In a new Craft in America episode, Vermont woodworker Michelle Holzapfel talks about her impulse to carve her way to fine art.

Michelle Holzapfel acknowledges that she has some talent for whittling wood, but she credits as much of her artistic success to sheer chance. “You go along almost following your nose, following some feeling that you can’t even put words to,” she says in the latest episode of the PBS series Craft in America. “And that aspect of things cannot be overlooked. It’s very important to take your chances.”

The new “Nature” episode of the series, which celebrates handcrafted creativity across the country, included Holzapfel among five artists who pull their inspiration, materials, and medium from the natural world. Holzapfel embraces every knot in the pine, every twist of burlwood, every fissure that she works into a design.

Her work is technically astute yet thematically whimsical. Her trompe l’oeil pieces include a remarkable rendition of a knitting basket, detailed down to every wrap of yarn, and book ends that themselves look like stacks of books, one with a Raggedy Ann doll seated atop. Some of her vases and bowls hold intricate carvings of leaves, faces, coiled snakes, and even a “knitted” wooden sweater. In other sculptures, such as an apple with its stem still attached to a branch with leaves, the wood appears as sleek and impenetrable as marble.

Michelle Holzapfel, Vermont Spoons

Holzapfel grew up in rural North Smithfield, Rhode Island, learning to make things by hand—from a fort of branches in the woods to clothing stitched with needle and thread. Her mother made dresses. Her father was a machinist who did carpentry and metal work. “As a kid, as long as I can remember being alive, I loved to manipulate my world,” Holzapfel says. “I just grew up sort of immersed in a culture of fixing things, making things.”

In high school, she tried printmaking, using tools to cut wood for block prints. “I discovered that I really liked the carving part better than the printing part.” For her first commissioned work, she whittled name plaques for neighbors to hang at their front doors.

Her family took regular trips to the Rhode Island School of Design in Providence to see shows and the museum. Today, the RISD museum collection includes her work, as does the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston; Yale University Art Gallery in New Haven, Connecticut; the Museum of Arts and Design in New York; and the Currier Museum in Manchester, New Hampshire.

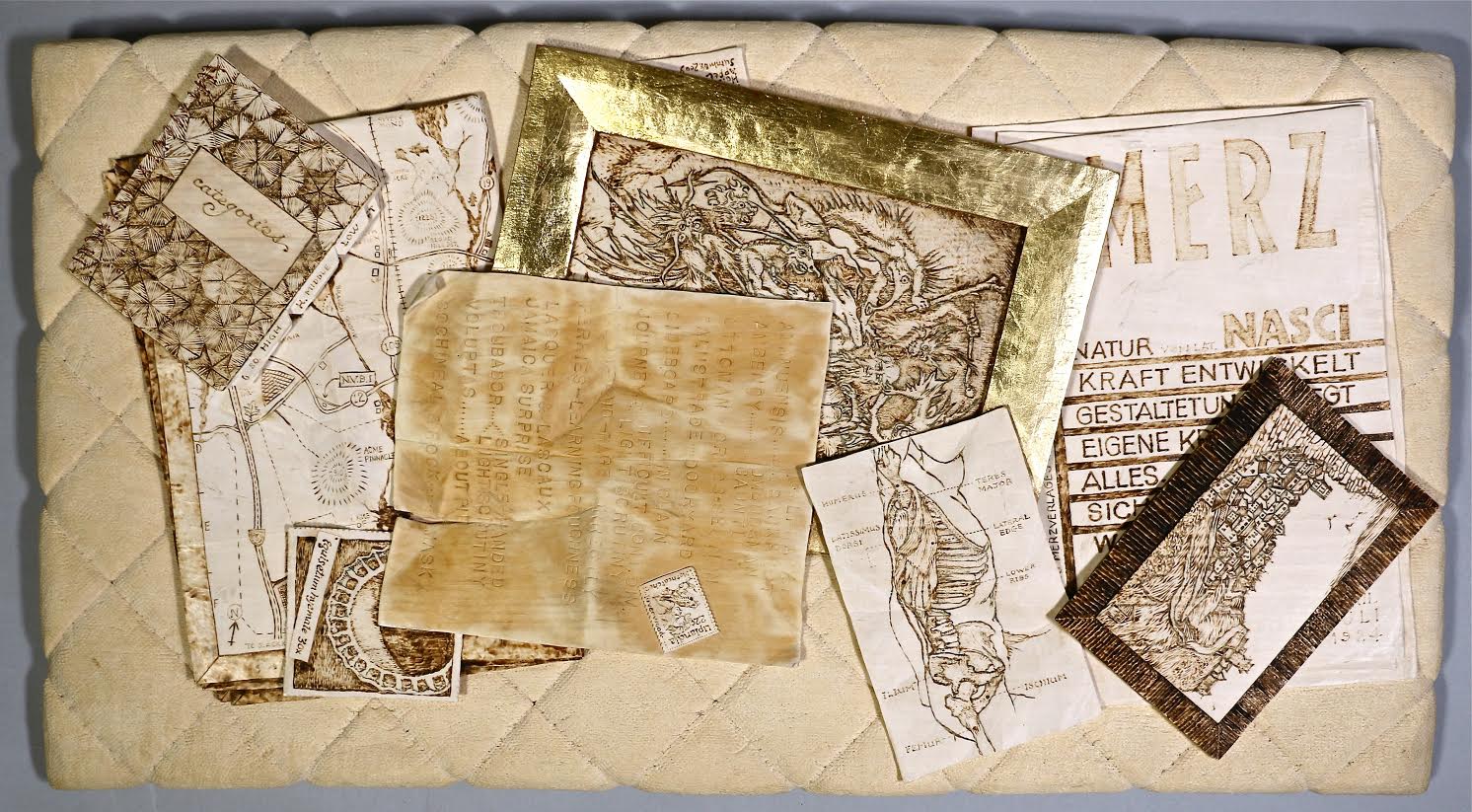

Michelle Holzapfel, Rage Correctly

Holzapfel came to Vermont to attend Marlboro College, where she met her husband, fellow woodworker David Holzapfel. They started selling their creations at craft shows and to travelers passing on Route 9 in the summer.

After their two sons were born, the Holzapfels realized that sending them to college and providing them health insurance required the financial anchor of a full-time job. David set aside woodworking and became an elementary school art teacher in Marlboro.

By the 1990s, galleries in New York, Atlanta, Los Angeles and Philadelphia had picked up Michelle’s work, fetching her prices upwards of $12,000 for a piece. After 30 years of relentless paring, her pace has slowed now, but she still sells to patrons and picks up commissions.

Yale University recently asked her to create the mace—a ceremonial staff representing each of its colleges—for a new residential college named for civil and women’s rights activist Pauli Murray. And this month, a show of Holzapfel’s work opens at The Gallery at Rhodes Arts Center at Northfield Mount Hermon prep school in Massachusetts.