Master welder Johnny Swing’s remarkably comfortable coin-based furniture is built for the curves of the human body.

Johnny Swing is a master welder, dairy farmer, sculptor, and somewhat devious poker player. He’ll tell you what’s in his hand just because that’s not the way things are done, then dare you to bet against him. Swing’s work sits beside de Kooning’s, rests on the lawns of the Duke of Cornwall and the Storm King Art Center, and is displayed in Christian Dior stores in Beverly Hills, Tokyo, and Seoul. He’s also a leader in the American Studio Furniture movement, his work considered on par with contemporary masterpieces by Ron Arad and Marc Newson—a position that makes Swing chuckle, feigning complete ignorance. For a former ’80s Manhattan art-kid troublemaker who used to hang with Basquiat, the development of Swing’s art from explosive installation to folk-art avant-garde has been linear, but the thinking that goes into his craft has been as curvaceous as the lines that run through his current work.

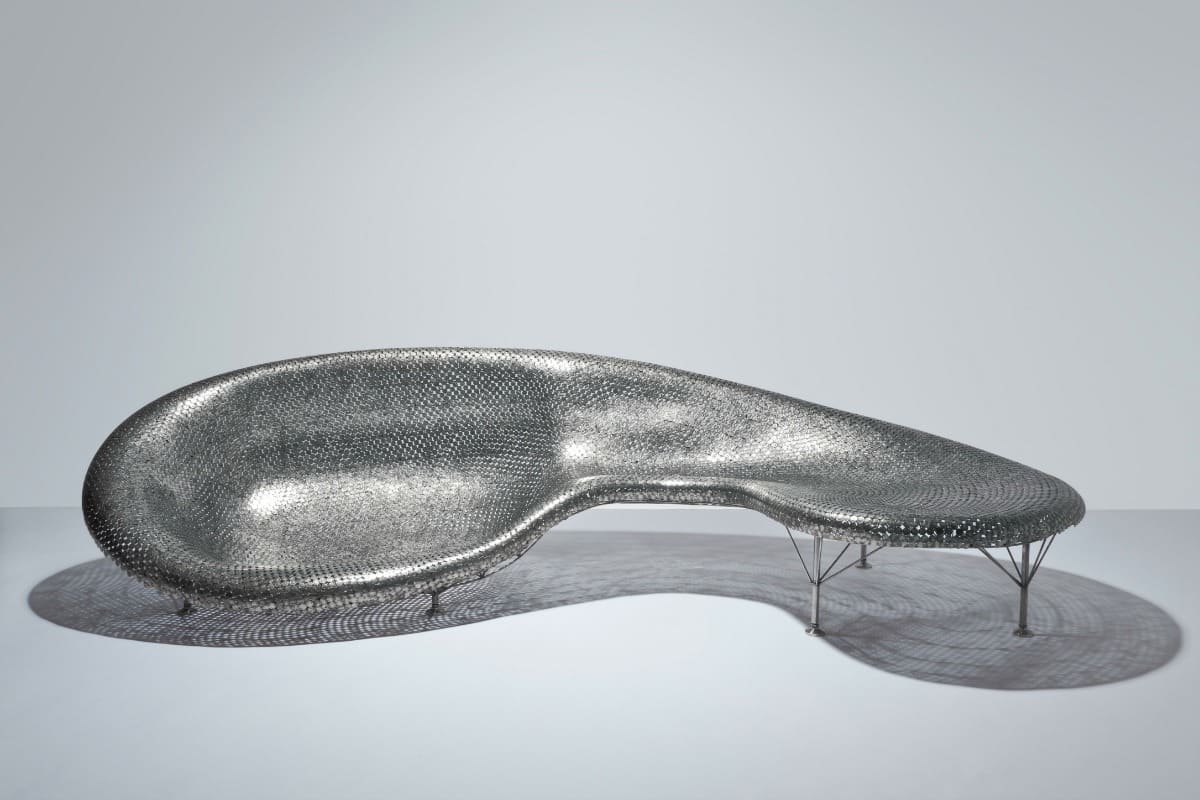

Swing first started making furniture from coins in 1997, with Penny Chair. Using a design based on Harry Bertoia’s Diamond Chair (with legs inspired by Tatlin’s Tower, a tightly wound, constructivist monument designed in 1920), Swing’s initial piece was met with resistance. Consisting of 6,500 pennies with over 30,000 individual welds, the piece was basically a riff on Harry Bertoia’s iconic design. The indifference toward the piece sent Swing back to an actual drawing board, where he conceived his first completely original coin furniture piece, Nickel Couch (2000). With its graceful organic shape and unconventional use of materials, Nickel Couch got traction immediately.

