Artist Erin Woodbrey explores the maternal functions of made objects in her newest solo exhibit at Gaa Gallery in Provincetown.

All of Erin Woodbrey’s work stems from a curiosity, bewilderment, and deeply felt confusion about the world. Using a sort of image and material-based existential inquiry, she often finds herself asking, how did we get here?

Woodbrey’s most recent exhibit, Time Mothers—on display at the Gaa Gallery in Provincetown through October 8th, is no exception. “With Time Mothers I wanted to explore the significance of objects,” Woodbrey says. “I was looking at objects as time-based reliquaries, and documents of lived experience, held, worn, used, and re-purposed.”

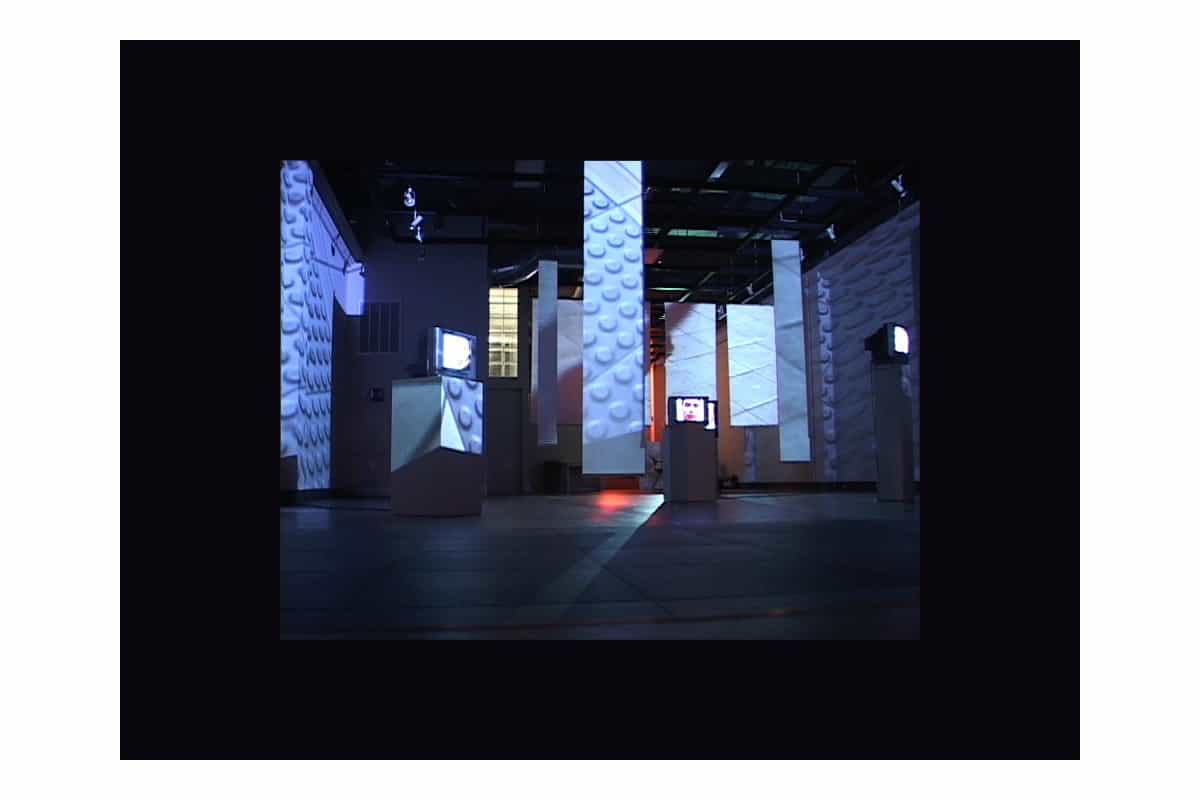

The objects ranged from books, tables, projectors, images, chairs, eggs, and clothing, to art objects and public spaces. In Time Mothers, Woodbrey explores how we interact and learn from these objects in everyday life, both private and public, as well as the unseen and physical part that happens silently, through accumulation, interaction, and lived experience.

