Sculptor and architect Mohamad Hafez uses detailed miniatures to create a visual lament about the Syrian war.

Mohamad Hafez papers the walls of his New Haven, Connecticut, studio with printouts of news photos. The pictures show old women weeping and gesticulating; piles of rubble in narrow, ancient streets; young boys with a look of shock and sadness on their faces; rows of tanks; views from inside blown-out interiors; half-demolished apartment buildings; and throngs of huddled refugees awaiting food or rescue. The photos are from Syria, Hafez’s birthplace.

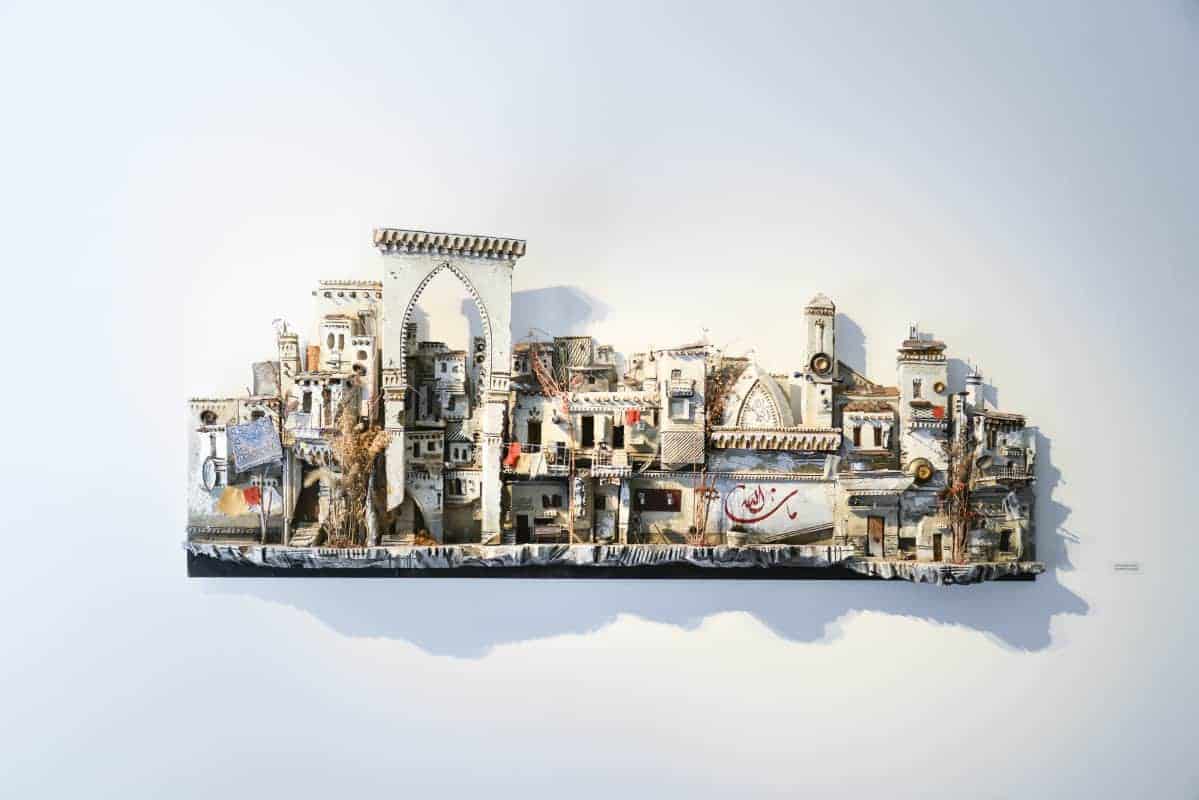

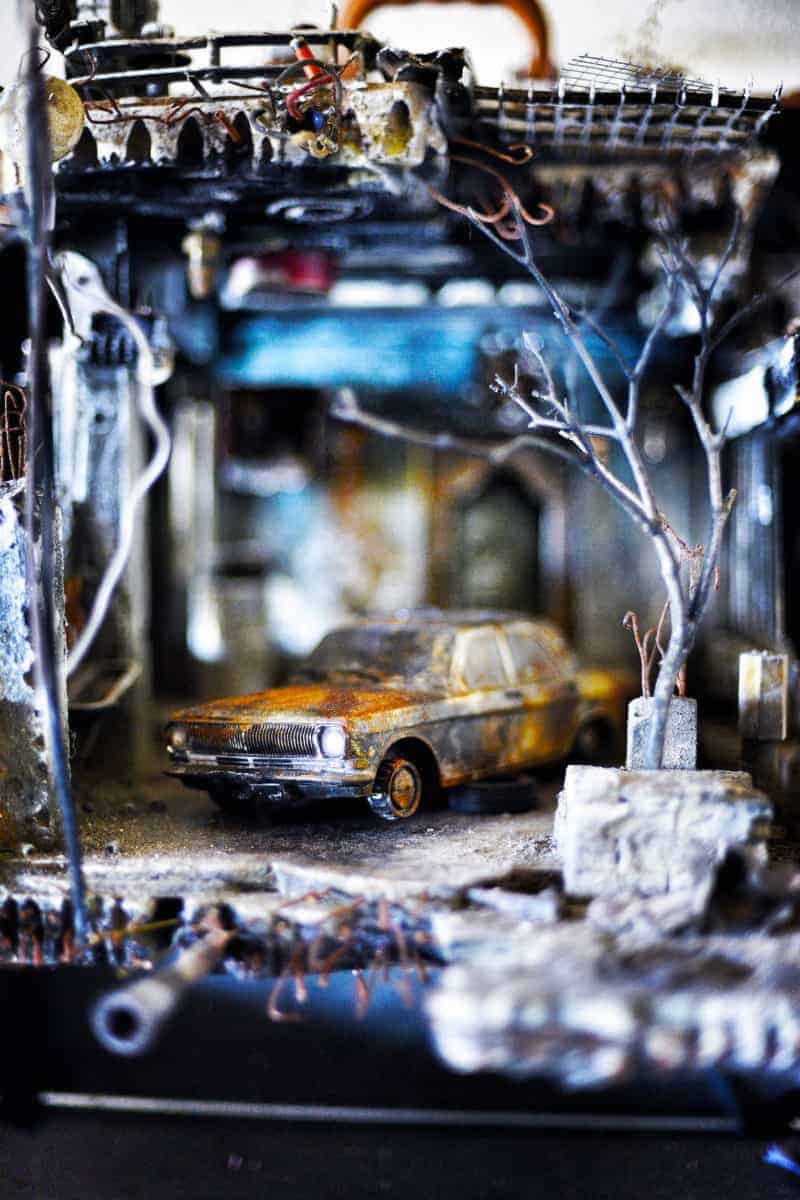

Hafez, 33, works as an architect, designing corporate high-rise skyscrapers for Pickard Chilton. That’s his day job. But in the evenings, on his off-hours and often late into the night, he comes to work on his visual art in his upstairs studio in the Westville Village Historic District section of New Haven, a few blocks from the Beth El–Keser Israel synagogue. Hafez makes detailed assemblages—scale models and sculptures—that generally hang on a wall. Many of Hafez’s pieces depict ripped-apart buildings, with dangling wires, bullet-riddled plaster, and crushed furniture. They’re like dollhouses that re-create the destruction of war rather than the comforts of domestic calm. Others are part of what Hafez calls his Baggage Series, which he makes using open suitcases of varying sizes, crammed with miniature items, sometimes including numerous tiny houses or fragments of dwellings.

Mohamad Hafez considers Unpacked Refugee Baggage: Ayman & Ghena, 2017, mixed media. Photo by Paul Specht

When he was 19 years old, enrolled as a first-year student at Iowa State University, Hafez took some of the skills he was learning in his architecture classes and eventually started applying them to intricate models of buildings from Damascus. The hobby served to ease his homesickness at the time. This was in 2004, before the civil war began in 2011, in which over four hundred thousand Syrians have died. This was before the humanitarian crisis that sent approximately one million Syrian refugees to Europe.

Having entered the United States with a one-time entry visa following an extensive background check, Hafez feared that being a Muslim from Syria named Mohamad might make reentry into the United States unlikely. So, for about seven years, Hafez channeled some of his longing for home and family into work that conjured Syria. As an architecture student, Hafez was understandably drawn to the layers of history and culture represented in the buildings of Damascus, with their meshed and stacked traditions and

aesthetics—Islamic, Byzantine, Roman, Hellenic, modern, and more. When the civil war began, Hafez, watching reports on TV and online, saw the material destruction as emblematic of the senseless human suffering that went along with it.

