Studio 860 inspires young hip-hop dancers and spawns new talent in the Hartford, Connecticut dance community.

This article originally ran in our November 2015 print issue.

When he was a little younger, Peter Reynolds worked in the mail room at the Hartford Steam Boiler building, one of the tallest office buildings in downtown Hartford, Connecticut, abutting I-91. He often worked solo at the end of the day, and he says that if you could have watched him, between organizing stacks of packages and envelopes, you might have seen him popping, locking, and vibrating, working on dance moves during the downtime at the end of his shift.

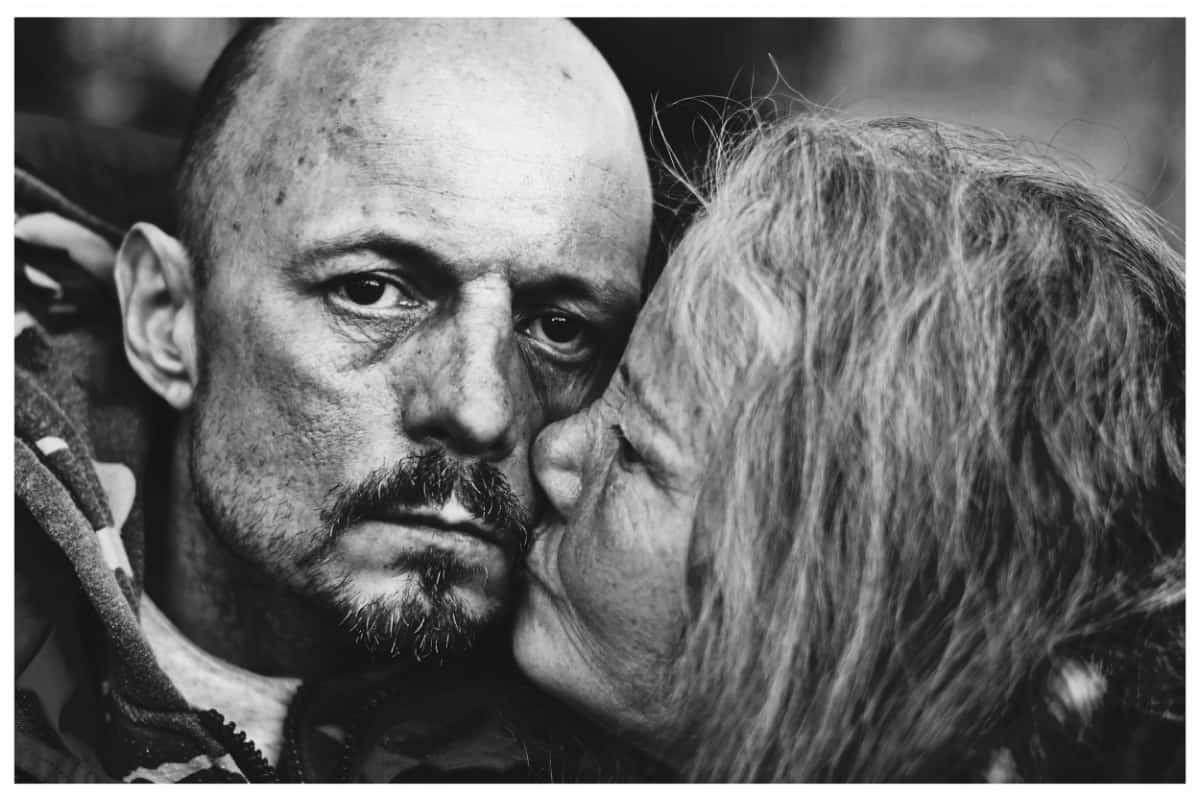

Peter Reynolds (left) and Jolet Creary grew up dancing in Hartford and founded Studio 860 in 2012.

“I was the last one to leave, so by five o’clock I was in there jamming out,” says Reynolds.

Reynolds, 31, also known as P-Boogie, is a dancer and an educator, and one of the co-founders of Studio 860, a dynamic studio that teaches young people the arts of hip-hop and street dance. Reynolds helped launch Studio 860 in 2012 with Jolet Creary, the artistic director, in Hartford’s Parkville neighborhood. The second-floor studio is in a converted mill complex, a few buildings up from Real Art Ways, an arts and performance space with a movie theater and gallery; just a block or so away from a new CTfastrak rapid transit station; and up the road from thriving Puerto Rican, Portuguese, and Brazilian communities.

The area code for most of Connecticut is 860, and, as the name suggests, those behind the studio take pride in its connection to the region and particularly in its Hartford roots. Reynolds and Creary, who both grew up in Hartford, have put a lot of themselves into the studio—pulling up carpets, scraping off glue, and making the floors ready for the stomping and sliding of dancers’ feet. Their lives have been transformed by dance, and they work to inspire transformation in the dancers they teach and share the stage with. Their instruction focuses on fitness, artistic expression, community, and self-possession.

Dashawn Davis is part of Studio 860’s teen competitive dance team, Elite 860.

Creary started dancing when she was a toddler, at the feet of her grandmother, who danced around the house and at practically any time. From there, Creary studied Caribbean dance traditions at Hartford’s venerable West Indian Social Club, a cultural hub in the city’s North End. Soon she was watching Nutcracker videos and taking ballet lessons as well. Videos of Michael Jackson and Paula Abdul left their mark too.

