Berkshires composer and former MoMA music director gives voice to three silent films from the mid-twenties

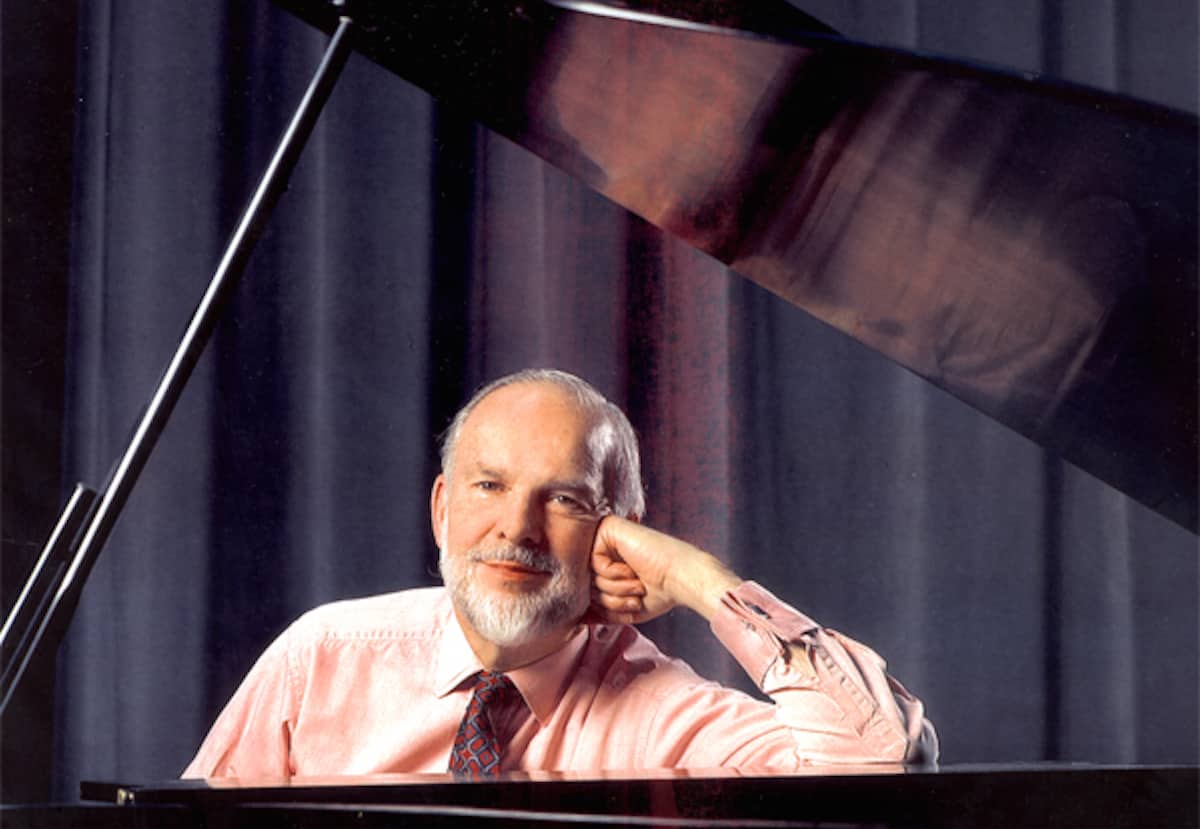

Berkshires composer William Perry has made a life’s work composing for silent films. The Museum of Modern Art’s music director and composer-in-residence for 12 years, Perry spent that time composing and performing music for the museum’s extensive silent film collection.

“I created a large number of scores for silent films and performed them on piano in the old tradition,” he says of his time there, noting silent film star Lillian Gish was a good friend. “I happened along when there was a revival of interest [in silent films] in the late ‘60s and ‘70s. It was a happy coming-together at the right time.”

The Farmington Valley Symphony Orchestra will perform a work he composed for three silent film shorts, called The Silent Years:

Charlie Chaplin

Rhapsodies for Orchestra and Piano. While the orchestra plays, the films — The Beloved Rogue featuring John Barrymore, Blood & Sand with Rudolph Valentino, and The Gold Rush starring Charlie Chaplin — will be screened. Pianist Nadine Shank is the soloist.

“They represent a kind of different challenge,” Perry says of this composition. “The Beloved Rogue with its Middle Ages setting requires fanfares. Blood & Sand has the Andalusian bullfighting thing. Then The Gold Rush combines humor with pathos. Poor Charlie left alone on New Year’s Eve. They’re different enough that it’s exiting to write different styles of music to capture all the color and atmosphere.”

Perry, who in his post MOMA life, among other things, produced an Emmy Award-winning TV series, The Silent Years, that starred Orson Welles and Gish, is a font of silent-film facts.

John Barrymore

Composing for silent films is unique, Perry says. “Because they’re silent, your musical score — piano or orchestra — represents a number of things. It provides mood and period and color. That’s the same thing a modern sound film does, but a silent film score is also providing sound effects because there are none on the screen.

“You’re also trying to catch the mood of jokes or sad moments,” he continues. “You hope you can get there and assist, in a sense, punching home the stuff that’s supposed to be funny and at the same time underscoring the stuff that’s supposed to be more tragic. You’re the only source of sound for the audience.”

Initially, Perry says, much of silent film music was improvised, with pianists following cue sheets for key scenes. “They learned to play danger music, chase music, clown music — cues to drop in and fit the mood.”

Later, in the ‘20s, scores became the norm, Perry says. Pit orchestras performing live music, as the FVSO will do in its performance, were the standard during the silent-film era. Perry notes, for instance, that movie houses in Hartford, Connecticut, likely had five or six musicians during film screenings, while the Roxy in New York City might have an 80-piece orchestra.

“Typically there was more than one score for a film,” Perry says. “Chaplin was a composer himself, so later on he did revisit The Gold Rush and write some music for it. There were different scores for the better-known silent films.”

Rudolph Valentino

Perry is not just a silent film composer. After his MOMA stint, in the ‘70s, he produced a poetry series for PBS called Anyone for Tennyson? It starred, among others, Henry Fonda, Jack Lemmon, Claire Bloom, William Shatner, and Vincent Price. He also produced and composed the scores for the Peabody Award-winning Mark Twain series of PBS feature films. His Broadway musical, Wind in the Willows, which starred Nathan Lane, won him Tony nominations for music and lyrics.

At 85 and still composing — he just finished a chamber piece for viola and piano when we chatted — Perry describes himself as “somewhere between composing and decomposing. My goal is to get up there with Elliott Carter, who was 102 and composing right up to the end.”