Sound artist and musician Halsey Burgund is listening to what we say, hoping to help bridge the political divide in America.

Halsey Burgund picked a good time to explore the right/left political divide in American life. We could use a path that can make sense of how ideological polarities might intersect. Burgund is a Boston-based installation artist, software developer, and musician. All three of his pursuits share a preoccupation with harnessing the creative and emotional force of the sound of human speech and putting it to new uses.

Radio Right Left is a project that Burgund launched on his site in January. With volunteers from both ends of the political spectrum anonymously contributing recorded statements addressing our collective future and where they see themselves in it, Burgund works to bridge a divide, allowing everyone the opportunity to take in the views from the other side, possibly fostering some much-needed understanding. That’s the hope.

“The point of the piece is to try to pop the filter bubble, and not just dismiss people who don’t agree with you. I didn’t want this to be about specific issues,” says Burgund. “I feel like there are certain contingents within the political perspective that are trying to divide us, because a divided populace is more easy to control. Simply dismissing other people because they disagree with you on one issue is, I think, counterproductive to the health of the country.”

Using location-based information from smartphones and an open-source application that allows users to upload their commentary, Burgund aims to create a map of the U.S. that might not conform to our somewhat simplified Red State/Blue State conception of things. What comes through is the sense of anxiety that pervades the country. Or perhaps the anxiety of a particular audience that is inclined to participate in a journalistic audio-art project. The piece uses randomized pieces of these voices, floating in and out against Burgund’s ambient-leaning music that hovers and blooms along with the scraps of speech.

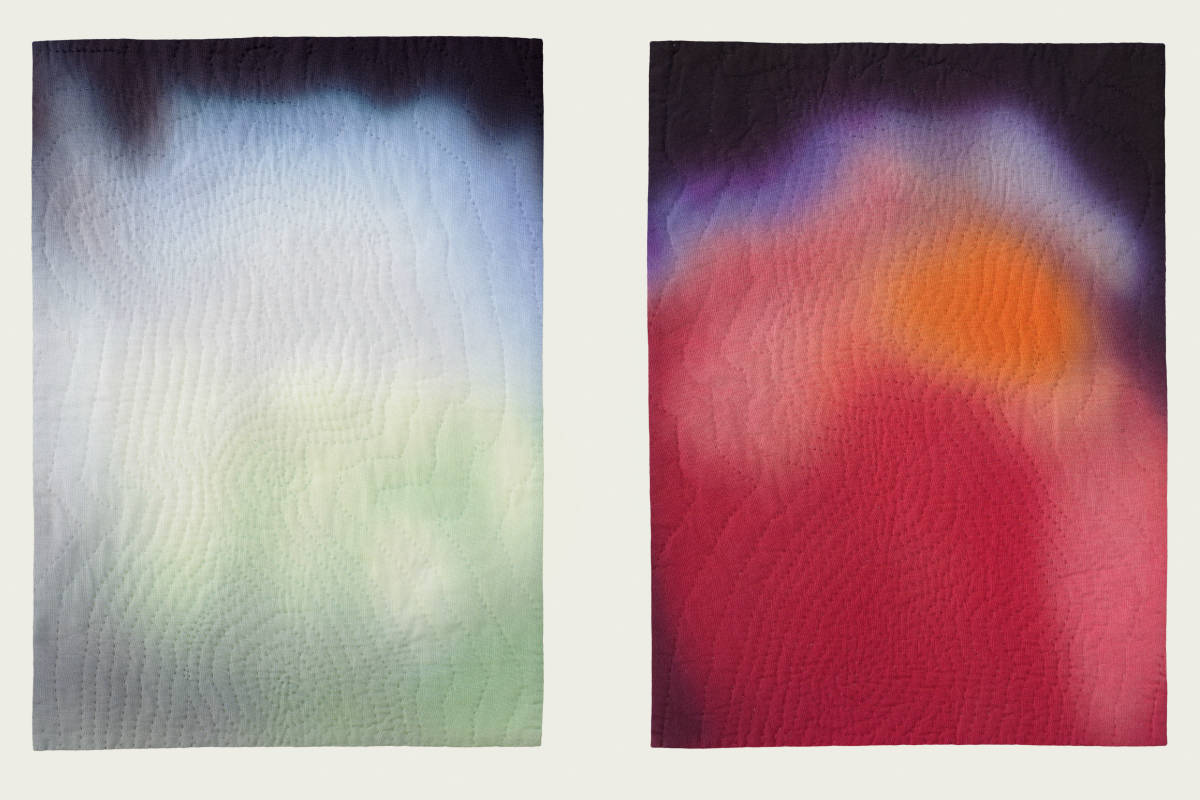

Bog People is one of Burgund’s site-specific sound installations

Burgund’s work isn’t always so current-events-related. He’s used geo-tagging technology in projects—such as Tributaries, made in Tyneside in the north of England—that invite volunteers to contribute audio pertaining to a specific location. This then gets uploaded and can be accessed by users when they’re on that same spot. It’s a bit like having the power to turn the whole world into an interactive audio museum tour, with evocative cinematic music to go along with it. Burgund has also created projects like Bog People, about a decommissioned cranberry bog in Plymouth, Massachusetts. Gathering the voices of people who use, work on, or visit the land, Burgund, with the help of the randomizing software, gathers together and re-presents a sound story about the location and the layers of individuals who it has meaning for, and who shape it or are shaped by it.

These aren’t just spoken documentary fragments. The attraction to the subtleties, textures, distinctive phrasing, tonality, and emotional resonance of human speech is something that has fascinated the 43-year-old artist for years. Burgund’s first venture into blending the musicality of speech with instrumentation involved a recording of his parents reading one of his poems. Since then, he’s also made music that uses recorded voices, sometimes from people answering questions about a subject (“What would life be life with no oceans?”), and sometimes with random zany fragments of speech—complete with bursts of laughter, pauses, or peculiar stresses—gathered from volunteers contributing to his project. The voices are saying things that listeners can generally understand, but Burgund seems as interested in the rhythmic dash and flow of the sound as the words being uttered. The work of minimalist composers like Steve Reich and Alvin Lucier come to mind in some of the ways Burgund approaches speech as a form of musical material. His music also evokes comparisons to the landmark Brian Eno/David Byrne album My Life In the Bush of Ghosts, which gathered archival bits of speech from preachers and newscasters, using the voices as a component in jittery but funky post-punk songs.

“The voice has multiple levels of content and only one of them—a very small one of them in my mind—is semantics,” Burgund says. “To me, there’s so much more information that one can get.”

Think of Pokemon Go, a huge event in the mobile gaming world last year, and imagine an artist with a fondness for narrative, speech, and ethereal music taking the same positioning technology to make art that is interactive, archival, and personal. Making spectators into contributors and enticing them with the thrill of unlocking and accessing facets of a piece of art by moving through space, while they take in the setting and history and give something back of themselves, gives you a sense of what Burgund is up to.