Reynolds had formative exposure to hip-hop dance as a kid at summer camp. “I had an instructor—his name was Tommy Hill, so even his name I thought was cool, because of Tommy Hilfiger,” he says. “And he was from England, so he also had an accent and everything. He was real cool.”

Reynolds remembers Hill demonstrating some moves as the two were up early one morning waiting for the day’s events to start. The counselor broke out some eye-catching tricks, isolating body parts and letting the movement ripple through his arms and shoulders like a visible energy current. “He had all these chains and bracelets on, and I remember him vibrating and ticking,” he recalls.

Street dance, hip-hop dance, contemporary African American vernacular dance—this genre has been steadily dominating mainstream American culture for decades now, maybe just slightly behind its musical counterpart. Think of the Fly Girls dance troupe from TV’s In Living Color or the 1990 documentary Paris Is Burning, about the largely gay and black New York City voguing scene that inspired Madonna. More recently, look to Rize, the 2005 documentary about the LA krumping scene, or to the high-profile status of Memphis jookin’ dancer Lil Buck, who has performed with Yo-Yo Ma, at a TEDx conference, and with the New York City Ballet. Or just watch hit shows like Dancing with the Stars or So You Think You Can Dance.

The increased prominence of dance means more people are interested in the subject, but it may also mean there’s a greater gap between pop culture representations and real-world connections. “Over the years, dance has become a lot more commercialized,” explains Creary, “but there’s still a lot of dance that hasn’t been seen on television in its fullest form. There’s been a lot of commercialization of hip-hop, and not just hip-hop, but also jazz, modern, ballet—everything—and even African dance.”

Creary teaches West African dance at Trinity College in Hartford. She is also the choreographer and artistic director of EQuilibrium Dance Theatre, Connecticut’s first hip-hop dance company. Though it’s only three years old, Studio 860 has evolved into a spawning ground for regional dance talent, a hub for traveling dance instructors and performers, and a supportive community of creative young people.

In late summer, student dancers gathered at the studio before heading down to an open-air jazz series at Bushnell Park, the majestic park abutting the state capitol at Hartford’s center, to raise funds for a trip to Atlanta for World of Dance, an international dance competition. Twenty-two student dancers performed on the team. Sixteen-year-old Jasmine McPherson of Hartford was one of the competing dancers, and one of the fund-raisers. The 11th grader, who’s been studying ballet since she was five, plans on pursuing a career in dance. McPherson appreciates the perspective she gets at Studio 860, the ways in which Creary and Reynolds and other instructors orient dance within culture, and how the studio is a model of a viable livelihood within the arts.

Twenty-two of Studio 860’s student dancers competed in the international dance competition World of Dance in Atlanta in August.

“It’s not that we’re just taking a class to dance; we also do a history lesson on how things started and how things progress,” says McPherson. “I’m not just learning about dance, I’m learning about the business aspect, about how you run your own studio. What it takes to fundraise, what it takes to get a business off the ground.”

Those bits of history might come in the form of a mini-lecture from Creary on the origins of some of the traditions taught at the studio, but it might also come in the form of firsthand exposure to guest artists who are foundational dancers within the genre. “Because hip-hop is so young, in reality a lot of the people that invented the style are still around,” says Creary. “So it’s easier for us to access it, to actually get some type of oral history.”

History aside, students at Studio 860 are learning serious dance. Rooted in street dance and hip-hop, the movements demonstrate a grace, control, and creativity that helps explain why this art form is captivating new audiences. Hip-hop dance, like the music, pulls from unexpected sources. Hip-hop music was built on a foundation of funk and soul rhythms, deconstructed—chopped into pieces and reconfigured with added elements. Everything from jazz, classical, film soundtracks, rock, and found sounds got stitched in, with percussive rapping in complex phrasing layered over the top. It’s an avant-garde collage of sly and high-contrast reappropriations.

The same is true of the dance. So many of the genre’s eye-grabbing moves involve a marked juxtaposition of near-stationary body parts with other body parts isolated in extreme motion, or a tendency to cultivate a series of dramatic slow-motion movements jammed against a few fierce and rapid articulations: a jutting of the head, a pivot of wrists and hands, a quick sideways bend of the knees and ankles to approximate a kind of broken-boned slump. Other moves seem to depict powerful surges of energy coursing through the body, making it ripple and bulge at the edge of what can be contained by muscle, bone, and skin. And virtuoso variations on timeless moves like the moonwalk, the wave, and the robot can still astonish audiences.

Though it’s only three years old, Studio 860 has evolved into a spawning ground for regional dance talent.

Creary and Reynolds point out that hip-hop dance uses a vocabulary of movements plucked from sources outside of dance. Elements inspired by silent films, mime, sci-fi, martial arts, animation, and stop-motion flipbooks have all worked their way onto the dance floor.

Beyond the physical skills, the sense of cultural history, and the insight into arts administration, many of the students at Studio 860 experience something deeper and more basic, notes Creary.

“A lot of our students are getting a sense of self-confidence out of this,” she says. “It’s definitely therapeutic. We have some people that come in here . . . whatever’s going on outside, when they come in here they feel an acceptance. We have a lot of people that say this is their family. There’s a sense of belonging. Even if they’re not going to become professional dancers, they’re given that opportunity to perform. They’re given that opportunity to be seen being taken out of whatever their environment is. I always say that you can do whatever you want when you’re dancing. It’s a crazy high that you get from dancing.”