Working for decades with established and emerging artists, Hinsdale’s master printer cranks out fine art at Wingate Studio.

Looking at the building that houses Wingate Studio’s impressive collection of meticulously maintained vintage printing equipment, it’s hard to imagine the business could exist anywhere but New England. Inhabiting a converted barn on a 55-acre family farm that practically straddles three states from its location at the convergence of Vermont, New Hampshire, and Massachusetts, the 31-year-old print studio could double as a stage set for The Crucible.

Wingate Farms

Wingate Studio founder Peter Pettengill’s family has occupied the land for generations. His parents still live in the old farmhouse and his daughter, Olivia (along with partner Susie Parke-Sutherland), has revived the land back into a working farm that grows spinach, flowers, and summer greens, and is home to 900 egg-producing chickens and 8 pigs. A dog named Busy keeps things in order.

For a seven-year spell, however, Pettengill lived in San Francisco, where he attained the title of master printer at the city’s distinguished Crown Point Press and met his wife Deborra before returning back east to found his Hinsdale, New Hampshire studio. It was also where he met many of the influential artists he’s worked with over the years, including Sol LeWitt, Joan Jonas, Wayne Thiebaud, Ed Ruscha, and Elaine DeKooning.

“In the early days I was doing mostly contract printing for other publishers, especially the Limited Editions Club in New York,” Pettengill says. “My very first project here was printing Robert Mapplethorpe photogravures for them.”

Pettengill began publishing independently in the 1990s, producing work that was featured prominently in a 2015 30-year retrospective curated by Boston University, including prints by Xylor Jane, Chuck Webster, and Sebastian Black. Jane, a Greenfield, Massachusetts-based artist whose process he describes as “translating notions of time, meaning and pure mathematics into her own visual language,” is a mainstay with whom he still works with some frequency.

Wingate publishes printed editions of work it creates with both established and emerging artists who are invited to print at the studio. While specializing in intaglio etching, Wingate sometimes works beyond the usual bounds of this process according to the needs of the artist. The artist guides the project; the studio facilitates. The resulting prints are then promoted and marketed by Wingate both to private clients and institutions, including the Whitney, MoMA, and the Library of Congress.

When pressed, Pettengill singles out avant-garde legend John Cage as a favorite collaborator, who he recalls as “one of the most inspiring people I ever met, a very disciplined artist in spite of his famed reliance on chance operations.

“His approach was to imitate nature in her manner of operation,” Pettengill continues. “So he set up systems that would use chance to create strikingly beautiful visual work. He didn’t separate art and life, but continually showed how they were one and the same. His joy and pleasure in the ordinary aspects of life were absolutely contagious.”

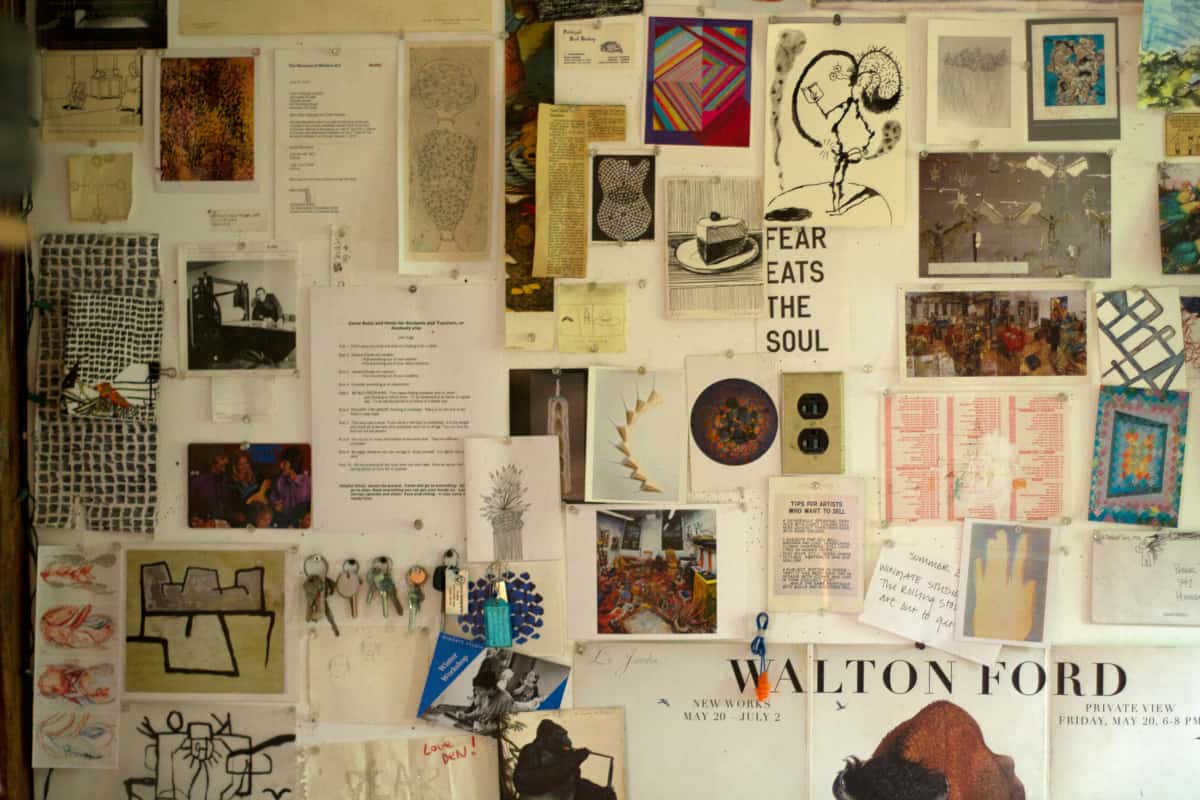

Inside wall of Wingate Studios

Wingate is a place where artists can come to focus intently on a particular creative goal, living on the farm or in nearby lodging while immersed in a weeks-long project. The property isn’t impossibly far from New York City, however, so the studio does also attract the odd commuter, like painter Walton Ford, who might be up two days a week to keep a project rolling.

Known for his life-size watercolors of birds and animals in the style of 19th-century natural history painters like Audubon, Ford’s work is, according to Pettengill, “visually stunning and appealing,” but also bears “a large element of the grotesque.”

“His paintings and prints create complex narratives, often based on historical events or people, and function as critiques of the general human enterprise, exploring themes of colonialism, industrialism, the environment, extinct species and crackpot explorers and adventurers. It functions on many different levels, but it invariably draws viewers in before they have a chance to comprehend the breadth of it.”

Despite the somewhat arcane nature of the craft and (by today’s standards) an antiquated pace of distribution, Pettengill believes that print has a bright future thanks to interest from younger generations of artists. His son James and James’ wife Alyssa, who function as studio co-directors, have also brought a more modern edge to the business.

“They keep up with and are connected to today’s emerging artists, and they’ve really pushed Wingate forward in terms of our publishing program,” he says. “We have been working with a lot of younger artists over the last couple of years.”

In fact, he believes the art is flourishing, both through traditional outlets and via workshops affiliated with colleges and universities.

“We’re also in a moment where artists are working across media more than ever, not limiting themselves strictly to a painting practice or even material media. They’re interested in doing their work in many different forms, and, of course, there are so many new technologies that are carrying printmaking into the digital age.”

Peter Pettengill at Wingate Studios