Casey Spectacular paints, performs, and writes to illuminate how our specific histories inevitably inform personal mythology.

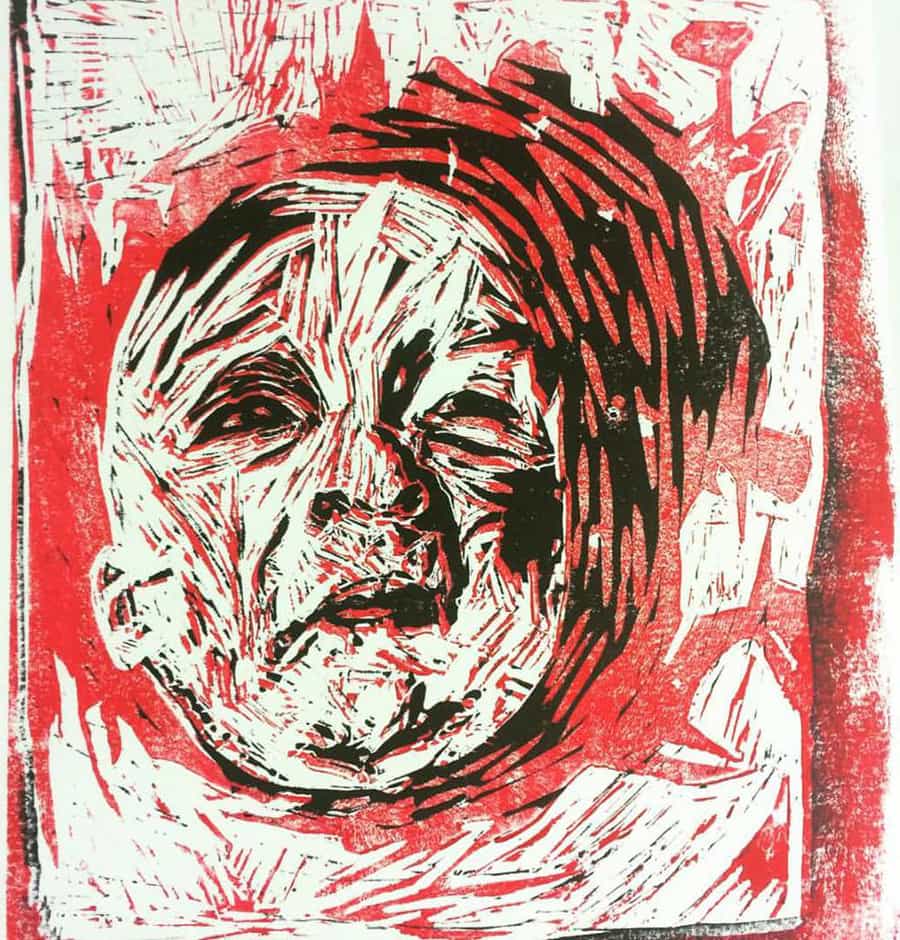

Casey Spectacular’s art breathes with the stained humanity of a life pulled through cigarette filters: the works cry, wrinkle, cough, and pustulate, occasionally smiling with lopsided lips and browned teeth. The characters who appear in his work are varied, often very old or very young, and usually suburban: in the collection I Used to Be a Dancer it is a friend from art school—a first generation Chinese immigrant depicted as a child in a series of awkward dance costumes; in “Suburban Dreams,” from the collection Connecticut, they are three white men in athletic gear embracing one another and giving a thumbs up in the parking lot of a Cumberland Farms. In others, they are distorted babies, female serial killers, and drag queens.

