Connecticut’s Vinegar Syndrome saves the grittiest exploitation flicks from oblivion, one cult movie at a time.

From the outside, the headquarters of Vinegar Syndrome in the North End of Bridgeport, Connecticut, could easily be passed by without second thought—it would seem like just another nondescript industrial building. Inside, however, is an astonishing environment where film preservation and restoration takes place.

But not just any films. Beginning with its first release in 2012 of The Lost Films of Herschell Gordon Lewis, the company has restored and re-released cult films and long-lost gems of the grindhouse and drive-in eras from the 1960s through the 1980s. The company’s mix of horror and exploitation titles—Count Dracula’s Greatest Love, Psychic Killer, In Search of Bigfoot—may be a far cry from the more genteel classics that one associates with film restoration, but without Vinegar Syndrome these gritty and outlandish productions might disappear forever.

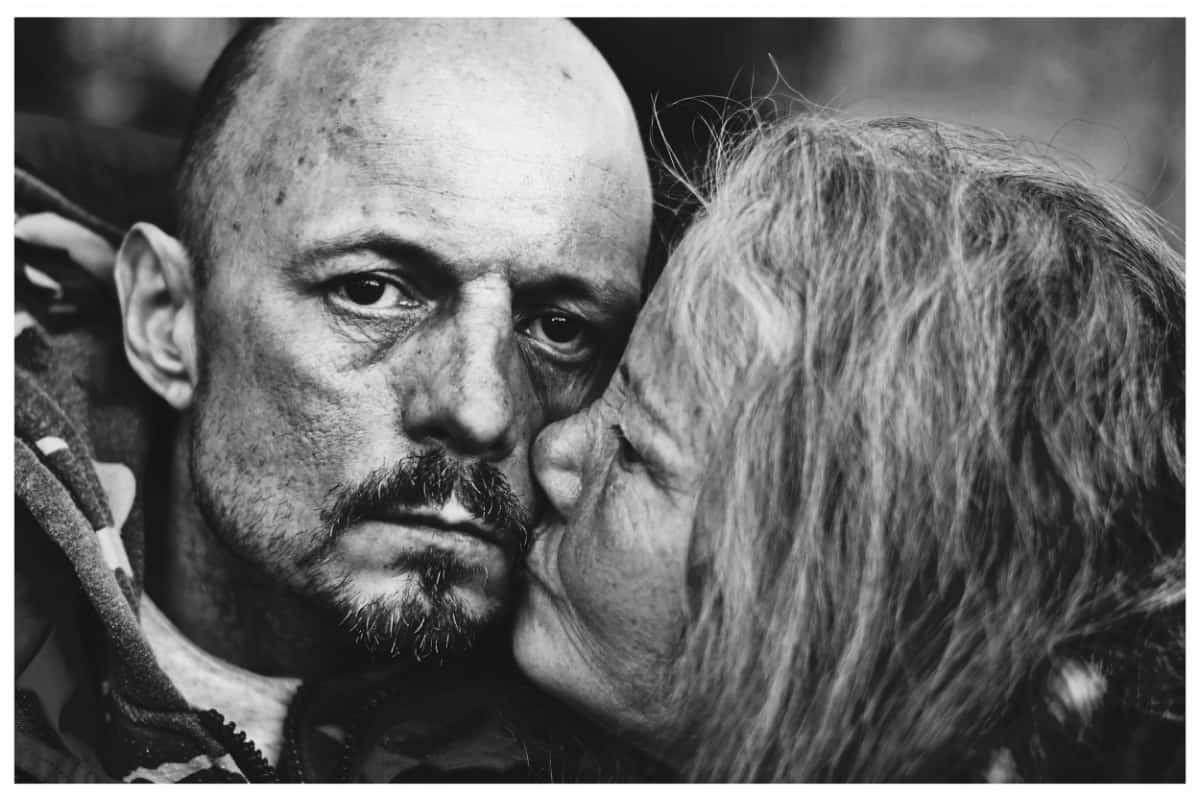

Vinegar Syndrome film restoration, Bridgeport Connecticut

“The exploitation genre in general is the second most amount of lost films, aside from the silent era,” says Brandon Upson, restoration artist at Vinegar Syndrome. And, indeed, the company’s name is a reminder of the fragility of film as a medium: “vinegar syndrome” refers to the rancid odor that occurs in the degradation of acetate film base.

“We’ve digitally preserved about 500 films in the past five years,” says Ryan Emerson, the company’s co-founder and director of production. “In our film archives, we have thousands of elements. And we own the rights to 300 to 400 feature films.”

Tracking down these films is no mean feat: in many cases, the original production companies and distributors went out of business decades ago, and the filmmakers may not even have prints of their works. Ralph Stevens, the company’s business development director, says that Vinegar Syndrome often scoops up films that would otherwise be thrown in the garbage dumpster.

“Labs that close down and clear out their inventory,” Stevens says. “We’ve found films in storage spaces where people are trying to get rid of stuff. We’ve also dealt with companies that foreclosed on storage spaces that have films, as well as private collectors. And films turn up in old movie theater basements, auctions, and on eBay.”