“I’ve always been a sculptor,” says Swing. “My goal wasn’t to make furniture; after Penny Chair I felt defeated. I needed to create my own shape. I thought I was doing something smart—not in a sarcastic way—but taking something from the past, collaborating with the past and adding a sense of brilliance to it. No one got it. But the day Nickel Couch came off the mold, it got picked up by a local paper and went national within a week.”

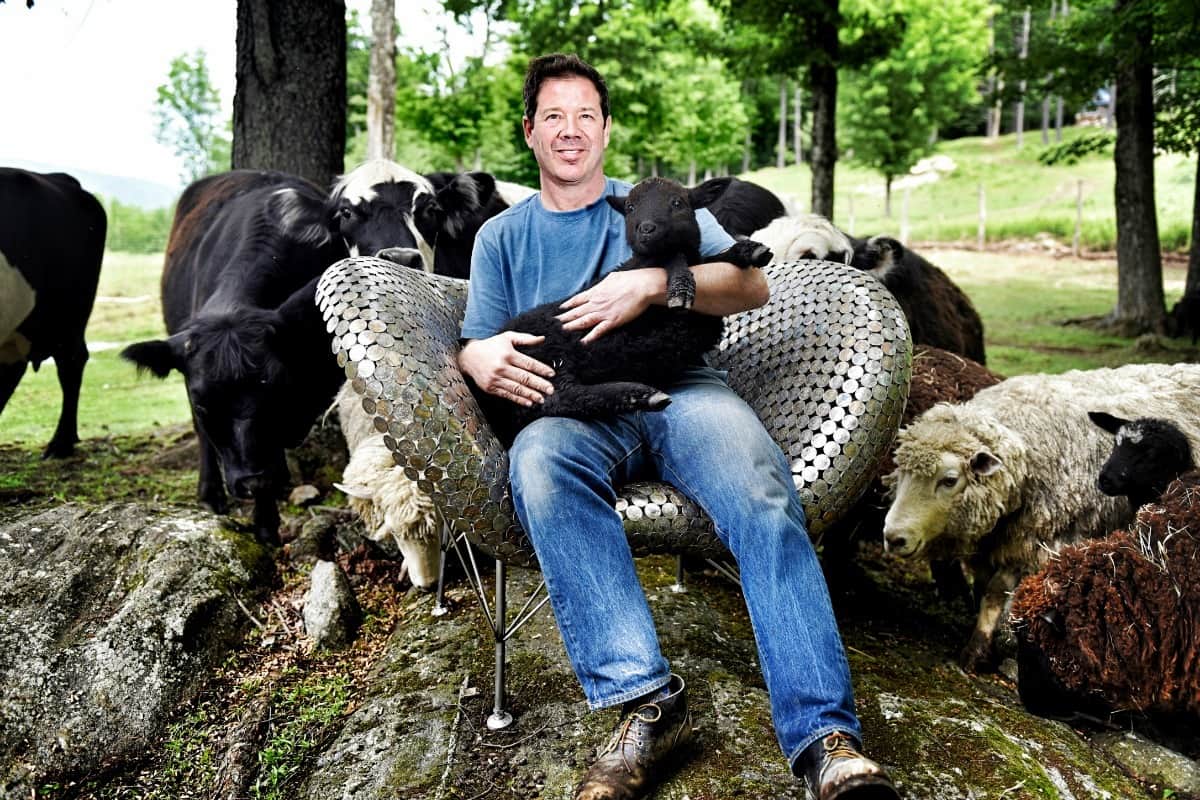

Swing on his Brookline, Vermont, hobby farm, photo by Paul Specht

A Connecticut native, Swing, 56, moved to southern Vermont in 1995 from New York, a city he didn’t find conducive to marriage and a newborn. The family rented, then bought, a 200-year-old house that had once belonged to Swing’s grandmother, a well-known suffragette, in the tiny farming community of Brookline. The setting—a hobby farm with cows, sheep, and chickens—is a stark contrast to the sleek, urban vibe of the furniture he creates in the glass-and-cement studio Swing built a mile away. “I worked in New York City for 13 years,” he says, “and people thought my work was so urban. Now I’m in the country, and all of a sudden I’m a ‘Vermont artist.’”

While his work has been shown in New York, London, Paris, Los Angeles, and Miami, it’s taken 22 years for Swing to have a show in the state where he lives: a solo exhibition at the Bundy Modern in Waitsfield, which ran July 21 through September 17, 2017. A proverbial labor of love, the exhibition featured seldom-seen lamps, built like ominous alien lily pads, that had been in storage for years. “They’re some of my favorite works,” he says. “The lamps are like doodling for me— basically free-form organic structures with a lot of structure inside them. It took an enormous amount of effort to put them up, but it’s valuable to remind myself how much pleasure I got in making them.”