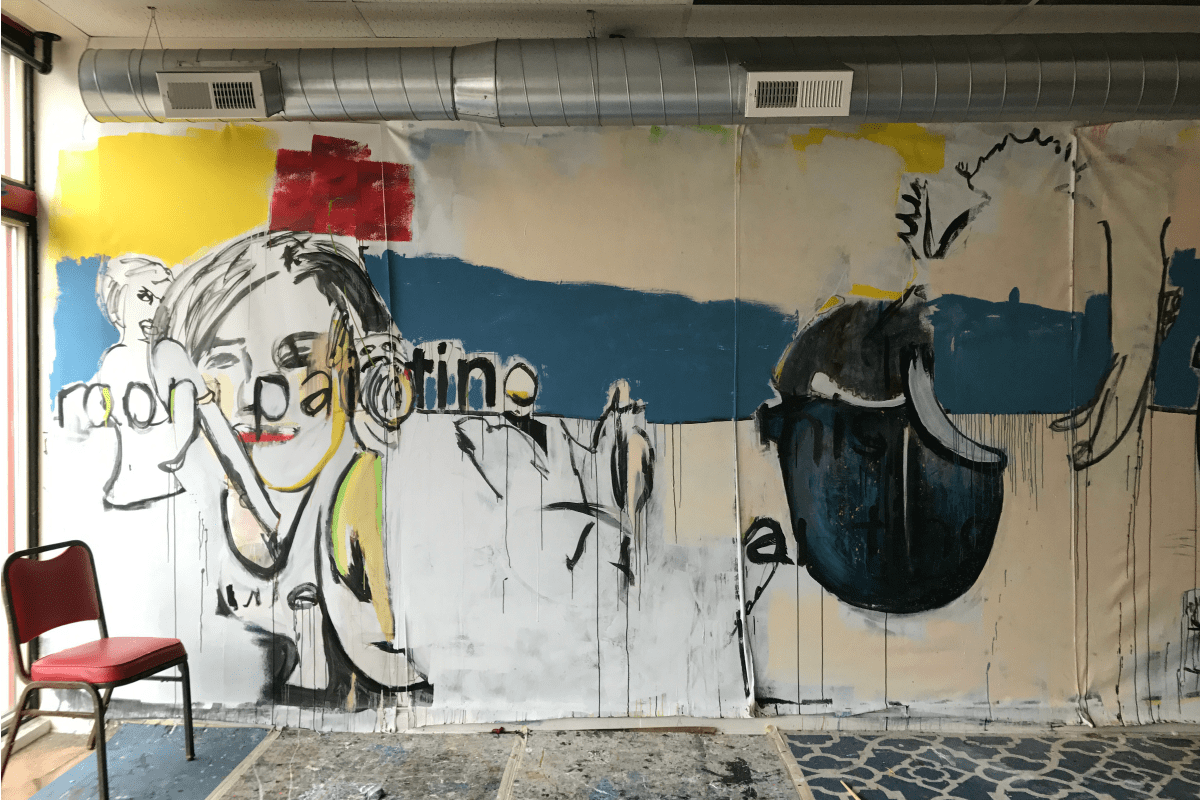

Wanda Jean Allen, These Women Are Dead series | Photo courtesy the artist’s website

“I think I am a visual artist, but they’re more illustrations,” he says of his work. “I’m really into storytelling, I think that’s where it’s at. Humans create drama, and that’s really cool to me.” Spectacular produces paintings most frequently but also outputs video and performance, as well as an upcoming novel.

Frequent motifs across mediums include parents, bodily fluids, and bad skin. Some works elicit embarrassment, often humor, sometimes fear, and all bare grossness as an ever present qualifier to life rather than an infrequent extreme. It never feels vulgar, nor do the gross details ever mock their subject. Their inclusion feels presented as an act of love for these sorts of characters, a way of presenting people as they are, unfiltered.

When Spectacular shows his paintings in galleries, many viewers respond with repulsion. “I don’t think there’s anything shocking about them,” he says. “People hate seeing crying babies or an old person’s veiny hand but it’s important to see these things as beautiful. They’re real stories.” Teenagers in particular, he says, seem to really relate to it.

Poor Casey

Spectacular’s art is largely concerned with themes of growing up, and the dynamics of the families we are born into as well as the families we find through culture. The youngest of four siblings in Norwich, Connecticut, Casey’s youth was spent surrounded by the teenage drama of his older family members, a facet of adolescence he has come to embrace as humorous and human. When he went to MassArt, he found familiars among the artists and goofballs in Boston’s punk and drag scenes. Though never feeling fully a part of either, these cultures exposed him to creative communities as well as ideas of performance and rethinking cultural symbolism.

Although many of the motifs in his work reflect those of his life, Spectacular says that the art is never really about him, but rather that the stories serve as a personal mythology: he is less interested in exploring the specifics of his own experiences than he is in a grander arc parallel not only to his life but to the lives of others. He says there is an element of folk art in how he focuses on the ways people from this area construct their worldview and how different lives react to living here.

Confusion

“When I was a kid I had a way easier time connecting with mythology than church. That was the only way I understood religion,” he says. “The idea that gods had personal drama that shaped everything – It made sense to me.”

Casey’s next project, Queef: A Novel, follows a young person in southern Connecticut as he grows out of an unwanted youth and begins to find value through his first encounters with queerness, drug use, and meeting the kinds of people they tell you not to spend time with.

On August 12th, a show will open to coincide with the completion of the book at the Hygienic Gallery in New London. It is a presentation of moments and details from the novel featuring stylized excerpts and illustrations from Casey and 26 other artists.

A painting of the novel’s main character wears a secondhand gym uniform with the collar torn so that it hangs of the teenager’s shoulder. “The shirt was real. If we couldn’t afford new ones the school gave us secondhand ones, and of course I’m like the only gay kid in the school and I got the one that hangs halfway off my chest.”

Casey likens the shirt to a natural symbol of New England outsider mythology, “It was perfect, I had to put it in the writing,” before adding, “but the face came out too pretty and I don’t know how I feel about it. I’m not sure I like it.”