John Bell, director of UConn’s Ballard Institute and Museum of Puppetry, is just one reason shows like Avenue Q remain popular.

One of New England’s cultural treasures was hidden in plain sight until 2014. That’s when the Ballard Institute and Museum of Puppetry was effectively pulled from mothballs at the University of Connecticut’s Depot Campus, ten minutes west of Storrs, and given a brand spanking new home at the front door of the main campus.

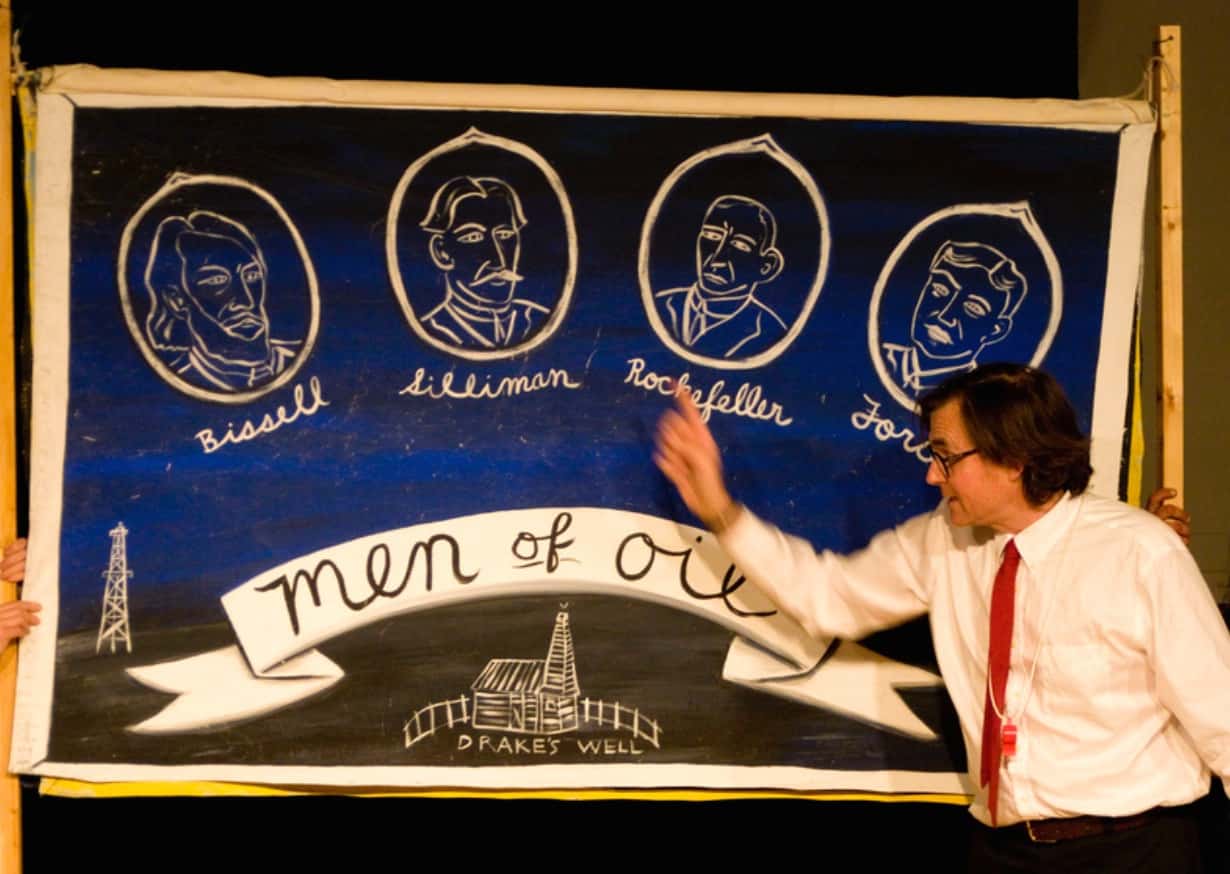

The move was a feather in the cap for John Bell, the director of the institute since 2007 and a longtime puppeteer himself. As a young actor, Bell cut his teeth with the downtown New York performance scene of the 1960s, a political mashup of happenings, experimental film and dance, performance art and puppetry that took place on the city’s streets. While at Vermont’s Middlebury College—from which he graduated in 1973—Bell saw the Bread and Puppet Theater perform at nearby Goddard College, where they were in residence. He was so smitten he later became a member of the legendary group that has become a fixture at mass parades and protest marches.

“I came to puppetry as an actor and was attracted to the variety of things involved,” says Bell. “You could create theater about current events, without having to wait 20 years to get funding or a proper theater venue.”

In that sense, Bell’s path to puppetry differed from that of Frank W. Ballard, for whom the institute is named. Ballard was hired by the university in 1956 as technical director of the on-campus Jorgensen Theater. As a member of the faculty, Ballard added puppetry to the graduate programs in 1962 and taught his first class in 1964. Since then, 400 original, UConn-student-created puppet productions have been presented and Ballard’s collections of puppetry-related material have grown to be one of the world’s finest.

“Thanks to Frank, the UConn Puppet Arts Program has been around for 50 years,” says Bell. “I came at puppetry from a different angle than Frank, who was steeped in the traditional marionette shows and art of puppetry of the midwest, where he grew up. By the time he was in his 20s, he’d created dozens of well-known puppet productions.”

Bell’s mission at the institute, besides preserving and sharing Ballard’s legacy, is to demonstrate how the definition of puppetry is expanding. “We’re interested in pointing out the traditions of hand puppets and marionettes but also looking at puppetry as a modern art form for adults, not just kids,” he says. “We want to let people know that the world of puppetry is vast, part of cultures all over the world. This is important in the 21st century with so much art being technology based, with virtual puppets and the use of digital imagery coming into their own, not to mention robotics.”

Still, whether the artistry is conveyed through hand puppets in a booth or via giant floating contraptions at outdoor pageants, Bell says “the dynamics are consistent.” “Any time humans turn to inanimate objects to tell stories, whether the objects are made of wood, rocks, or shadows—as it was thousands of years ago—an interesting dynamic is created,” he explains. “It is no longer a conversation between humans. We are directing our attention to this object and inspired to make our own connections. By definition, it’s uncanny or mystical. That engagement of the audience is what makes puppetry special.”