Portland’s brick walkways showcase the memories of its everyday citizens, creating a new, more inclusive city history.

Based in the India Street neighborhood of Portland, Maine, Portland Brick is a collaboration between storyteller Elise Pepple and me. The project celebrates the everyday stories of the city’s residents. Historic, contemporary, and “future” memories are stamped into bricks that repair sidewalks with the city’s own stories. Instead of commemorating the famous “fathers” of the city, our project highlights the immigrants, the women, the marginalized, the voices that typically are not heard. We aim to rewrite the historical narrative that too often upholds the values of the privileged, rather than telling the real stories of the people who lived there.

An area that boasts the first street settled by Europeans, the India Street neighborhood of Portland, Maine, was originally mostly residential, before becoming mixed-use (business and residential) and falling into economic decline in the mid-twentieth century. Over the past few years, it has been undergoing massive gentrification, with new, upscale restaurants and luxury condos taking over what were abandoned lots. Historically, it was an ethnically and socioeconomically diverse neighborhood, home to African Americans and people of Irish, Jewish, Italian and other European heritage, some of whom were involved in antislavery causes.

The challenge for us became how to create a more personal vision of a neighborhood through Tweet-length phrases about human connections. Making stories tangible as physical objects gives them a new life and a new importance. Some stories will shift from being a story told within a family circle to one that inhabits a public space, while others contain long forgotten facts that will be revived from the dead. We hope that the bricks will generate a new cycle of audio stories shared between strangers, friends, families, and visitors.

Through local organizations, online submissions, historical research, and the efforts of Maine College of Art students, Elise collected stories that often came in multiple forms. Fragments of gossip, oral interviews, newspaper clippings, and historical records all contained information that on first impression might seem dry and generalized but was rich in narrative below the surface. Through a storytelling event in the neighborhood, a TEDxDirigo talk, and through social media, we have been able to further connect with residents.

