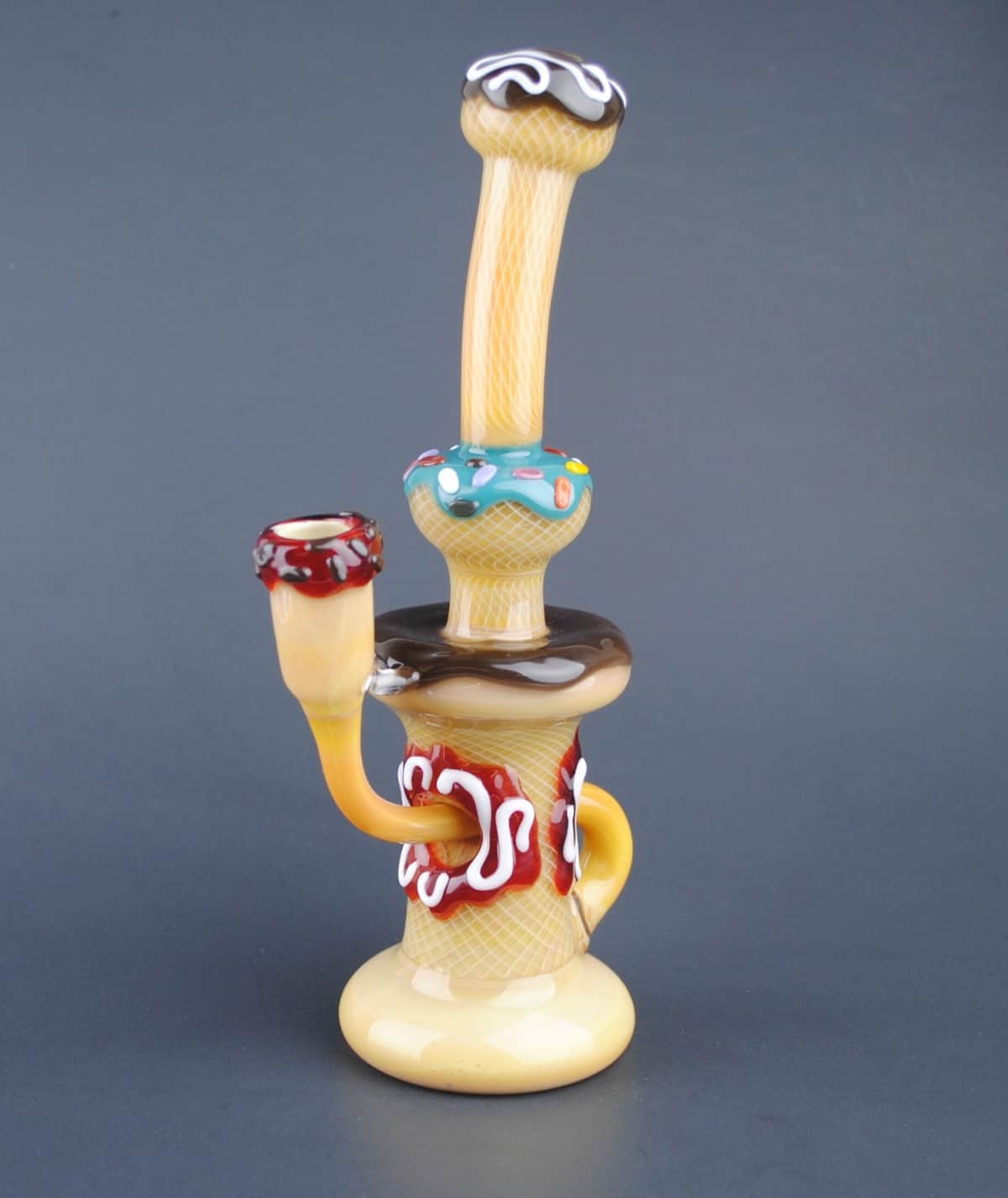

Burlington glassblower Charley Reynolds makes colorful high-end bongs equally suitable for smoke shops and galleries.

Charley Reynolds makes some serious bongs. The Burlington, Vermont glassblower crafts pipes of varied colors and forms with such virtuosity it’s hard to decide if his work would be better suited for getting people high out of their minds or sitting in the pristine displays of an art gallery. He’s a testament to the value of following your passion: A two-week glassblowing internship ignited his interest in 2006 while he attended boarding school, and today he makes a living selling his smokeware.

Pipe-making’s countercultural nature kept discussions with his family stiff in the early days. “Being a 16-year-old, it’s a pretty difficult question to ask your mom ‘Can I make pipes?’” Reynolds says in retrospect. “For many years we really didn’t talk about what I was making.” He gained some major experience during an eight month stint at The Bern Gallery after starting a biology degree at the University of Vermont. He took a year off from school to hone his craft and rented a room above Nectar’s, the infamous bar in Burlington where Phish first played.