His artwork is a sort of visual lament. “There’s the personal component of this, in the sense that I am weeping over the death of my country and culture,” he says. “Well, how do you cope with that? How do you cope with thousands of years of culture and heritage and archaeological sites being bombed into dust in front of your eyes in a six-year vicious war, without a meaningful outcome being planned, or at least a light at the end of the tunnel? As a Syrian, as a Muslim, as an Arab, how do you cope with that while living in the diaspora?”

Hafez is quick to establish that his suffering—reading about the war in Syria and watching news reports from halfway around the world, agonizing from a distance—is nothing like that of those who are there. But, his predicament offers a peculiar kind of vantage point that increases the sting in some ways.

“To see your country deteriorate and see the whole picture from afar—that’s another torture in itself. Because when you’re in it, you’re just consumed with your day-to-day life,” he explains. “But when you’re outside of it, you get more of the whole big picture. You’re getting a taste of so many medicines. So the only way I figured I could cope with that was to get into these models, these sculptures.”

Hafez got to go back to Syria in 2011, right before the civil war erupted. But he hasn’t returned since. He says he’ll go again when things calm down.

Mohamad Hafez, Unpacked Refugee Baggage: Um Shaham, 2017, mixed media. Photo by Paul Specht

One could, theoretically, look at Hafez’s sculptures without any knowledge of his background or the specific subject of the work, and assume that the artist was somehow making Joseph Cornell-esque assemblages that aestheticize destruction or structural decay. Hafez recognizes the impulse, but it doesn’t motivate his work.

“I do surround myself with photos of the destruction just because . . . it’s not beautiful . . . it’s sophisticated,” he admits. “Destruction in itself is sophisticated, and the detail attracts you. There’s a sad and horrific component to it, but the way that buildings fall apart and the rubble, to the human eye, is mesmerizing. I don’t know why. Our dark side likes seeing things dismantled. It’s curiosity. My job is to remodel that curiosity and to tell you there are human beings living in there. So you see the laundry lines, you see birds’ nests, you see different hints of life that take place.”

Art is supposed to expand our sympathies. Hafez’s work can spur viewers to feel their way into a routine life—a mundane life, with clothes, dishes, furniture, houseplants, and neighbors—that has been upended and blasted apart by hostile, chaotic, and indifferent forces. Sometimes there are pieces of Koranic calligraphy spray-painted on crumbling facades. The phrases are inspirational, hopeful messages for believers, about justice and perseverance, but they also have the visual hint of revolutionary signals—as if simply surviving and retaining dignity were a kind of insurrection in the face of war and bomb blasts. Faith is almost seen as a form of defiance.

If he’s summoning chaos and dislocation in his work, Hafez finds a way to that place in his carefully ordered studio, playing the sad but meditative Persian violin music of Kayhan Kalhor, working into the night in a kind of trance. Neat bins and boxes of found objects are separated: driftwood here, plastic there, rusted metal in one container, shiny fuses in another. Glue guns and tools are stacked and arranged. Hafez doesn’t create in a jumble, even if what he creates resembles one.

Bricolage—art created by assembling media from multiple sources—is usually slightly crazed and off-kilter, but Hafez’s constructions have a strange obsessive realism. Hafez’s day job as an architect gives him a built-in sense of material and scale that contributes to the authentic feel of his war-torn miniatures and the substructures that get pulled into the light when a building is destroyed.

“You’re always trusting your artistic intuition and your architectural intuition,” he says, “in that if you’re modeling a building, you’re thinking ‘Does that look right? Is the thickness of the slab, the thickness of the wall, the proportion of the window to the floor, correct?’ That’s subconscious at this point. Because when you break a wall you expose rebar; when you break a floor you expose electrical and plumbing.”

When he’s designing corporate high-rises at Pickard Chilton, advance planning is central. But his visual art allows for much more spontaneity and freedom. Hafez might even be said to be improvising space.

“In my day job, we design every bit of detail in our architecture projects,” he explains. “When you start, you have a pretty darn good idea of where you’re headed. This work is so liberating in the sense that I just start building, making on the spot. If it looks right, fine; if it doesn’t, I’m ripping that off and throwing that on the floor.”