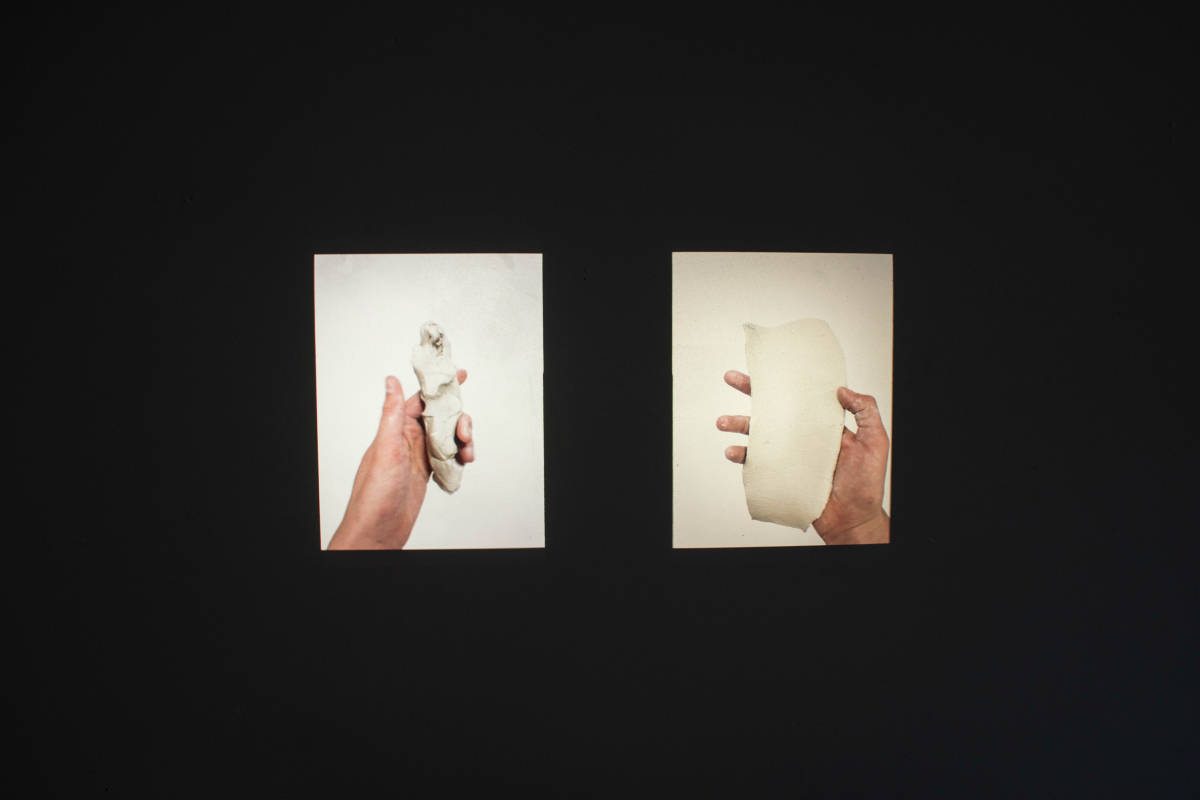

I’ll Be Your Mirror, 2017, color slides with slide projector on plywood stands, variable dimensions. Photo courtesy of the artist.

“There’s something profoundly esoteric about objects, especially things that have been around for awhile or have history. They sort of take on another life outside of their initial and intended purpose,” Woodbrey says. “I always wonder about where things came from and how they’re made.” In this way, the show is also an inquiry into the origin of objects and the act of creating, which begs the question: What drives the impulse to create?

Woodbrey asks these questions and many more through Time Mothers, the title of which is a sort of a poem in itself. It’s a call to action to think about our mothers more, think about the things that care for us, our well being, and betterment. “If we thought of all our mother figures more, maybe we would be less destructive, more supportive, and make better decisions, either in honor or protest of such a figure,” says Woodbrey.

God Mothers, 2017, plaster, paper, books, chair and plywood platform, variable dimensions. Photo courtesy of the artist.

The inspiration for Time Mothers came in part from a sculpture Woodbrey found in a park of a woman holding the head of a horse-like creature. The figure and the animal were created of stone and cast concrete but the woman’s head was missing and in its place was a piece of bronze rebar. “In the absence of that I thought she needed a name. So I called her Time Mother,” Woodbrey says. “The park is a very visible public space, in close proximity to a highway, a train, and a bikeway, but overall the space is a place on the way to another place. I see her as a silent overseer to all of this.” A large scale image of this sculpture serves as the focal piece for the exhibit, which also features a series of ceramic pieces, video stills, and sculptures created using everyday objects (objects that Woodbrey has learned from in the past).

Fragment (Weave), 2017, porcelain, 22 1/2 x 7 x 2 3/4 in. Photo courtesy of the artist.

“Spaces and things not only reveal and tell stories about our history, but they have the power to form our lived experience,” Woodbrey says. “Our interactions with objects and nature illuminate a certain causality of our thinking, accumulation of actions, and maybe even, if we choose to listen and look closely, what eventualities may exist ahead.”