Justin Squizzero and Eaton Hill Textile Works painstakingly create gorgeous, historically accurate, textiles in Vermont.

Period pieces are incredibly trendy right now. No, really. Netflix is awash with notable actors gliding around million-dollar sets of Buckingham Palace and Renaissance-era Florence. Hollywood is churning out critical darlings like The Witch and Silence. Hamilton has revolutionized Broadway. Even HBO’s record-breaking sci-fi masterpiece, Westworld, revolves around our collective nostalgic thirst. Joyfully, dedication to historical accuracy plays a critical role in the success of productions like these. It has been a boon to artists and designers who’ve mastered historical techniques that have been long overlooked. It should surprise exactly no one that New England is home to one such artist: Justin Squizzero and his fellow weavers, dyers, and upholsterers at Eaton Hill Textile Works in Marshfield, Vermont.

Justin Squizzero

“It was one of those historic crafts that I could foreseeably do, as opposed to building a blacksmith’s [shop],” Squizzero says of his start in weaving, “My family was involved in historical reenactments; the idea that this was something people did was not foreign to me.” This explains why he’s the youngest weaver’s at Eaton Hill, and youngest teacher at the accompanying Marshfield School of Weaving. The school was started in 1974 by Norman Kennedy, a Scotsman who learned weaving from the last of the British handweavers after World War II. Kate Smith began studying under Norman in 1976; it was she who taught Squizzero before she officially re-opened the school in 2007.

Marshfield School of Weaving and Eaton Hill Textile Works are intrinsically tied to rural Vermont, as the institutions rely on their unrivaled collection of authentic 18th- and 19th-century hand looms. “The frame is the same as [an 18th century] house or a barn—it produces a very sturdy piece of equipment,” explains Squizzero. They take around two hours to thread, but once there’s an experienced weaver at the helm, they can produce about a yard of fabric every 45 minutes. “We do small orders—small batches of dying. It’s appealing for people who want to buy a small amount of very unique fabric for, say, one piece of furniture.” Production of the fabric starts by sourcing historically accurate yarns and worsteds—locally, if it can be accommodated. Eaton Hill does all its own dyeing, and Smith has a sample library of every color she’s ever produced, complete with recipe, that’s over 30 years old. According to Squizzero, “It’s probably the most valuable part of the enterprise.” The majority of work Eaton Hill receives is from museums and historical sites who need either specific colors, or, harder still, exact matching replicas of upholstery or rugs.

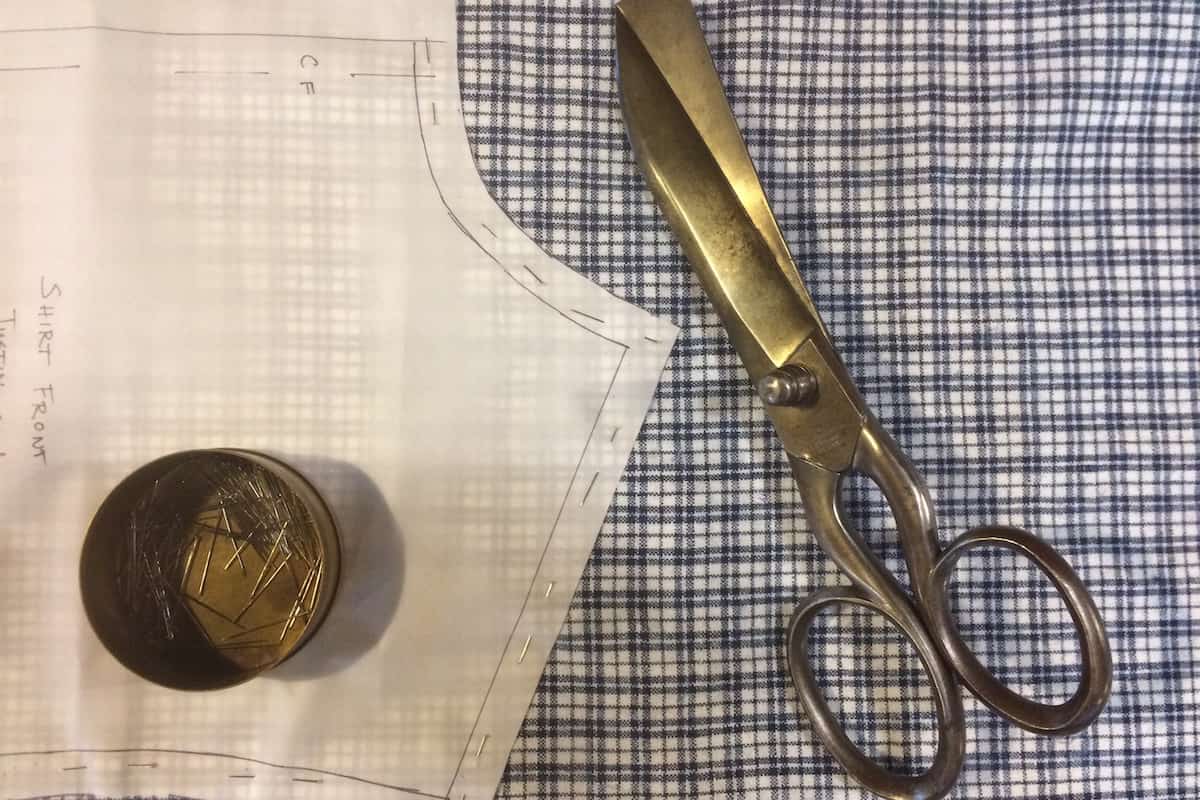

Eaton Hill Textile Works | materials | Photograph by Justin Squizzero

Eaton Hill was commissioned to do a custom stair carpet for Dumbarton House, a Federal-era mansion museum in Washington, DC. Squizzero cites the project as one of his favorites, because the research involved thumbing through some fascinating 18th-century artifacts. “We chose a design from a weaver’s notebook from Connecticut,” he says. “It has some of the first, if not the first, American carpet designs. People don’t expect it, but it could be made here—and it was! [The weaver] gives the color names and number of threads for production.” Ah, but how to know if the finished result is historically accurate, when there’s no picture or sketch? “When the weaver from Connecticut said ‘orange,’ it could mean anything,” Squizzero explains. “But there’s this book at the MET in New York, a dyer’s manual from the 1820s or teens, and he dyed a sample of each recipe and placed a sample inside the book so they’re preserved.” So take heart, fellow history buffs: we can still know exactly what orange looked like during the first Adam’s administration.

Dotted along the Eastern seaboard are a handful of historical sites that now contain Squizzero and his colleague’s work, including George Washington’s Mount Vernon, Colonial Williamsburg, James Madison’s Montpelier, several Federal mansion museums in Philadelphia, and even some Antebellum plantation museums in the Upper South. Eaton Hill also does contemporary work, from unique furniture upholstery to custom table linens. But for Squizzero, the work is more important than the project. “Much of the agrarian history of Vermont fits into a whole different way of working and living,” Squizzero says. “The people who were [weaving] in Britain were cranking out yard after yard, but the people in New England were doing it for homewares and farm work. It’s a nicer pace.” Much about what Eaton Hill represents is a commitment to quality that simply can’t be achieved with modern-day production methods. The integrity of the craft is what defines its luxury.

Justin Squizzero Weaver Loom

Eaton Hill is the only mass producer of authentic 18th- and 19th-century textiles in the country, and Squizzero says business is always good. “The equipment we use and the techniques we use is a constant—it will always be these 200-year-old hand looms. For me, the fabrics are completely interwoven with this culture and place, and our identity. It’s authentic and genuine in a way that I always want to work in.”