Personal histories from the birth of Lupinewood, a majority queer and trans collective in Greenfield, Massachusetts.

The dilapidated Lupinewood mansion is perched atop a winding hill in Greenfield, Massachusetts, overlooking the Connecticut River Valley. Once the lavish estate of the wealthy Peabody family, today Lupinewood exists as a collective of artists, organizers, educators, and health-care providers who are majority trans and queer—all living and working to establish a mutually supportive space for members and transient guests. They collaborate on art and share living spaces, income, food, knowledge, and intertwining intimate relationships, while always prioritizing their core tenets of sanctuary, convergence, and confrontation.

The 6,000-square-foot home and its 4.02 acres of land, which exists on colonized Pocumtuc territory, is a complicated haven for its eight members. Though the collective has existed in some form or another for about seven years, they didn’t truly have a safe and productive home until January 2017, when the group finally moved into Lupinewood.

To learn more about Lupinewood, we asked the collective what existing at Lupinewood means to them, and what they believe is possible at this place.

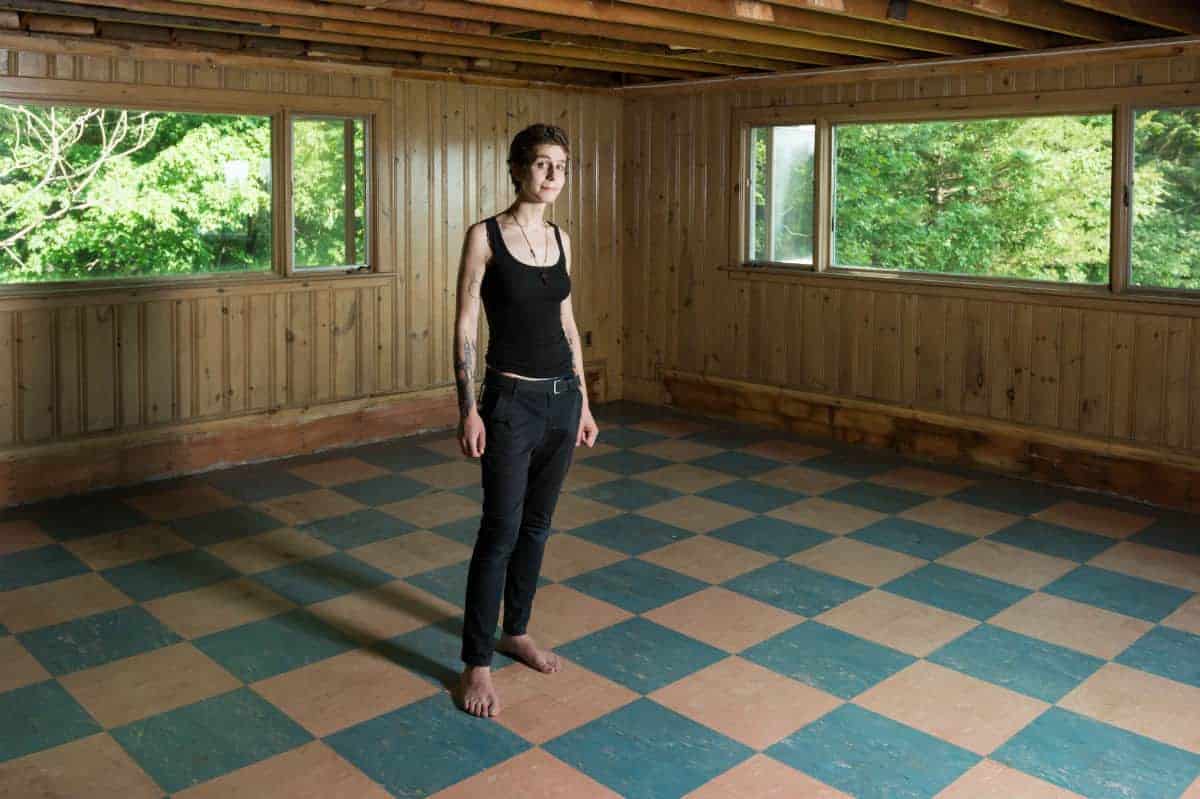

Cea Wiley of Lupinewood. Photo by Caleb Cole

Cea Wiley

Because I’m an herbalist, Lupinewood is a wild paradox for me. It’s a former robber baron’s mansion reclaimed by queer radical artists and organizers; the land, once manicured to perfection, has been reclaimed by plants growing any way they please; the inground swimming pool is getting swallowed by vines. It’s a fairy tale—it’s Robin Hood! Yet, here I am, a white person “owning” and living in structures erected on land stolen by white colonizers through genocide. As I pull weeds out of the gardens here, I think of the ways in which I am an invader myself.

