Bath, Maine, artist Dozier Bell tunes into her individual voice to paint climate change through the crosshairs.

The dark, depopulated landscape paintings of Dozier Bell have earned her a reputation as an elegist, but her work and her ideas are far more unorthodox than that. For the past eight years, Bell has been mining the landscape around Bath, Maine, to see “how non-traditional I could make a traditional landscape look.” The majority of her pieces show natural scenes, but she never paints outside. “I like painting from memory because I like using that filter,” she says. “It’s a back and forth between being outdoors and the studio routine.”

A descendant of farmers, Bell keeps bees, hikes, and kayaks regularly to discover new visual details. “I pick through literature the same way I pick through the landscape for what I can use.” For example, “in recent years I’ve been doing drawings and paintings of trees which I haven’t done before. I have a sense impression of what looking up into a pine tree might look like but I can’t always bring to mind the exact pattern of light and dark so I go out.”

Outcrop Flock, by Dozier Bell

After earning a B.A. in philosophy from Smith College, Bell studied under Neil Welliver at the University of Pennsylvania. She took two things from him that still inform her practice: “the necessity of tuning into one’s individual voice, and the importance of just putting in the hours in the studio that it takes to find that voice.” If you log the hours, Bell says, “you end up with a body of work.”

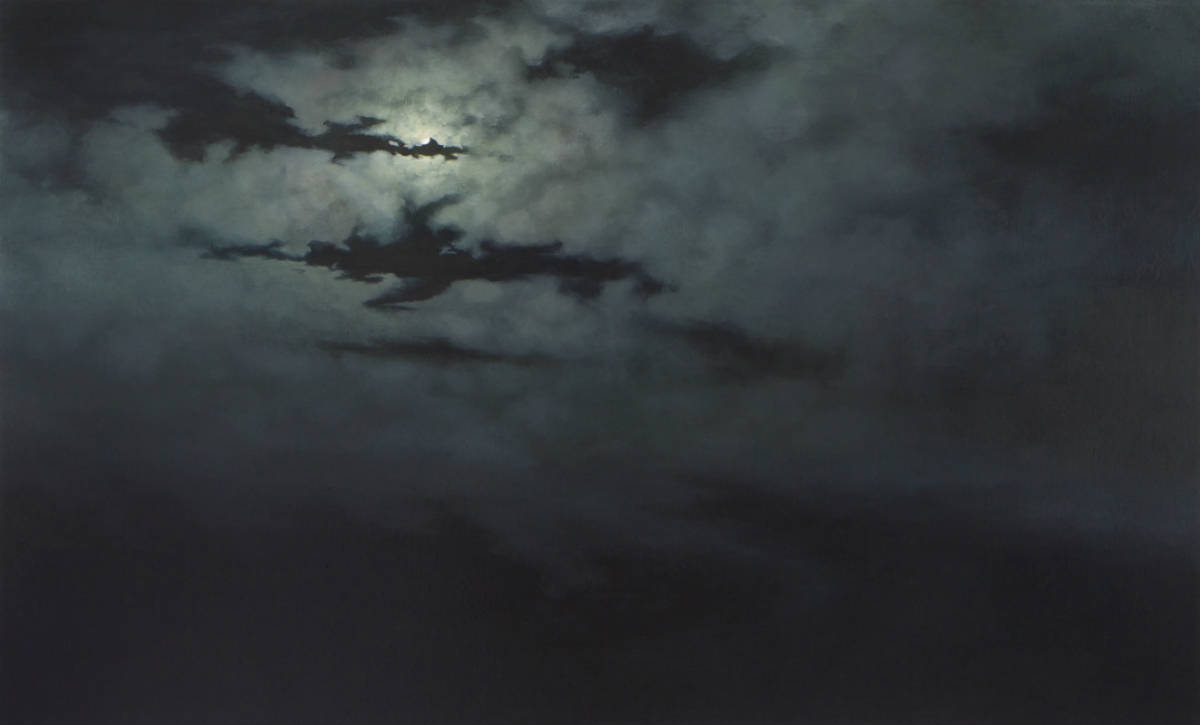

Bell’s own body of work reveals an abiding interest in German Romanticism. Recently, the threat of climate change has plunged her back into German stories where “the landscape, animals, plants, and the weather were characters in the drama,” and as such, capable of “retribution, spiritual solace, or some kind of divine purpose.” This concept of nature has “an inescapable moral dimension” that helps her to reckon with an increasingly unpredictable environment.

22:00, 2014. acrylic on linen, 30” x 50”, by Dozier Bell

While in Germany on a Fulbright Scholarship, Bell took stock of the landscape WWII had marked and also witnessed a new kind of religious questing. While volunteering at a local Lutheran Church she met East Germans who were beginning to explore religion again after reunification. “I saw these parallels between the fighting and finding devices like sonar and radar that were developed during the war, and the spiritual finding devices or process people were going through with religious training.” The conflation of these two very different kinds of human searching still moves her today.

Inspired as they are, Bell’s landscapes are omniscient and therefore slightly ominous. A number of her seascapes feature the geometric lines of remote sensing weapons, as if the viewer were training a rifle on the waves. The artist insists however that the lines of a viewfinder don’t always impend violence: “they could be weapon sights, they could be the crosses on a Réseau plate used in photographing an unfamiliar area like the surface of the moon…” With her paintings, Bell gathers together weapons, radar, and religious longing with the one sense they all share: sight.