two jokers (a banker and a brother, the latter of whom has been pickled in a jar), and additional illustrations for the deck’s two extra cards. (Berry’s design adheres to the United States Playing Card Company design; in a traditional deck, the two extra cards are advertisements or rules for a card game.)

Other writers approached Berry at the readings, sharing their ideas for similar projects. Houk and Berry began to see The Family Arcana as the first of a series, a larger project involving other authors. “We thought we could publish stories in strange shapes,” Berry says. They decided to start Ninepin Press, and they took their idea to Kickstarter with the hope of raising a few thousand dollars—enough to print The Family Arcana. Their project quickly became a staff pick, and by the time the campaign ended, they had nearly 1,500 donors and a total of $32,000 in pledged support.

Berry attributes this success to the larger culture’s desire for projects like The Family Arcana. “Right now, it’s an interesting moment for objects of this kind, especially with so much happening digitally. This gives us an opportunity to rethink the book as object—what we can do to make this an interesting and compelling creation of its own. And I think people are hungry for that. You see it in music with the resurgence of vinyl. People want an object to hold.”

Artist Eben Kling illustrated the card backs, the two jokers, and the deck’s two extra cards.

Berry is thrilled with the result of the Kickstarter campaign, but he’s clear that that approach was very project-specific. He doesn’t plan to publish more of his own work with Ninepin Press or with an online fundraiser. “What I am excited about is publishing more fiction and poetry by other people interested in experimenting with form and taking exciting risks with language and narrative structure,” he says.

But when I asked him if he plans to return to the world of commercial publishing, Berry was quick to question the term. “I don’t really think of there being two worlds in publishing. It’s more of a multiverse at this point. And while it can be hard to survive as a writer, I am encouraged by the range of possibilities open to those who are willing to play around with different models.”

Berry and Houk are getting multiple opportunities to do just that. They are at work recording The Family Arcana audiobook, with a different reader for each of the deck’s 52 cards. Lorenz is composing and recording a Family Arcana soundtrack. And Berry has designed The Family Arcana Card Game, a classic trick-taking game in the style of spades or hearts, with some twists, of course. (The discard pile is called Poughkeepsie.) In addition, Ninepin Press has published a few smaller card sets to complement The Family Arcana. The first is Cosmogram, a set of 12 horoscopes written by authors such as Mira Bartók and Alexander Chee. The second is a set of recipe and curiosities cards, which were created by Houk along with Michael Gundlach, a Pioneer Valley artist and chef. These cards include recipes for Mother’s Cornbread and Berry Shrub, a traditional colonial vinegar and fruit cocktail.

Berry is excited about these cards. “There are a lot of bad ideas in The Family Arcana,” he says. “I like to think that these recipes are a nod to the good ideas. The recipes say, ‘We have our gardens, we have our ways of preserving food, of living in a way that honors these patches of earth we live on.’”

“The recipes are about pickling food, not people,” adds Houk.

Berry has come to see The Family Arcana as a form of preservation. “I can’t brew beer, and I’m not a musician like Matt who can build his own instruments, but we can create this lasting object. We can preserve these stories. I want to sell The Family Arcana at our local co-op, right there with all the other homegrown offerings.”

While The Family Arcana may have arrived in Berry’s head without warning, it also arrived at just the right time for him. “I moved to Amherst 12 years ago and was happy to find this community of writers and small presses and people engaged in all these interesting projects,” he says. “I knew I would eventually want to do something that came from our place. The Family Arcana is a way to contribute to this community. In the last decade I’ve realized I am, in fact, a local—not a visitor—and I needed to write my way into this place. This story is very much a bridge from one river valley to another.”