I am starting a low-cost apothecary at Lupinewood, and want to develop a community clinic from it, with the aim of providing alternative health care to low-income folks. I’m setting up a medicinal garden, from which I can source medicine for the clinic, as well as for the street medic and medic trainer work to support front-line struggles. I want Lupinewood’s colonized land to materially combat the corrosion of capitalism on people’s bodies. I want it overrun with at-risk and endangered plants, plants that can be supportive of a complex and generative ecosystem. Additionally, I hope to use this place to host conferences and convergences with other radical health-care workers, using them to deepen the discourse around what it means to live within paradoxes, even as we fight them.

Aurora Rainer of Lupinewood. Photo by Caleb Cole

Aurora Rainer

There’s a long tradition of queers building alternative families and domestic structures. Many folks have had to: their biological families cut them loose, over and over; the domestic models they were handed couldn’t fit them. So many queer people have needed, historically, to be artists. They’ve needed to craft realities for themselves, their friends, and their partners.

I see myself as humbly continuing this tradition through Lupinewood. I am a painter by trade and have a painting studio here, where I make art about queer love and how trans-femininity lives in my white settler body. I take care of the beehives and I apprentice as an

herbalist, tending the food, medicine, and pollinator gardens here. I also help oversee our collective kitchen, keeping track of bulk orders and supply needs, trying to ensure there’s enough soup and tea for whoever’s catching a cold or working overtime. All of these projects are about queer, radical homemaking to me. They’re about crafting a reality in which my partners and friends can thrive, despite the obstacles the dominant culture gives them.

As a femme who grew up believing I could not occupy a feminine position, it’s deeply cathartic to engage directly in this feminized labor. And as a woman committed to social struggle, it is deeply healing, and deeply political, to imagine ways this labor can happen outside the oppressive frameworks in which capitalism has always placed femme labor.

Alyssa Kai of Lupinewood. Photo by Caleb Cole

Alyssa Kai

From a fascist right emboldened by Trump to the waves of evictions in the wake of the Ghost Ship fire, collective spaces of sanctuary, cultural production, and political action are under attack and more important than ever to defend and grow. I came up in such spaces, moving through the constellations of DIY living and performance venues on tour with one

musical project or another, stepping into the lush worlds generated by the activity they housed. For me and countless others, DIY spaces are exceptional places of experimentation that generate microcultures resilient to the challenges of political conflict, and provide points of refuge for people whose identities are under constant attack.

Since we moved in on New Year’s Eve, Lupinewood has quickly become a node for networks of queer and politicized projects circulating around the continent. We have an agency here that many collective spaces don’t have the luxury of wielding: agency over the safety of the space, over the ways it gets used and built out, over the reliability of a future here. Because of this, Lupinewood feels poised to be a particularly powerful and long-running space as both a safe haven for embattled people and a flywheel for the folks and projects that pass through here, whether for a day or a year. And as stewards of this place, we have made a collective commitment to each other: that we will work to keep it that way, in perpetuity.

Noel’le Longhaul of Lupinewood. Photo by Caleb Cole

Noel’le Longhaul

My personal art and tattoo practice grew out of my life as a transient younger punk, not yet having come out as trans, dissociated from where I came from and who I was. Riding trains across the country, I began tattooing elaborate, enchanted houses and landscapes on the transient and often similarly dissociated friends I met, while the literal homes and landscapes around me blurred. I was fundamentally ungrounded, and it took an immense toll on my body and spirit.

Lupinewood is an enchanted landscape. Its architecture is magical; it is thickly wooded and surrounded by wandering paths through the trees, and both the house and the land it sits on mirror the imagery in my work, sometimes uncannily. But it is also an actual place that I wake up to. It gives me the resources I need to regenerate my body so I can continue tattooing and art-making with the intensity that my practice demands.

One of the most crucial—and rare—resources it provides is a shared life with a collective of people who are my partners, friends, and artistic collaborators. The ability to move fluidly between making meals and making art together feels alchemical. It magnifies the meaning of the cultural production, turning a tattoo or a print into an artifact of a shared experience. And it turns daily routines into domestic rituals, which deepen in significance as more people stay here, cook here, receive medicine here, and use this place to ground themselves before making their next move.

beyon wren moor of Lupinewood. Photo by Caleb Cole

beyon wren moor

As a two-spirit mixed Cree and Ukrainian settler now living on occupied Pocumtuc territory, I have no rights in this place called Lupinewood. The white settler promise of “human rights” has never included me or my people, and I know the safeties and comforts promised by such rights are on the same spectrum as feelings of entitlement. For me, Lupinewood is a place of responsibility: to care for the land and the people whose ancestors feed the trees and rivers here.