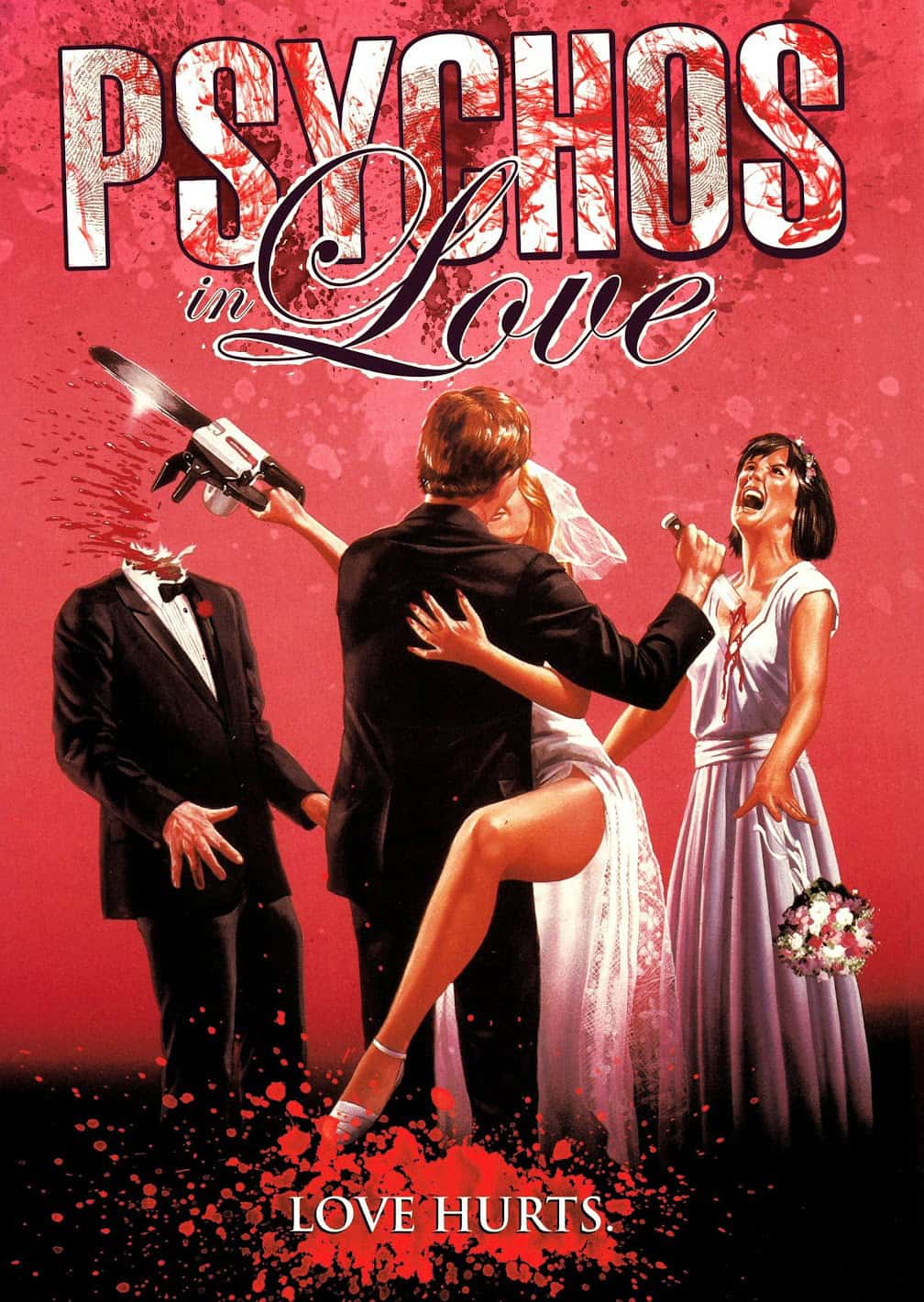

Psychos in Love film poster, courtesy of Vinegar Syndrome

The length of time it takes to digitally restore a surviving 35mm or 16mm film print or negative depends on the element, Upson says. “If we have the camera negative, we still want to take a good amount of time on it. A digital cleanup could take 40 to 80 hours of sit-down work if the negative is perfectly clean,” he says. “We’re looking for scratches and dirt that accrues on film. We have alcohol cleaners and sonic cleaners, and now, with digital tools at our disposable, that really helps in getting the dirt off.”

Vinegar Syndrome’s 50,000-square-foot facility serves multiple purposes for restoration, storage, and shipment. The internal temperature in the storage section is noticeably cooler than the rest of the building, as heat and humidity can have lethal effects on delicate film elements, and the facility is designed to aid in this process: in prior years, it served as a fur storage vault and a vegetable distribution center.

The company puts its restored works into retail channels via DVD and Blu-ray. Upcoming releases include Melvin van Peebles’ groundbreaking 1971 blaxploitation landmark Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song, the 1986 sex comedy, My Chauffeur, and the Connecticut-lensed 1987 underground horror/comedy cult favorite Psychos in Love. In June, the company opened a retail unit that sells its DVDs and Blu-rays along with movie memorabilia and vintage vinyl albums. Emerson says the store, which is open on weekends, helps to connect the company with its neighborhood and with local like-minded film buffs.“In our first weekend,” he says, “we brought people here from all over Connecticut who have not been in Bridgeport in decades.”