Since January 2013, he’s been glassblowing full-time. He took a four and half month period to travel and learn the industry landscape, sometimes sleeping in his Jetta station wagon, sometimes crashing with bong-making confidants. His tour took him from Vermont to Maine, Massachusetts, and New York (a glass studio in the basement of a major Manhattan apartment building stands out), and continued to New Jersey, North Carolina, and Florida.

Photo courtesy of Charley Reynolds

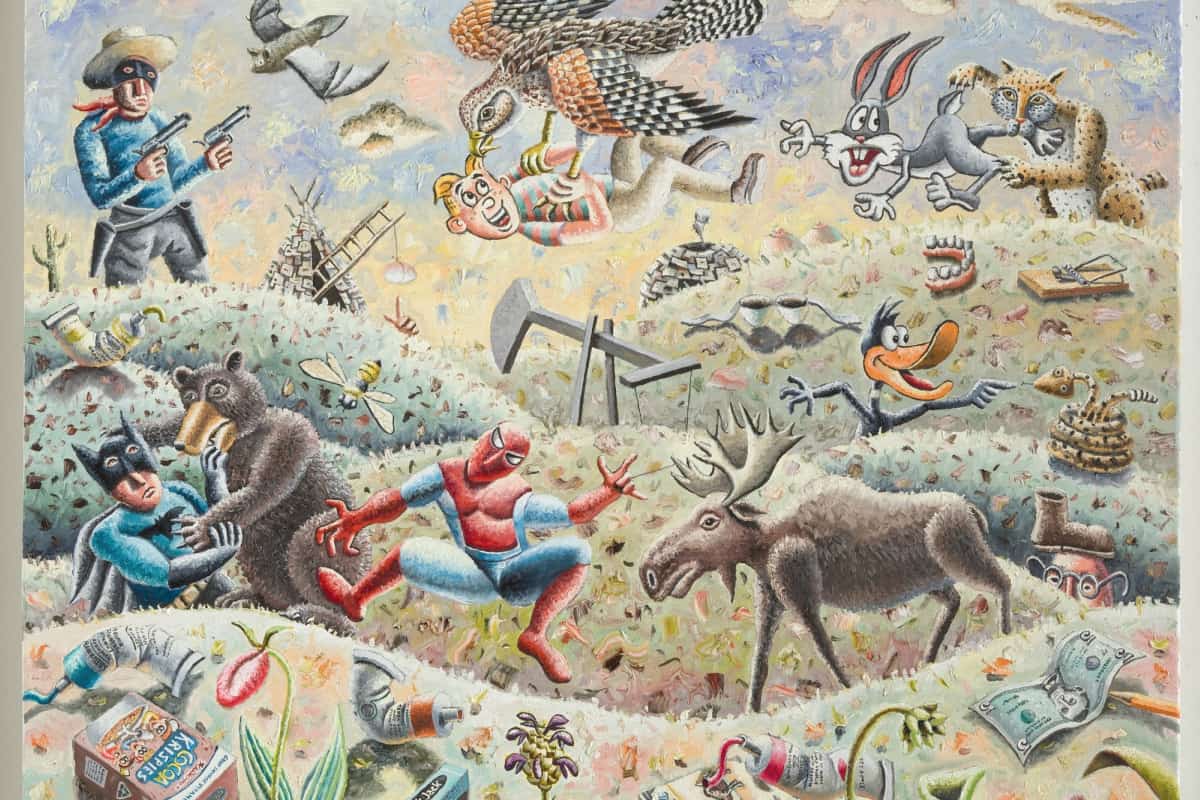

A workhorse mentality and desire to stay out of his comfort zone led Reynolds to develop his signature “plaidicello,” a reference to an Italian glass technique called the Reticello. He uses glass made with two percent depleted uranium, creating unique plaid patterns that come alive under a blacklight. “If anyone sees it, they’ll say that’s a Charley Reynolds piece,” he says. “If anyone tries to copy it, a lot people who are customers will actually defend me and contact them and tell them that they’re copying my work.”

Steady orders keep Reynolds making a lot of the same designs regularly, which can be tiresome. “It easily becomes a monotonous job where every day you make the exact same thing in the same style, and maybe all you do is change the color. Spending eight hours or so doing something like that drains your spirit. I think that’s why one of the most important things you can do in glass or any style of art is experiment.” Some of his new ideas include embedding tree patterns or the Vermont skyline in glass.

Collaboration between Reynolds and KGB Glass. Image courtesy of Charley Reynolds

Reynolds has built a sturdy pipe-making and selling network and a near 7,500-strong following on Instagram, where he conducts most of his business. “It’s the closest thing to a gallery that’s right on your phone,” he says. Putting his work on view in the vastness of social media has proven its worth. By 2016, he could sell a bong for $1,000 to $1,400 retail. Now some of his pieces pull $2,500 from store shelves. He sells his work all over New England and across the country, and recently received an inquiry from a smoke shop he admires in the United Kingdom.

Relationship-building remains a huge boost for Reynolds’ career. “The more traveling you do, the more shops you get to know, all the sudden a shop will see your work and say, ‘I’ve never seen it before, I love your idea, how can I get some?’”