The most recognizable feature of Swing’s furniture, besides the overtly sensual curvatures that run through nearly all his work, is the use of U.S. coinage as the primary physical component. Creating furniture out of pocket change can have a disconcerting effect on the viewer. While the lines of the work are reminiscent of Isamu Noguchi, or maybe an original earthworks drawing by Robert Smithson, up close, the aged dollar coins of his more recent work pull the viewers out of the realm of aesthetic curiosity, and push them into a sociocultural analysis of the work.

Half Dollar Chair (2013) in the Manhattan home of a private collector, photo by Jamie Diamond

“I use old coins because I love the history of them,” explains Swing. “Say a piece has 8,000 coins in it—what’s the least amount of people that have owned those coins? Say 10 per coin: that’s 80,000 experiences locked up in that work. How cool is that? This history of a single piece is just mind-blowing.”

Eventually, the viewer starts to wonder just how much the work cost to build. Swing faces this question every time the work is shown. “Money is way more dynamic than functional,” he says. “A shovel is functional, but are people precious about their shovel? What we’re really talking about are the materials the furniture is built with. [If you’re] using round metal shapes to make furniture—if it’s not coins, the next most logical thing would be a washer. But ironically, you can’t get a washer the size of a 50-cent piece for 50 cents! It all starts with a Yankee mentality of thriftiness—and it’s really funny to think of using coins as being thrifty.”

Nickel Couch, 2000, photo by Jamie Diamond

The other question in this, Swing describes, is whether the furniture is worth more than the coins it took to build it. The question comes not only from people trying to be funny, but also from a place of deep uncertainty, especially when confronted with a couch made of more than 8,000 dollar coins. Compared to the work of Richard Prince or Andy Warhol, whose mastery comes in the form of reinterpreting images, Swing’s work incorporates the literal money itself, setting up a whole other slew of questions and considerations.

“That question approaches a viewer’s insecurity and morality,” he explains, “because [the furniture is] clearly worth more than the money it’s made out of. The fact that people are interpreting the art on that level means they are confronting the value of money, and [the idea] that money has an implied intrinsic value. There’s something beyond my control, in a really positive way, about using money as a medium to work in. Does it put me in a little bit of a box? Yes. Am I the coin furniture guy? Yes. Do I resent it? Sometimes. But at the same time, I feel really privileged that I’ve come up with a way to pose these questions, especially about the intrinsic value of art.”

Penny Chair, 1997, photo by Jamie Diamond

David Eskenazi, an early Swing collector, notes Swing’s instinctive sense of design and raw organic sensibility. “There’s an intuitive level of craftsmanship that goes into the furniture,” he says. “A lot of people are creating biomorphic forms, relying on computer models to develop the shapes, pushing the forms to their extreme. But with Johnny, the shapes all spring directly from his hands, and sometimes a chainsaw. His furniture isn’t symmetrical; it doesn’t fit classical molds of what furniture is supposed to be. It’s not geometric or perfectly symmetrical, but that’s part of what makes [the pieces] so surprisingly comfortable.”

Swing’s gut-level approach is compelling. Going back to Penny Chair, and most notably in Ring Chair and Ring Couch (2012), Swing has developed an ornate arachnid style to his furniture’s legs and backing, none of which is drawn up ahead of time. The backings are completely free form—visualized, then built on the spot without blueprints or instructions. The work appears kinetic, or as Swing calls it, “like the feeling of a cat when it’s about to pounce.” And while the couch might be made of coins or ring shapes, the angular backing is seamless and ornate, like subtleties in an extended jazz composition, adding depth and signature to the work instead of being a mere pedestal on which it stands.

For a master of the American Studio Furniture movement, organic lamps, chairs made of glass jars, and coin-centric couches might very well be the heart of Swing’s work, but his fixation with currency and response to it as craft material sometimes moves from eccentrically sensual to truly disconcerting. In addition to building stuffed animals from paper currency, Swing stitched together a rug in the shape of an American flag (Dollar Bill Rug, 2017), which was exhibited on the floor of his New York gallery, R & Company. Even though Swing testified in front of Congress in 1994 under the Visual Artists Rights Act regarding the eventual destruction of one of his installation pieces, he considers Dollar Bill Rug less a political act and more a performance-art piece. So is this new direction a shape of things to come? “I don’t foresee the work getting more and more pointed. I think it’s going to keep its rounded edges,” Swing says, gesturing to a half-built dollar couch. Then again, he’s a hell of a poker player, so with Swing you never really know.

For more images from our shoot at Johnny Swing’s studio, visit our subscriber-only gallery.

Johnny Swing–furniture maker

Brookline, Vermont

Website & Gallery

Facebook

Instagram

Top image: Murmuration, 2012, welded nickels and stainless steel; 32.5 × 132 × 55 in. Photo by Jamie Diamond