Hafez’s work has been shown around New England and the United States, as well as in the United Kingdom. A recent show at New Haven’s Artspace featured a collaborative series of pieces from Hafez and Ahmed Badr, an Iraqi-born writer who is now attending Wesleyan University in Middletown, Connecticut. Together, the two interviewed refugees from the Middle East, Africa, and Afghanistan, collecting their stories and documenting their accounts of war, uprooting, wandering, resettling, and longing for home. The show, UNPACKED: Refugee Baggage, is a multimedia effort to humanize and individualize large-scale events that often get covered from a distance, or lost in the charged political debate in the United States today. Audio clips are woven together with Hafez’s constructions. The artists hope to redefine and expand the meaning and associations of the word refugee in twenty-first-century America.

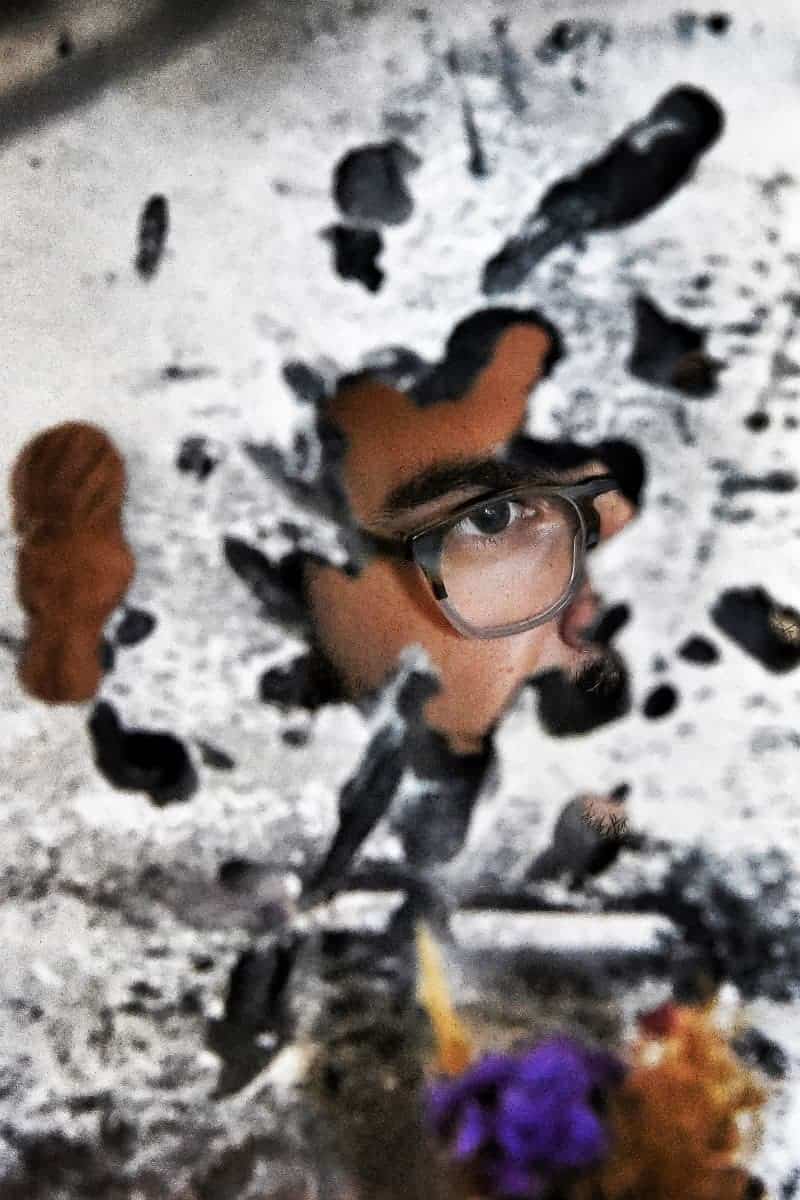

Mohamad Hafez. Photo by Paul Specht

To create his work—to make it with the right force—Hafez feels like he needs to channel some of the suffering. “I feel a responsibility,” he says. “If I want that emotion to come through honestly in the work, then I have to be that emotion for that amount of time and put it in the work.”

The keening instrumental music on the stereo helps him focus. Hafez says he “latches” with it. “First what I’ll do is look at a lot of photos. I look at what happened—I remind myself,” he describes. “I look at the photos of kids, of refugees, of dead people on the streets, of our devastation, in order to absorb that and put it into sculpture.”

Mohamad Hafez

New Haven, Connecticut

Website

All photos by Paul Specht