In the seven months since I arrived, Lupinewood has been a site of security and healing for me, an experience that sits uneasily alongside the knowledge of desperate indigenous struggles elsewhere. Before Lupinewood, and in between living at the Unist’ot’en Camp, Standing Rock, and on other front lines across so-called british columbia, I had been collecting the words and stories of 14indigenous women and two-spirit land defenders. With the help of my longtime collaborator, I am in the process of illustrating, hand-printing, and binding their words into a book describing what land defense looks like in their 14 respective nations. When finished, we plan to sell the book as one of many efforts to support their fight.

I have spent most of my life struggling for indigenous sovereignty and the defense of land, and I intend to use Lupinewood as a point of retreat and convergence for myself and other indigenous land defenders, as well as a tool to rally resources from the relative wealth of this area for front-line struggles.

Nick Berger of Lupinewood. Photo by Caleb Cole

Nick Berger

I’m a non-binary trans artist and musician who’s been living and organizing collectively for the past decade. The punk, queer, and organizing scenes I came up in were vibrant and chaotic, full of glorious aspirations and attempts to combat the massive power structures we recognized as the source of so much violence and pain. Simultaneously, these scenes had strong tendencies toward guilt and self-negation; the people in them were constantly prioritizing action at the expense of their own well-being. We were throwing ourselves at the problems we saw, but there was no space to heal the wounds this inevitably gave us.

As I’ve watched this dynamic happen, I’ve realized that many of us have a deeply internalized sense of disposability toward our bodies and relationships. Living within the capitalist, white, cis-het patriarchy means learning to commoditize lived experiences, and though many radicals are aware of and critical of this, it runs deep. What does it mean to stay in one place, even as one’s trauma catches up to them? What does it mean to consider a set of relationships, beyond perhaps a single romantic partnership, non-disposable? At Lupinewood, I want to work toward reconnecting basic self-care and mutual aid to the labor of organizing work. I want Lupinewood to engage a broader network of collective projects that are genuinely effective politically, and genuinely trauma-informed and care-oriented.

Terran Nullius of Lupinewood. Photo by Caleb Cole

Terran Nullius

I’ve worked with immigrants and refugees for the past nine years. I coordinate a site where classes and counseling services are free to non-native English speakers. These folks create a place together that is beautiful and worthy of defending, even as this country’s political culture turns against them.

We moved into Lupinewood as Trump was getting elected, with his bluster about a border wall and mass deportations. As we started unpacking our boxes here, the national conversation was decidedly about displacement.

Like my classroom, Lupinewood is about the creation and defense of place.

I’m not an immigrant. I’m white, U.S.-born, and live on stolen land. My relationship to place is privileged in many respects. Even with my privileges, finding a secure place has been incredibly hard. Being trans, polyamorous, lower class, and saddled with student debt have all led to years of unsafe, unstable, and ugly living situations for me and so many of the people I’m close to.

I want Lupinewood to create a place for people who more often battle displacement. I want to make it safe and strong, with the ability to offer shelter on short notice. I want to leverage Lupinewood’s privileges into infrastructure to support those who lack it. I want to make it physically beautiful, the kind of space people without power usually cannot access. I want to build a place worthy of defense.

Andrew Huckins of Lupinewood. Photo by Caleb Cole

Andrew Huckins

I believe that architecture subtly defines the limits of what’s possible, whether one is trying to change the world, simply get out of bed in the morning, or both. I’m thinking not just of physical space, but of cultural, economic, political, and social space as well. Whether it’s a local bylaw that recognizes only heteronuclear definitions of family, or the behavioral norms enforced by one’s peers, these architectures define paths of least resistance that lead inexorably toward a broken status quo.

The seven years I’ve spent working to realize Lupinewood have been a practice in forging paths that diverge from those of least resistance, and toward making resistance part of Lupinewood’s architectural DNA. Beyond the particular acts of resistance enacted by our collective and its networks, Lupinewood is, for me, the first major step on a lifelong path of creating, growing, and defending alternatives to the well-trodden walkways this civilization has wandered down.

I see Lupinewood growing into a deep resource for the upcoming struggles that our communities face. Building a kitchen capable of cooking for large groups of people, setting up a communal wood and metal shop, creating space for political organizers and their projects—while these are some of the specific next steps that I’m excited about, I feel most moved by Lupinewood’s broader potential to support, rather than suppress, the wisdom and power of those on the receiving end of systems of abusive violence.