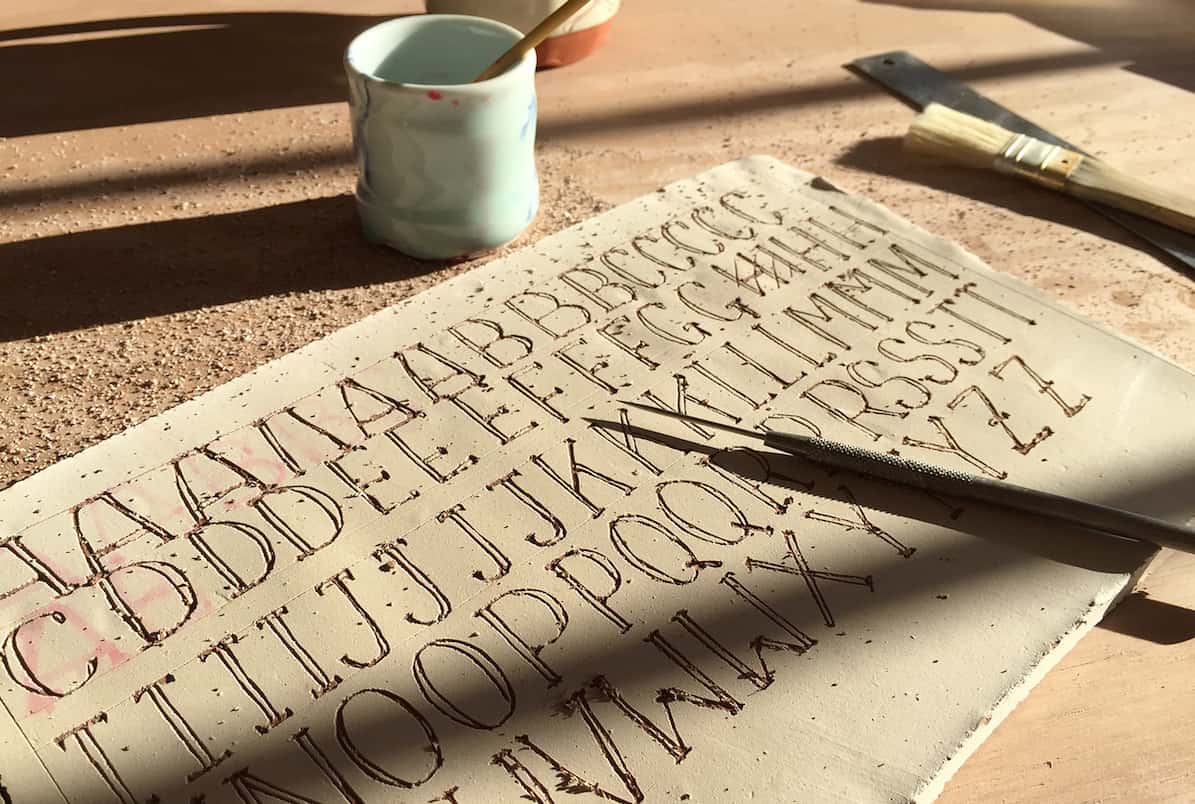

Horie drawing letters using the sgraffito technique | Photo by Ayumi Horie

We walk to work on brick sidewalks, we build our homes beside them, we live our lives on them. I love the alchemy of transforming the ground beneath our feet into the brick beneath our feet. Fifteen thousand years ago, at the end of the last Ice Age, Maine was covered by a glacier. As the ice retreated, it pushed down the coastal shelf, flooding the southern shoreline of Maine and depositing a layer of mud, hundreds of feet thick in some places, above and between bedrock. This layer is what Portland is built on, and it’s a city largely made of brick.

The clay used for this project was saved from the excavation of the land that my new studio was built on, and is commonly called Maine Blue Clay. After the Great Fire of 1866, most of Portland and its sidewalks on the peninsula were rebuilt with this clay. I considered carving the words into clay and the now-common practice of using water jet methods on commemorative bricks, but these techniques felt too harsh and would under-utilize the beautiful plasticity of clay. I wanted to retain the puffiness of soft clay in the fired brick. The appearance of stamped clay, on the other hand, has always reminded me of flesh pressed down by a finger or the shape of a pillow after a head has rested on it. I wanted these bricks to show that they were made by people, full of tiny imperfections and the unevenness of the human hand.

To make a custom stamp for each brick, I first drew letters using the same sgraffito technique that I use on low-fire pots: I poured white slip onto slabs of nearly bone-dry earthenware, then scratched through the slip with a sharpened pin tool. I drew the letters in different sizes, scanned them into Photoshop, and cleaned them up. Next, I typeset each stamp. Sam Richardson, a recent graduate of the New Media department of Maine College of Art, converted the stamp images into 3-D files, then milled and printed them at Engine, a nearby fab lab.

Rochelle Garcia, Molly Spadone, Janine Grant, and several other students helped fabricate the bricks. After slaking the bone-dry clay, they blunged in red grog to help with shrinkage and warping, and then sieved the mixture. Using David Peters’s method of drying slurry in wooden frames lined with bed sheets outside, they wedged the clay. Traditionally, bricks were made using a sand-struck or water-struck method, where soft clay was slapped into wooden molds that then released the clay. After a lot of trial and error, we found that the simplest of methods was the most effective: we threw a ten-pound block of clay into a thick plywood mold reinforced with clamps, and then unscrewed the clamps to pop the brick out.

