New England’s last living archive of synthesizers and electronic instruments is online and part of a long, somewhat tragic history.

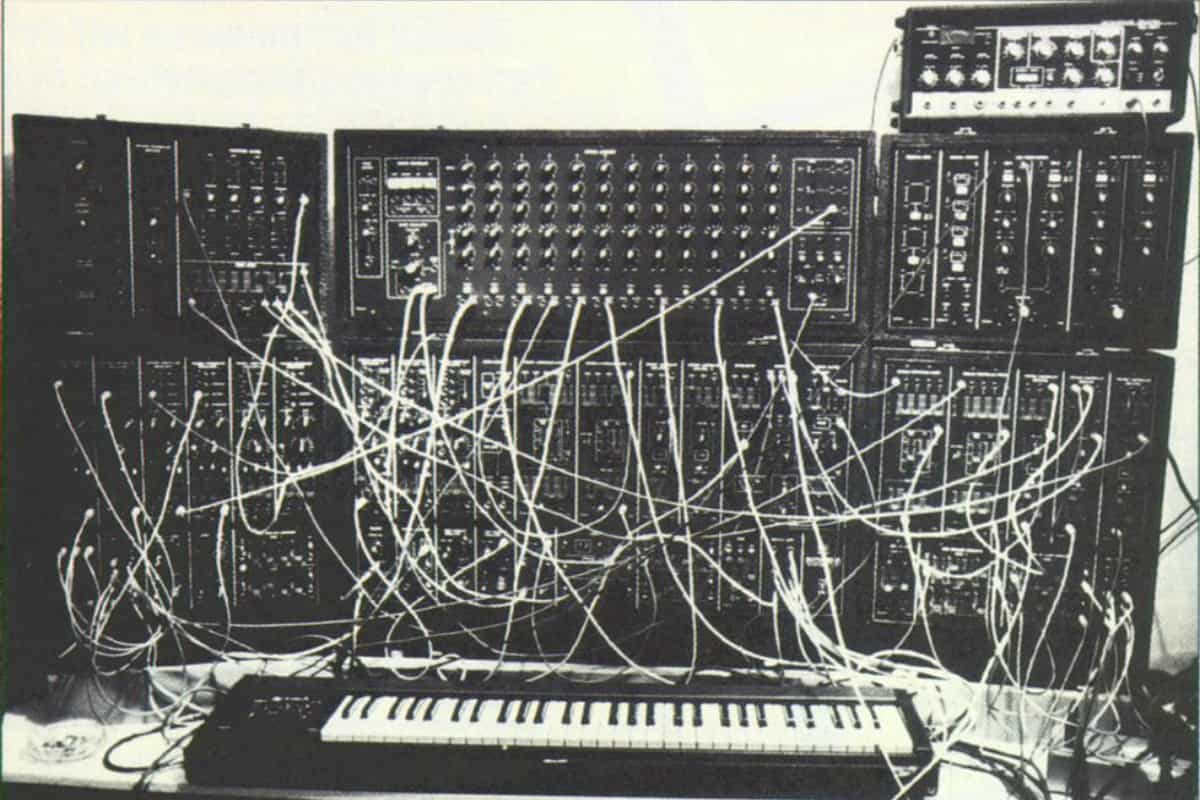

Our region is home to some of the world’s most dedicated synthesizer archivists, people who’ve spent their lives documenting this built analog circuitry of sound. Like the intricate mazes of inputs and connections hidden inside these electronic instruments, New England also has a deep, complex, and somewhat tragic history with synthesizers.

You can’t accurately or truthfully discuss the history of synth archiving and documentation in New England without mentioning the region’s original synth nerd-god, David Wilson. Wilson dedicated two floors of his home in Nashua, New Hampshire to curating, cataloging, and repairing vintage synthesizers. He opened his home to the public, allowing synth obsessives from all over unbridled access to his machines. Wilson would personally set up these instruments, and allow museum-goers the unique opportunity to examine and even play most of his synths. To the shock and sadness of many, Wilson passed away too soon in 2010. His close friends, family, and casual museum patrons describe him as genial, a bit eccentric, and democratic with his appreciation for all people and synths, not just the “important” ones.

David Wilson in his home | Photo courtesy Matrix Synth

Years after Wilson’s passing, his collection remains in limbo. However, there is a resource where some of his synthesizers can be seen and appreciated: Synthmuseum.com, a Boston-based operation that offers “a centralized, organized, and authoritative resource for information about vintage electronic musical instruments.”

The online synth museum is the brainchild of Paula Chase and Jay Williston, who, in 1996, after visiting David Wilson at his in-home museum, decided that the internet would be a great place for a synthesizer archive fueled by user-submitted content. “There wasn’t one place where you could see synthesizers and find out about their features, find out about what existed and when it existed, what it looked like and who played it,” says Williston “This started with us going to visit Dave’s museum. We thought, ‘Oh, wouldn’t it be great to put his museum in a nice building?’ But then we thought, ‘We can’t do that, it’s not our place.’ But we figured we could take his synths, and synths from everywhere, and put them online.

Moog Sonic Six | Photo by Kevin Lightner

“When we started this,” he continues, “we just asked people to send us pictures of synthesizers, brochures, and manuals. It’s basically getting everything you want to know about vintage synthesizers in one resource.”

Today, Williston is the only founder who continues the highly labor-intensive process of updating the website. Since the beginning, Williston and the founders hand-typed everything from manuals, magazine descriptions, or brochures, and still receive corrections, comments, and feedback from folks perusing the site. The website is clearly from the mid-to-late 1990s, and Williston isn’t bashful about pointing that out. For people poking around the site, its dated look lends an extra layer of meaning and congruity to the archive. After all, wouldn’t it be sort of weird to seamlessly click through a collection of late 1980s electronic instruments using a sleek, futuristic, Square-Space-like template?

![[This] "Polyvox belonged to a trance-ambient band that played on same stage as we did in a festival last summer. In fact, it wasn't really their's either, they had borrowed it from a friend who got it from the janitor at a russian school.... The band called themselves 'Lhix', and are a local but highly competent young band from Umea, Sweden.... The picture was taken by me." ----Patrik Eriksson, Umea Sweden | Description from Synthmuseum.com | Photo by Patrik Eriksson](https://thetakemagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Polyvox.jpg)

[This] “Polyvox belonged to a trance-ambient band that played on same stage as we did in a festival last summer. In fact, it wasn’t really their’s either, they had borrowed it from a friend who got it from the janitor at a Russian school…. The band called themselves ‘Lhix’, and are a local but highly competent young band from Umea, Sweden….The picture was taken by me.” – Patrik Eriksson, Umea Sweden | Description from Synthmuseum.com | Photo by Patrik Eriksson

Perhaps someday David Hillel Wilson’s collection will be open to the public again, and perhaps someday Jay Williston will document and list every synthesizer ever made. Until then, we have Synthmuseum.com, and our piqued curiosity about what wild electronic reverberations lived in Wilson’s two floors in Nashua, New Hampshire.