A Portland Brick freshly stamped | Photo by Ayumi Horie

We wanted each statement to refer to contemporary digital culture. We wanted our stories to be as brief as a Tweet and as succinct as an Instagram caption, so that they would read like poetry—and fit within the bricks. Using hashtags was a way to insert more information and sum up the phrase, and we liked their playfulness. Of course, the bricks’ hashtags would not work as hyperlinks, but they could be Googled, because the full phrases are also on our website. For instance, the sentence “On this spot in 1911, mothers could pick up free fresh milk for their babies. #pasteurization” provides just enough information to pique curiosity about the history of public health and the importance of pasteurization. The hashtag also connects our brick to every other online reference to pasteurization. Other hashtags include #torrone and #panettone (Italian sweets) #redhotdogs, a classic Mainer food, and #newmainer, a term that’s intentionally inclusive. One bilingual brick reads, “On this spot in 1898, Jun Sing operated one of the first Chinese laundries #goldmountain #金山”. In this instance, the hashtag works from an insider’s point of view, being the moniker that Chinese immigrants gave to America in the nineteenth century.

Rather than use the stuffy, formal language endemic to traditional monuments, we chose to use vernacular wording more in line with those we want to honor and the contemporary audience that we want to affect. With the sentence, “On this spot in 1956, Priscilla and Loretta’s shoes could be heard click-clacking on their way to church,” we hoped to evoke a specific image and a second sense in order to paint a more holistic picture of the neighborhood. (India Street was a fairly noisy neighborhood because of the nearby railroad tracks and the Crosby Laughlin Foundry, which manufactured heavy marine equipment.) “On this spot in 2014, 1 snowy owl took up residence #grandtrunkrrblg #pigeonsupper” reads another brick, the number “1” being a less formal, more appropriate solution than “one.” Composed in the great tradition of Twitter and Instagram, #pigeonsupper connotes a well-fed owl.

Composing each phrase was a linguistic challenge that Elise and I worked on. Which word would stand alone, which word or words made large? What might catch someone’s eye as they walked down the street? Among the largest words are “lost,” “elephants,” and #celebrates.” Who wouldn’t stop to find out more? Our intention was for the bricks to function like shiny coins noticed out of the corner of one’s eye, or twenty-dollar bills found on a sidewalk, turning a so-so day into a lucky and thoughtful one. Some people will come across the bricks as visitors to the city; others will come to regard the bricks as reliable old friends who age and weather with each winter that passes.

Installed Portland Brick Project bricks in the India Street neighborhood of Portland, Maine | Photo by Ayumi Horie

The largest cluster of bricks is installed at the intersection of India and Commercial Streets. At one time, India Street ended on a point of land that jutted out between two coves, but in the 1850s, the coves were filled in to accommodate rail lines, and Commercial Street was constructed. Long ago immigrants disembarked from ships docked in the harbor, and walked up India Street; today, this spot serves as a gateway to the city for the thousands of visitors from cruise ships every summer.

The bricks are numbered, with the first one reading, “All of these spots are on Wabanaki land,” a pivotal and too-often-forgotten fact about whose place this first was. Given all the recent political jockeying around issues concerning immigrants and refugees, we rarely look back far enough in our country’s history to see the shakiness of our own entitlement to citizenship.

All the other phrases begin with, “On this spot in . . .” or “On this spot every. . .” This introductory phrase sits perpendicular to the rest of the sentence and to the building fronts, so that the words can be caught from either direction. It’s no coincidence that the second numbered brick reads, “On this spot, every year, Ghassan Hassoon celebrates becoming a U.S. citizen #newmainer.” We live on layers and layers of history. Through this project, we underscore the diversity of Portland and how meaningful this neighborhood is to all the individuals and groups of people who have lived here for more than four hundred years.

We hope the Portland Brick Project will be reimagined and replicated in other cities as anti-monumental monuments to everyday citizens. As a potter, I feel that the transformation of clay to brick adds a crucial layer of complexity to the project. The humor, poignancy, and specificity of the stories make it successful and highlight what we love about our city.

Installed Portland Brick Project bricks in the India Street neighborhood of Portland, Maine | Photo by Ayumi Horie

This article originally ran in Studio Potter, Vol. 44, No. 2, Summer/Fall 2016, “Function/Architecture”, a publication dedicated to connecting potters and strengthening the dialogue within the pottery community.